Correspondence 3.2

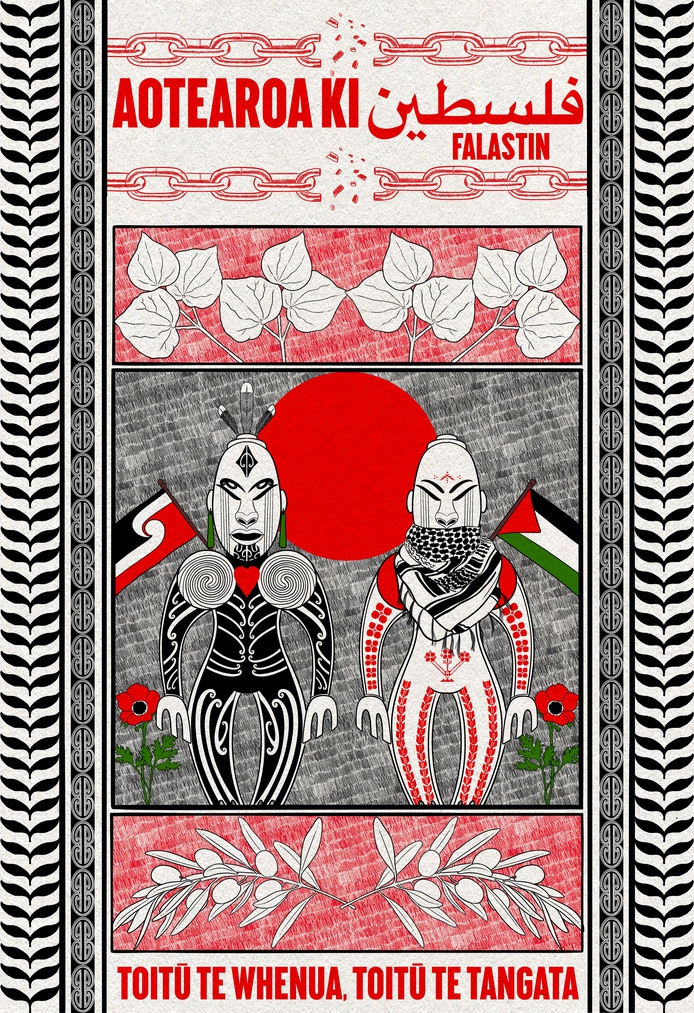

Correspondence 3.2 front and back cover. Illustration by Huriana Kopeke-Te Aho. Designed by Erin Broughton.

Correspondence is a biannual tabloid, publishing pairs of works for the page, web, and ear, as openings into artistic practices and relationships.

Correspondence 3.2 stems from the words 'resistance', 'action', and 'solidarity'. Contributors responded to these ideas in the context of the genocide taking place in Gaza and local and global reactions to this ongoing event. Java Bentley, Ayla Collin, Juanita Hepi and Keita Newbery each relate to Palestine through a connection to whenua and through whakapapa to Papatūānuku. Protest posters in the centrefold, created by Mengzhu Fu and Huriana Kopeke-Te Aho, are designed to be removed and pasted straight onto cardboard ready to take to a Pro-Palestine rally or placed in public view.

We hope you'll be able to pick up a copy from one of our listed distribution points below. No matter where you are in the motu, you can also enjoy this issue by downloading the full PDF, by listening using your screen reader, or by listening to the audiobook below.

Started by former Writing and Publications Coordinator, Hamish Petersen, Correspondence is a biannual tabloid produced by The Physics Room which explores forms of art writing in Aotearoa.

Contents

Ko Wai Mātou?

Editorial: Towards a Grammar of Animacy

Uho

Juanita Hepi

Kōwhekowheko, Ka Whakauka

Keita Newbery

Palestine Will Be Free

Mengzhu Fu

Aotearoa Ki Falastin: Toitū te Whenua, Toitū te Tangata

Huriana Kopeke-Te Aho

Gifting Back to Papatūānuku

Java Bentley

Rain and Redemption Begins With Papatūānuku: Tikanga as an Arawhiti and Extension of Self

Ayla Collin

Distribution

These are the sites who will be holding stacks of Correspondence 3.2 for free distribution to the public (limited supply):

Ōtautahi

The Physics Room

Ilam School of Fine Arts

Ōtepoti

Blue Oyster Art Gallery

Dunedin Polytechnic School of Art

Te Whanganui-a-Tara

Enjoy Contemporary Art Space

Massey University, Wellington CoCA Campus

Tāmaki Makaurau

Corban Estate Arts Centre

Fresh Gallery

Elam School of Fine Arts

Samoa House Library

And...

HOEA!,

Pātaka Art + Museum, Porirua

Australia

RMIT, Naarm

Melbourne Art Library, Naarm

VCA, Naarm

Details

Correspondence

3.2

July 2024

ISSN 2744-7529 (Print)

ISSN 2744-7537 (Online)

ISSN 2744-7545 (Sound recording)

Edited by Orissa Keane

Designed by Erin Broughton

Printed by Allied Press, Ōtepoti

Published by The Physics Room, Ōtautahi

Please note that the HTML text version of Correspondence 3.2 on this webpage is intended mainly for screen readers. If you're a sighted person, you might better enjoy the thoughtful design qualities of the downloadable PDF and print versions. The audiobook is there for all audiences to provide as an alternative way to engage with the contributions in this issue.

Ko Wai Mātou?

Java Bentley / My lived experience within a multicultural, urban and colonised framework has led me to where I am now. Choosing to embrace your whakapapa is a transformational journey that is an opportunity to rewrite, relearn and re-intent your power, your way. This is a privilege that my ancestors and kaumātua have fought for me and my reciprocity back to them is to continue to contribute as a kaitiaki.

I was born and raised in Tāmaki Makaurau. My māmā is from Ngāti Kahu and Ngāpuhi in Te Tai Tokerau. My tama was from Faatoia in Upolo, Samoa. My brother, sister and I are Māori, Samoan and Pākehā.

The tikanga that I bring with me to my mahi toi is my whānau at the centre. We wānanga and they are the reason I make. My kaiako and mentors from Toioho ki Āpiti, Te Pūtahi a Toi and Elam School of Fine Arts, University of Auckland have shaped and informed my journey and I am deeply thankful to them for the knowledge they have passed down to me. I acknowledge te taiao as interconnected and constantly changing as an opportunity for us to change and adapt as kaitiaki. As a sculptural installation artist, I focus on hangarua materials to present whakapapa and discuss the relationship tangata have with our everyday cultural landscape.

Ayla Collin / Ko Ayla tōku ingoa. I te taha o tōku māmā, ko Tinirau Akuira rāua ko Kato Akuira (Hawea / Ropata) ōku mātua tīpuna. He uri ahau nō Kahungunu, Rangitāne, Raukawa, me Toa Rangatira hoki. Nō Wairarapa ahau, he mokopuna o Wairarapa ahau. Ko Ngākau Waipunaahau tāku Māori Spice, tāku kōtiro nui, tāku ngākau. Understanding the multitudes of intersecting privileges I possess

and wanting to exist with reciprocity, the pātai remains for me, what is my contribution?

Mengzhu Fu / I am a 1.5 generation tauiwi of Han Chinese descent, born in northern China with ancestral connections to villages in central and southwest China. Tāmaki Makaurau is where I grew up with my parents and younger sister, near Maungakiekie, where a tōtara tree was cut down by Pākehā and replaced with a pine tree, symbolic of the colonial desire to replace Indigenous life with the settlers. Along with many others, I am involved in collective organising to build a future where all the land, power, language, and culture stolen from Māori, Palestinians, and Indigenous peoples everywhere can be restored and returned, and where the constitutional visions from Matike Mai Aotearoa are realised.

Juanita Hepi / Kāi Tahu, Waitaha, Kāti Māmoe, Ngātiwai, Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Kahungunu, Ngāti Mutunga, Moriori, Ngaiterangi. I walk around in a perpetual state of confusion telling yarns to find peace. I have some letters after my name, MMIL, GDip Tch and Ln, BA Acting, and no awards. I am a haututū, māmā and self proclaimed artivist who cannot sit still even though my Toi Whakaari research project was about silence and stillness, a metaphor ... For what? Well I haven’t quite figured that out but maybe it’s something to do with Kā Tiritiri o te Moana (the incredible Southern Alps), isolation, movement and sound as a trauma-coping mechanism, pūrākau, Whitestream arts and 300+ first cousins. When not lecturing, writing, curating, producing, directing, performing, advising, mentoring, adapting, dramaturging, or māmā-ing, I read reference and non fiction books, play Capitals of the World on Sporcle, get lost in the notion of there being no free will and rote learn the Māori and Latin names of New Zealand native plants. People say you will hear me before you see me (not sure that’s a good thing), and that I am a people connector and community builder. Aroha is free, capitalism is not, I’m only human, after all.

Orissa Keane / Tangata Tiriti and 1.5 generation tauiwi. My family is from Thailand, Switzerland and some further reaches of Europe on my mother’s side, and on my father’s they come from England, Ireland and Scotland. My older brother and I are Welsh-born, my parents moved us here when I was very young before having my younger brother. Ōtautahi is the home I know best; the house we have been in for more than 20 years now is sheltered by Ngā Kohatu Whakarakaraka o Tamatea Pōkai Whenua, the Port Hills, in view of Te Heru-o- Kahukura, Sugarloaf, which I could always see perfectly framed in my childhood bedroom window.

Huriana Kopeke-Te Aho / Ko Huriana Kopeke-Te Aho tōku ingoa, he uri ahau nō Tūhoe, Ngāti Porou, Rongowhakaata, Te Āti Haunui-a-Pāpārangi, Ngāti Kahungunu, Ngāi Tahu, Fale’ula (Hāmoa), Scotland, Ireland me Denmark. I am a self-taught artist and illustrator whose work is primarily influenced by

my Māori whakapapa, takatāpui identity, and political beliefs. At the centre of my artistic practice is a deep and fierce aroha/alofa for my people

and I aim to create imagery that speaks to the political and social struggles of my communities.

Mai te awa ki te moana. Ka whawhai tonu mātou. Āke, ake, ake!

Keita Newbery / Through my Tūhoe whakapapa I have always understood that we as an iwi are direct descendants from te taiao o Te Urewera. From

the union of Te Mauna and Hinepūkohurani came ‘nā tamariki o te kohu’. Our genesis lies directly with the land and Hinepūkohurani herself.

I grew up in the westside valley of Ōhinehou. I acknowledge nā mana whenua o Te Pātaka o Rākaihautū for the gratitude and love I have for the volcano crater I call home. Currently studying Heke Kaitiaki Pūtaiao at Te Whare Wānanga o Raukawa, I am dedicated to filling my kete with knowledge and tools to safeguard our natural world. Despite the ongoing injustices perpetrated by the Crown, our collective resilience ignites our fight to protect our taiao, gain equity for our people and assert our mana motuhake—āke ake ake!

Editorial: Towards a Grammar of Animacy

Orissa Keane

I recently learned that in the language of the Native American Potawatomi people, 70% of words are verbs, compared to English’s 30%.[1] In the book Braiding Sweetgrass, Robin Wall Kimmerer (Citizen Potawatomi Nation) writes about coming to terms with 'a Saturday', among other English nouns, being a verb—to be a Saturday. Kimmerer recalls the moment she could sense the bay as a verb, in being: "In that moment I could smell the water of the bay, watch it rock against the shore and hear it sift onto the sand. A bay is a noun only if water is dead. When bay is a noun, it is defined by humans, trapped between its shores and contained by the word. But the verb wiikwegamaa—to be a bay— releases the water from bondage and lets it live."[2]

Hearing this reminded me of Te Kawehau Hoskins and Alison Jones’ text (an extract from which was published in Correspondence 3.1) on the mana and mauri of Hongi Hika’s moko mark on the 1819 Kerikeri land deed: their discussion positioning this mark on paper as an action, something active and with energy.

What if we were to extend this ‘grammar of animacy’ (Kimmerer’s term) to include common words from our present context? In kōrero with Juanita Hepi about the kaupapa of this issue in its early stages, I chose the words ‘resistance’, ‘action’ and ‘solidarity’ as I explained my intentions. Juanita reminded me that resistance has a long history for Māori, and is a word directly attached to action, just as solidarity is. Specifically, I’m building on the idea of solidarity as a verb after Nadia Abu-Shanab and Matariki Williams. Both wrote for Pantograph Punch on standing in solidarity with Palestine in Aotearoa and the forms of action that this word, solidarity, implies. Nadia’s text reminds us of Aotearoa’s history of resistance and protest, and points to other organised protests by Indigenous peoples facing ongoing land alienation and expropriation.[3] Matariki, referring to Nadia’s text “Solidarity is a Verb”, adds that “artists are good at the doing”. She explains how “art has the ability to connect us to the horrifying in a way that acknowledges the humanity in us.”[4]

This is a small publication with a modest intention: it’s about exploring solidarity from the specific places where we stand. Among us are wāhine Māori and tangata Tiriti, seeking to connect to each other and to oppose what’s been happening in Palestine since October 2023 and for over 75 years before that. This means that this issue is about whenua and mana motuhake, land and Indigenous sovereignty, colonial violence and inheritance. Java Bentley, Ayla Collin, Mengzhu Fu, Juanita Hepi, Huriana Kopeke-Te Aho and Keita Newbery offer their own stories and those of others try to make sense of what we’re witnessing, to connect to Palestine through Papatūānuku, asking readers to do the same.

Last year’s Correspondence 3.1 explored artistic practice in the ever-changing context of a climate emergency, and issue 3.2 was going to extend more obviously from those themes. I had already engaged in kōrero with Java Bentley, whose work is embedded in whenua and tikanga. It was a lot to ask of Java

to pivot with me, as I did in redirecting this issue to focus on solidarity with Palestine and Toitū Te Tiriti.[5] After considering this new focus, Java sent me a mindmap. I noticed the way that words like hangarua, Papatūānuku, kaitiakitanga were connected with lines, like the diagram of a molecular structure, held stable by the whakataukī to the sides:

E tipu e rea mō ngā rā o tōu ao

Grow up, tender shoot, and fulfil the needs of your generation

And

He kura tangata, e kore e rokohanga, he kura whenua, ka rokohanga

Treasured possessions will not always be there, but treasured land will always be

Java’s “Gifting Back to Papatūānuku” draws from her mahi toi and recent masters exegesis. Just as the original mindmap she shared with me was a way to make sense of and connect the ground that she’s most familiar with to the whirlwind of global politics and escalating violence, I see the published map as an exercise in connecting with that which doesn’t make sense.

It’s increasingly difficult to think that local and global events can be separated out. Genocide and war is connected to climate change and ecocide is connected to capitalism and colonialism. The US military alone is a bigger polluter than entire countries.[6] War causes destruction of ecosystems and biodiversity as well as people. Within these pages Juanita Hepi states, “Gender-based violence continues as the leading form of violence in the world while land-based violence is the leading cause of climate change. Indige-femicide and ecocide are forever inextricably interlinked.”

Conflict is more profitable than peace. This is the title of the 2019 moving image work by Aliya Ali (Yemeni-Bosnian-US) which The Physics Room screened in March.[7] The line is repeated throughout the film; it stayed with me as I was trying to connect local and international acts of colonial aggression with ecological destruction, which is also a form of colonial violence.

Ayla Collin, in “Rain and Redemption Begins With Papatūānuku: Tikanga as an Arawhiti and Extension of Self”, describes a push and pull state. She identifies two distinct forces which contribute to her waning tolerance for living in what she calls the ‘other’ world. She can only stand to live in the Indigenous world. Ayla is rejecting the colonial, capitalist, predominantly white western worldview that encapsulates the governmental and corporate spaces she inhabits in favour of te ao Māori. “Rain and Redemption” is a record of the forces she’s been wrestling with, and a question, is it possible to choose?

Jumana Manna’s Foragers (2022) screened at The Physics Room in December 2024. Enjoy screened Inas Halabi’s We no longer prefer mountains (2023) during their exhibition The Centre Does Not Hold (2024). Both films point to the way Israel enforces its politics of land alienation and dispossession from behind a veil of environmental law and protection. Foragers depicts the resistance against the absurd protection laws which restrict Palestinians from foraging herbs and plants like za’atar and akkoub. We no longer prefer mountains, set in the Druze towns of Dalyet el Carmel, demonstrates how planting a tree can be an act of erasure. The film offers perspectives of the Druze people whose land is being co-opted and turned into National Parks. This status reduces their ownership to title only, and is another way that the Israeli government can control people and their land. Foragers and We no longer prefer mountains remind us of just how much irreversible damage can be done at a bureaucratic level.

In “Uho”, Juanita relates the violence enacted on Papatūānuku to acts of violence towards women, through colonisation and its ongoing effects. Uho is a word for the heart centre of a tree or an umbilical cord, and is one in a list of kupu which have distinct meanings to do with both whenua and wāhine. Tangata whenua have witnessed the colonial transformation of their land, and the Crown’s disregard for iwi and whenua is as present as ever in the policies of the current coalition government.

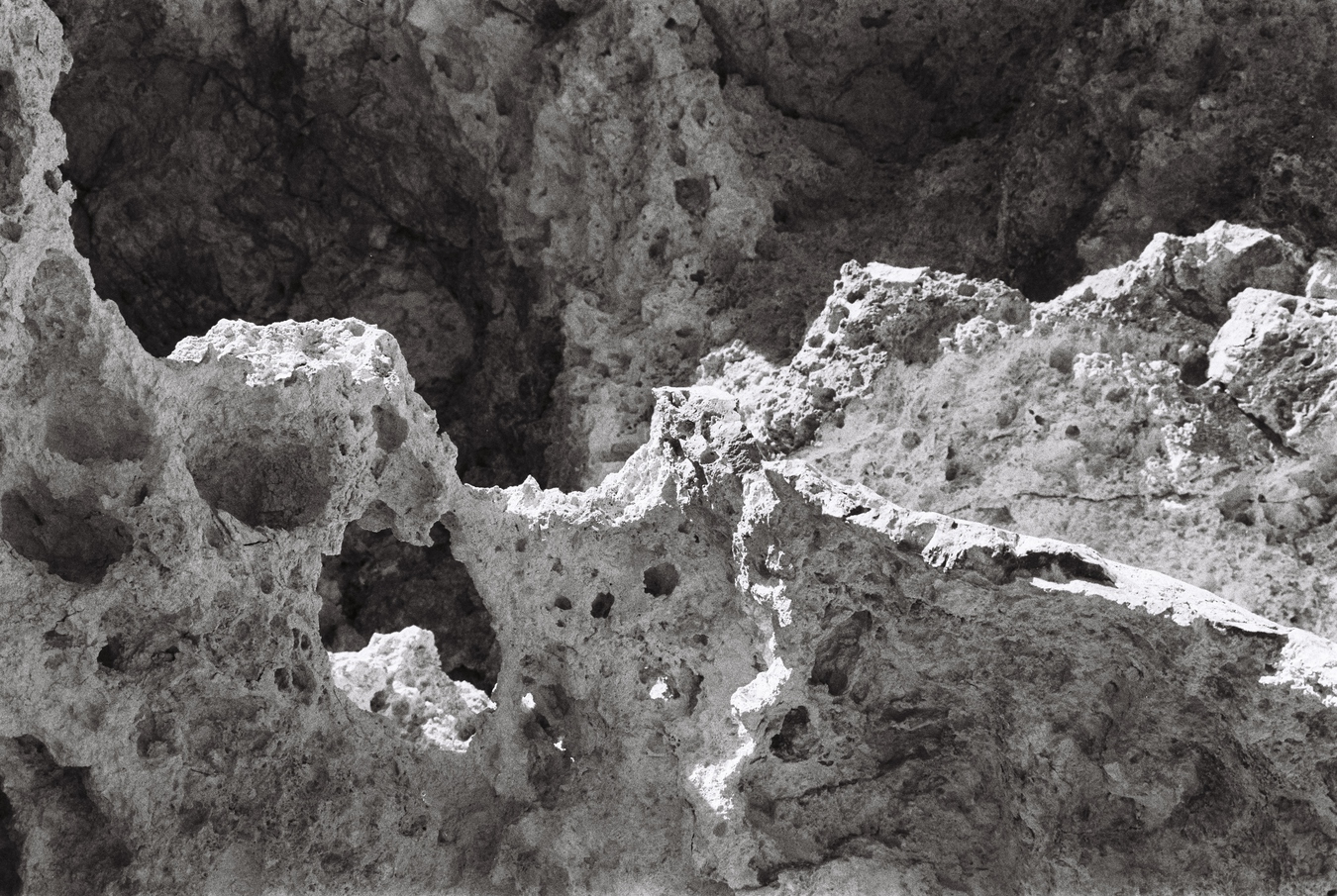

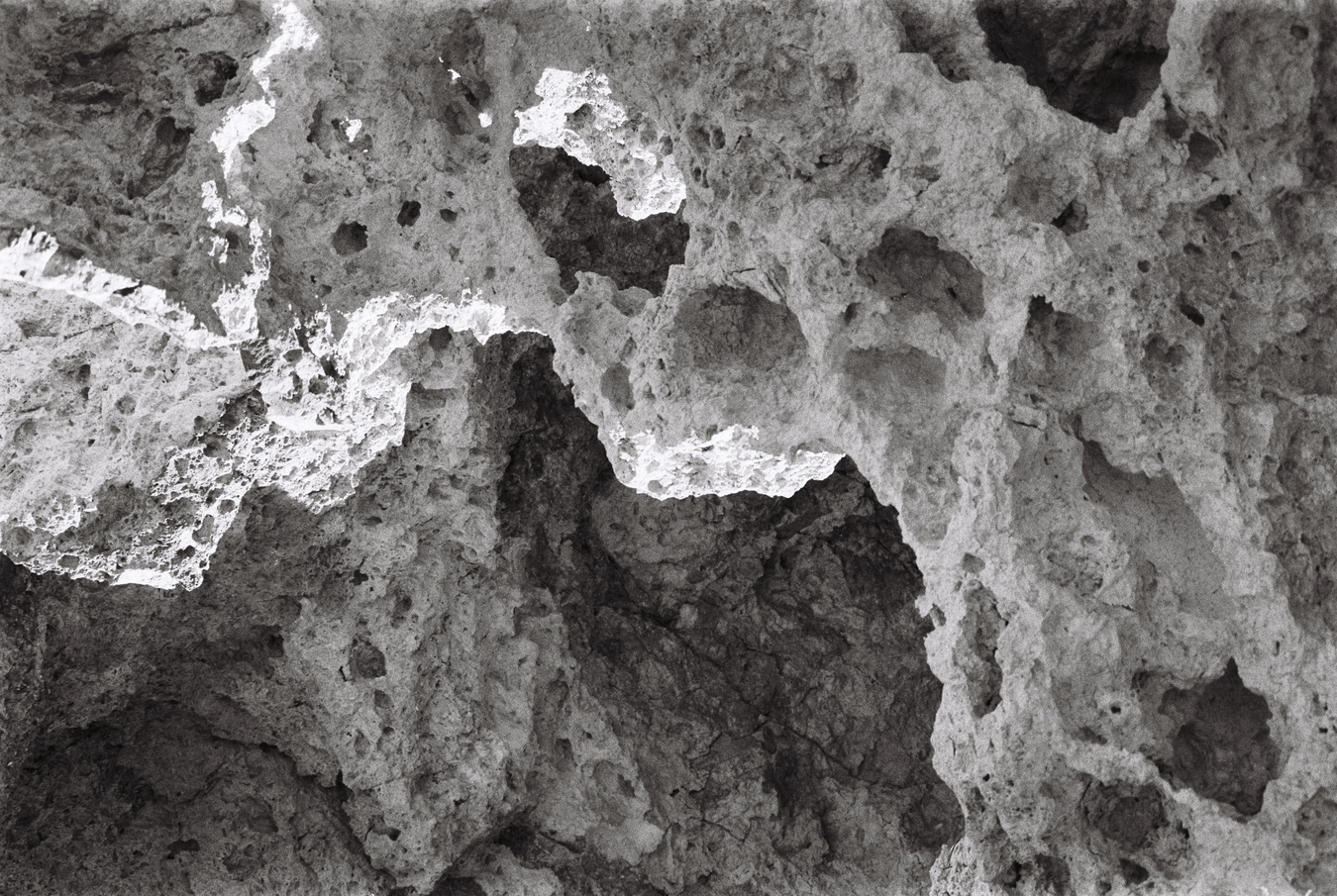

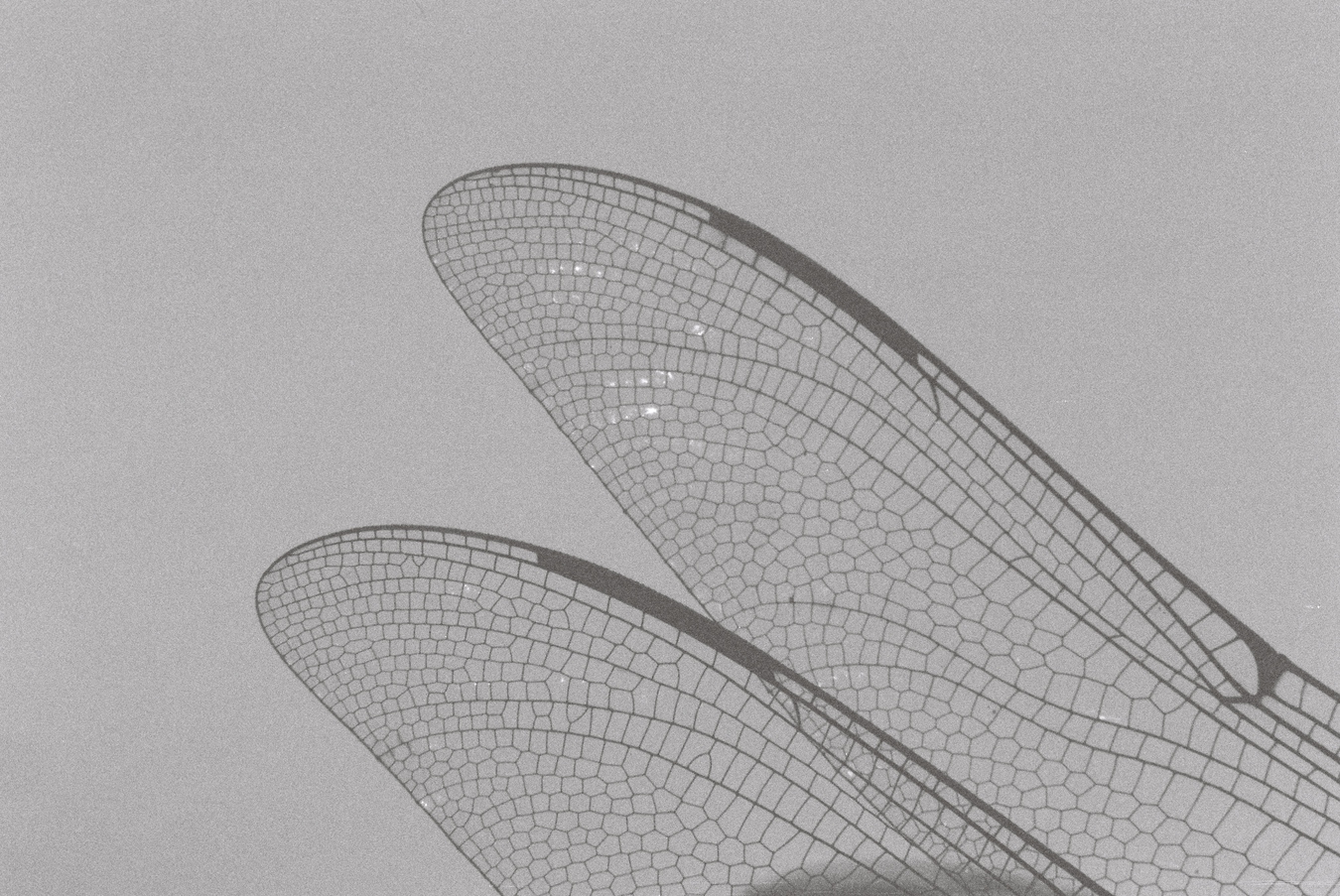

Keita Newbery’s Kōwhekowheko, Ka Whakauka is a series of black and white photographs taken on 35mm film. Responding to Juanita’s text, Keita made journeys to Te Pātaka o Rākaihautū (Banks Peninsula), Hokitika, and Arthur’s Pass in Kā Tiritiri o te Moana (the Southern Alps) to capture these photographs. Keita told me that the images all relate to Te Waipounamu and the plants and creatures that have existed along with the whenua since prehistoric times, able to bear witness to the arrival of tangata Māori (te ao Māori pre-colonisation) and the subsequent changes to geography, ecosystems and people due to the catastrophes of colonisation.

Returning to the idea of solidarity as a verb, I would like to make some suggestions: be vocal, and show up. Your voice counts, whether it’s heard within your whānau, friend group or at your workplace. Your presence at rallies and gatherings counts. Mengzhu Fu and Huriana Kopeke-Te Aho have created posters which you’ll find in the centrefold. The beautiful and eerie sky in Mengzhu’s was inspired by Palestinian journalists who would live-stream sunsets from Gaza. The white kite has come to evoke the memory of the beloved poet Refaat Alareer who wrote “If I Must Die” before he was assassinated by the IOF in Gaza.[8] Huriana’s cover illustration takes the silhouettes of an olive tree, native to Palestine, and a kahikatea, a tree indigenous to Aotearoa said to connect Te Ao Mārama and Te Ao Wairua.

Consider how the act of reading itself can contribute to resistance and solidarity, and activate Correspondence 3.2 by discussing it with friends and family. Take the posters, stick them on cardboard and take them to your local rally, or paste them up somewhere they’ll be noticed.

Photo: Sign on the door to The Physics Room on Saturday, May 11 2024.

1. Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass (Minneapolis, Minnesota: Milkweed Editions, 2013), 48-66.

2. Ibid.

3. Nadia Abu-Shanab, “Solidarity is a Verb”, Pantograph Punch, 2023. Accessed May 2024. https://www.pantograph-punch.com/ posts/solidarity-is-a-verb

4. Matariki Williams, “Art is a Salve”, Pantograph Punch, 2024. Accessed May 2024. https:// www.pantograph-punch.com/posts/art-is- a-salve

5. The Toitū Te Tiriti movement was initiated by Te Pāti Māori at the end of 2023. Toitū is a word for permanence and wholeness; toitū Te Tiriti means honour the treaty, Te Tiriti o Waitangi. The movement, or ‘activations’ as the party calls them, is to unify Māori and tangata Tiriti (people of Te Tiriti) against the current government’s actions to undermine the principles of the Treaty and Māori.

6. “The US military is vast in scale, with a carbon footprint larger than any other institution on earth.” Lorraine Mallinder, “‘Elephant in the room’: The US military’s devastating carbon footprint”, Al Jazeera, 12 December 2023. Accessed May 2024. https://www.aljazeera. com/news/2023/12/12/elephant-in-the- room-the-us-militarys-devastating-carbon- footprint

7. In November 2023 The Physics Room along with numerous other galleries, made a commitment to educating and raising awareness of Israeli genocide against Palestinians in Gaza. This has manifested as screenings of films and moving image artworks by Palestinian and Indigenous artists, among other events such as lectures and protest sign-making workshops.

8. Israel Occupation Forces or Israel Offensive Forces are pejorative terms for the Israel Defense Forces in Palestine.

Note: Te Aka Māori Dictionary online is a useful general reference for te reo Māori words.

Uho

Juanita Hepi

HINEATAUIRA (Kāi Tahu specific):

In the mediocre writing of my masters thesis are the expertly written words of prominent Māori and Indigenous thinkers, the majority of whom are wāhine Māori. I’ve resurrected parts of the original unpublished thesis to expand on the extractive ways wāhine Māori are forced into violent encounters, especially in the arts via visual representation, and especially where land is concerned. I celebrate those same wāhine, the ones who have consistently resisted colonial narratives, by honoring their names and their words once more. Although I write passionately from a wāhine Māori perspective, writing about mana wāhine or wāhine Māori or any other mātauraka concept in English only half uncovers truths.

Of the wāhine in this essay, some of them I know, some I’ll never meet and others are unknown outside of their whānau, hapū and iwi. These wāhine are not the exception, they are the rule.

"They are women of substance, women of exalted lineage,"

they "have their own power,"

they "are wāhine rangatira in their own right, formidable inspiring women who were at the forefront of battles, decision making and commercial opportunities."

"You find powerful women everywhere."[1]

We are connected through a web of relations, blood and social ties we call whakapapa. In te reo Māori there are thousands of words for how to be in relation with. Our whakapapa extends into the peoplehood of plants and animals in one mechanical rhythm we call wā, time/space/past/present/ future. This was, of course, before the arrival of the Trinity—the thief, the cross and the peoples—before Tasman and Cook armed with discovery doctrines, before stereotypes, before God, before Shakespeare and the written word, before the White man and his property, White women, before patriarchy, before the settler state, before I was different and lesser than.

"‘It appears that people prefer the dreamy, half-naked, idealised version of wāhine Māori to the powerful and complex reality.’ When considering why this might be, one woman responded, ‘That’s because one hangs in their living room and the other hangs in their conscience.’"[2]

Don’t worry, I’m not going to centre the Dusky Maiden or the deficit-theorised Angry Brown Woman like an over-produced false-reality-series. They’re convenient tropes spiralling from the unbearable air of White supremacy—yes, that uncreative design. Plus, this isn’t a disquisition on ‘me’, the ‘I’ or the ‘ego’, although from a Māori perspective the ‘i’ is the ‘We’.[3] I need to sit down, shut up, and let the wāhine do the talking. These wāhine words and worlds that I’ve embodied have become a part of my vocabulary and whakaaro, almost like one intergenerational voice saying ‘me aro koe ki te hā o Hineahuone’.

HINE AHU ONE:

Hine Ahu One is the first human woman, made from mud and clay, possibly loved, maybe violated; it’s unclear the extent to which “colonial catharsis” has distorted wāhine Māori stories.[4] But herstory is powerful enough to have withstood an environment in which Māori storytellers were silenced and their severed stories lay in museums, galleries, university publications and laboratories around the world (almost always without permission or Indigenous possession). Hine Ahu One and her many stories remain as a gatekeeper to the worlds between us. In herstory, she is born as Hine Ahu One. When Tāne (the first human man) becomes her husband, she becomes Hine Titama. One day she asks the ancestors about her parents and learns the incestuous truth; that her father is her husband, a lie he has upheld and admits to. Hine Titama flees to Te Pō where she renames herself Hine Nui Te Pō. From here, Hine Nui Te Pō makes the ultimate sacrifice, leaving her children in the land of the living while she moves to the spiritual world where she waits for her puna, her offspring, me, to guide us to our final jumping off place at Te Rerenga Wairua, when my body dies.

"In so doing, Hine-nui-te-pō should have risen triumphant, don’t you think? Instead, she was demonised. Like her sister Mahuika, and daughter Muri-ranga- whenua, she was introduced in menacing imagery ... But the most despicable focus was on the representation of her outer genitalia as having a monstrous life of their own."[5]

Dr Ranginui Walker implicates Anglican missionaries who were intent on converting Māori from ‘barbarism to civilisation’ as early as 1814 which included re-writing Māori stories to fit with religious ideologies.[6] In Hyland’s words, “our stories lost their female protagonists, and our archetypes were sullied by Western cyphers”.[7] Eurocentric narratives about the ‘noble savage’ and the ‘dusky maiden’ replaced Māori narratives about themselves and Māori women were re-framed as ‘degraded’ and ‘savage heathens’.[8]

Our stories that once celebrated the blood that ran from our wombs now misrepresented wāhine bodies as dismembered and inferior objects. Very quickly wāhine Māori lived realities were experienced in the same way, more inhuman than human. Now we are forced to quantify and qualify our own human-ness (or people-ness) which disconnects us from each other and from our mother, Papatūānuku.

PAPATŪĀNUKU:

All wāhine Māori whakapapa back to Papatūānuku (whenua/the land). Our very belief system is entrenched in the soil beneath our feet, so that what happens to whenua is what happens to us. And beyond Aotearoa: berated, owned, raped, diamonds extracted from organs and sinew, tearing flesh from bone to get to the good parts, the parts that build devices to ‘help’ things like communication and capitalism—like this Mac I’m writing on. Our waters run red and black and brown, unnaturally if they run at all, and in the invisible heart beat of Papatūānuku, I can feel her dying, but before she goes, I will go first, and by ‘I’, i mean ‘We’.

"The whenua knows our pain. Generations of loss, hurt and violence stain the soil. Broken promises and lost dreams lie scattered across the land like discarded weapons on a battlefield."[9]

Despite traces of the land being visible in the creases on the faces of every Māori child born today, the historical amnesia by inhabitants of so-called New Zealand who can barely muster a whisper about the desecration and rape of both Māori land and Māori women speak a deafening silence. Gender-based violence continues as the leading form of violence in the world, while land-based violence is the leading cause of climate change. Indige-femicide and ecocide are forever inextricably interlinked. How much has changed? Turn to any clickbait, commercial or marketing campaign and you will see the objectified, disconnected body parts of mostly young women fetishised, infantilised and sold, between the headlines that sprout environmental destruction, devastation and species extinction. Cameron Russell reminds us that these are “constructions by a group of professionals”, and that underlying the (re)constructed sexualised child and disembodied teenager is an invisible discussion about race, class and politics as it pertains to the non-White body.[10]

Again it is left to us, women/wāhine, the victims, to utter those heinous words belonging to those swept-under-the-colonial-carpet crimes. Our focus should be on the stories of the women and land, however the silent instigators at the margins are the mostly male perpetrators who continue to get away with crimes of violence against Indigenous women, children and land. Violence, however, is not the only story of our lives. Linda Tuhiwai Smith reminds us,

"we cannot assume that the lives of all Māori women have been shaped by the same kinds of forces [...] it is critical that we do not fall into the colonial, reductionist trap of assuming that there is one, singular truth or version in regards to how we understand our ways of being."[11]

Therefore the assertion of our mana motuhake as a people and the articulation of mana wahine is essential in countering the impact of over 170 years of oppressive colonial practices.[12]

The articulation of mana wāhine is inseparable from the articulation of mana whenua, so it’s no surprise that in te reo Māori, words to do with whenua are words to do with wāhine.

Whenua = Land + placenta

Hapū= Kinship group, subtribe + pregnancy

Uho = Heart of a tree + umbilical cord

Rauru = Three plait weaving + umbilical cord (part nearest the mother)

Ihu = Pith of a tree + umbilical cord (middle part)

Kākano = Seed, kernel, pip, berry, grain + ova, ovum, egg cell

Kōmata = Young, tender shoots of plants + nipple (of the breast)

It is here in the words of our language that wāhine Māori can find their truth, far from the hegemony of the settler state, but close to the uho, rauru and iho. So interconnected are wāhine and whenua that one without the other signals death as is reinforced in the following well-known whakataukī.

'He wāhine, he whenua mate ai te tangata.'

'By women or land, [hu]man is defeated.'

In an uncertain time of livestreamed genocide, economic disaster, climate change, mis- and dis-information, a focus on wāhine Māori may feel irrelevant, however these crises are interlinked because they are borne from the same colonising seeds. For Māori women, it has been a sneaky constant since the arrival of Captain Cook to Aotearoa when he murdered their sons and let syphilitic abusers loose on their lands and children. You don’t have to look far to find the manuscripts and literary evidence of coloniser and settler violence against wāhine Māori or its modern day media equivalents ... but you do have to look.

HINE NUI TE PŌ:

In her detailed essay, “Māori Women; Caught in the Contradictions of a Colonised Reality,” Ani Mikaere explains how colonial policies have had the most profound impact on wāhine Māori and their whānau.[13] Wāhine Māori have been deliberately severed from their traditional leadership roles, ancestral lands, language, and culture using oppressive and assimilationist measures funded by the state and designed to further exploit Indigenous resources, perpetuating the Crown’s cycle of dispossession and violence.

The WAI 2700 Report, commonly known as the Mana Wāhine Inquiry, is a staggering document of over thirty years of info-gathering, legislative frameworks, pūrākau as methodology, tikaka and hundreds of years of wāhine Māori voices connecting across the wā. It is a gift from those who have come before me, a reminder that in no world am I a second class citizen and in no world am I a slave to the disturbing operation of settler colonialism. Specifically I refer to the Brief of Evidence of Katarina Jean Te Huia who describes the incommensurable nature of Indigenous and Western philosophies. Te Huia cites Usogo, who "argues that one of the most noticeable differences between the Western Society and its non-western counterparts is the individual’s perception. Individualism flourishes, and is often associated with capitalism, materialism, alienation, and self-centredness, and is perpetuated by the formation of a privileged class, the impetus that increasingly brings joy from the wealth, power and status separating it from the non-western population, at the expense of them, their culture, their resources and eventually their lives."[14]

At this point I explicitly recognise my own entitlement, the entitlement

of being educated and how that allows me to write today, the entitlement

of film, TV and international work that has led to my ‘being seen’ by the Whitestream consequently bolstering my opportunities, power, money, status. The entitlement of being a ‘marae girl’ having grown up just over the hill within the warm (albeit hurt) whānau spaces of both my Māori māmā and Māori pāpā. It is precisely these spaces that produce artivists like me.

In her WAI 2700 prologue, Katerina Jean Te Huia establishes the basis of what this essay is really about, and in doing so joins a long line of wāhine who consistently open the way for the Crown and this country to repair and reaffirm the mana of wāhine Māori, their pēpi, tamariki and whānau.

In my response to this Mana Wāhine inquiry I acknowledge wāhine Māori voices, and wāhine Māori perspectives which are deliberately and purposefully prioritised. Māori, and especially wāhine Māori as the Indigenous people of Aotearoa share similar negative life experiences as other Indigenous peoples across the world, beginning with the assaults on wāhine Māori as women and mothers. We are not alone in our attempts to gain recognition of our human rights. As other Indigenous peoples across the world have exposed their battles against British colonisation, so too do we as wāhine Māori in Aotearoa bear witness to the same atrocities’, the same rapes, the deliberate ongoing assimilation policies that deny us our world of Te Ao Māori. We are exposed to the same calculated outcomes of destruction targeted at our pēpi, at us as indigenous mothers and indigenous fathers, in our homes, our language, our values, and beliefs and ultimately and purposely aimed at our resources.

In seeking new ways to accentuate my experience, in this case, through the written word, my goal has been to rewrite our women past the history books and back into our oratory where they may forever shine as kā whetu āriki o Hineraukatauri. Our stories are of resistance, revitalisation, rejuvenation and reimagination. As Honor Ford Smith writes,

"The tale-telling tradition contains what is most poetically true about our struggles. The tales are one place where the most subversive elements of our history can be safely lodged ..."[15]

Storytelling then, is a powerful medium for social change when in relation with Indigenous communities.

"The old woman sang of a time gone ahead, and of those already walking ahead of her on the pathway. Her eyes were reddened as though they bled. And her songs, like the pathways, were interweavings of times and places and of all that breathed between earth and sky."[16]

1. Quotes from Pomare, Salmond, Smith, Te Awekotuku and Tobin are italicised. M. Pomare, A. Salmond, L.T. Smith, N. Te Awekotuku, E. Tobin, “Mana Wahine,” June 6, 2017, YouTube video, https://www. youtube.com/watch?v=WhtuXXEQOV0&t=1s.

2. Here, I am quoting the author recounting a group discussion: “I discussed the project with a group of Māori women based on the images available on Pearce’s social media, which offer sexualised images of wāhine Māori.” Nicole Titihuia Hawkins, “You can’t copyright culture, but damn I wish you could,” The Spinoff, (2018): accessed 2024, https://thespinoff.co.nz/atea/20-03-2018/you-cant-copyright-culture- but-damn-i-wish-you-could.

3. Decapitalising the ‘i’ and capitalising ‘We’ in this sentence is a purposeful act of decolonising language, where the individual is decentered in favour of recentering groups of communities. I’ve kept the English text as grammatically correct as possible, and took this moment as a learning opportunity.

4. Nicola Hyland, “A Conscious Un-couplet: Wahine Maori Stand Up to Shakespeare,” Australasian Drama Studies 73, (2018): 207-236.

5. In te ao Māori, names, stories and places may have slight variations depending on the storyteller. For example, Hinenuitepō can be written as Hine-Nui-Te-Pō and Hine Nui te Pō. Often these variations occur for dialectal or geographical differences. Witi Ihimaera, “The redemption of Hine-nui-te-pō,” The Spinoff, October 21, 2020, accessed 2024, https://thespinoff.co.nz/books/21-10-2020/the- redemption-of-hine-nui-te-po.

6. Ranginui Walker writes: “Although the culture of New Zealand’s tangata whenua, with its hunting, fish- ing, gathering and gardening economy, was a sustainable design for living, it was almost destroyed by the colonial enterprise of converting the natives from barbarism to Christianity and civilisation. British colonisers saw Māori tribalism and communal ownership of land as the mark of primitive and barbaric people.” Ranginui Walker, “Reclaiming Māori education,” Decolonisation in Aotearoa: Education, research and practice, 2016, 19-38. (Wellington: NZCER, 2016), 19–38. And Marianne Schultz, “A ‘Harmony of Frenzy’: Māori in Manhattan,” Theatre Journal 67(3), 2015, 1909–10, 445-464. doi:10.1353/tj.2015.0074

7. Hyland, “A Conscious Un-couplet,” 207-236.

8. Tanya Fitzgerald, “Archives of memory and memories of archive: CMS women’s letters and diaries 1823– 35,” History of Education 34(6), 2005, 657–674, accessed 2024, https://doi-org.ezproxy.canterbury.ac. nz/10.1080/00467600500313948.

9. Aroha Gilling, “Whispers from the whenua”, E-Tangata, 2024, accessed 2024. https://e-tangata.co.nz/ reflections/whispers-from-the-whenua/

10. Cameron Russell, “Looks aren’t everything. Believe me I’m a model,” 2012, TED Conferences video, https://www.ted.com/talks/cameron_russell_looks_aren_t_everything_believe_me_i_m_a_ model?trigger=0s

11. Linda Tuhiwai Smith, “Māori Women: Discourses, Projects and Mana Wahine,” Mana wahine reader: Vol. 1. A collection of writings 1987- 1998, eds. Leonie Pihama, Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Naomi Simmonds, Joeliee Seed-Pihama and Kirsten Gabel (Hamilton: Te Kotahi Research Institute, 2019), 41.

12. Leonie Pihama, “Mana atua, mana tangata, mana wahine,” Mana wahine reader: Vol. 2. A collection of writings 1999-2019, eds. Leonie Pihama, Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Naomi Simmonds, Joeliee Seed- Pihama and Kirsten Gabel (Hamilton: Te Kotahi Research Institute, 2019), 193.

13. This article explores the role of women in Māori society prior to colonisation. It subsequently delves into the status of women under English law, scrutinising the ramifications this legal system imposed on Māori women in the wake of colonisation. Highly recommended reading.

14. Katarina Jean Te Huia, WAI 2700, July 27, 2022, 6, citing Kenneth Usongo, “The Cultural and Historical Heritage of Colonialism,” Interrogating the Postcolony (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2022), 3.

15. Aman Sium, Eric Ritskes, “Speaking truth to power: Indigenous storytelling as an act of living resistance,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 2(1), 2013, 1-10.

16. Patricia Grace, Potiki (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1995), 180.

Kōwhekowheko, Ka Whakauka

Keita Newbery

Keita Newbery, Kōwhekowheko, Ka Whakauka, 2024. 35mm black and white film photographs.

Rauru

Rauru 2

Huritao

Waihona

Uruururoroa

Mā Raro

Angiangi

Palestine Will Be Free

Mengzhu Fu

Aotearoa Ki Falastin: Toitū te Whenua, Toitū te Tangata

Huriana Kopeke-Te Aho

Gifting Back to Papatūānuku

Java Bentley

I visited Te Rā at Tāmaki Paenga Hira Auckland War Memorial Museum. She is known as the only surviving customary Māori sail and her journey of life shares with us mātauranga and whakapapa of Pasifika navigation.

^

While she returns back to the British Museum her siblings, Hine Mārama and Mahere Tū ki Te Rangi woven by the rōpū Te Rā Ringa Raupā stay in Aotearoa as holders of her mana and collective history. As replicas of Te Rā, they house another life and new mauri that remembers the provenance that Te Rā keeps safely to herself.

^

Just as Te Rā informed Hine Mārama and Mahere Tū ki te Rangi, Papatūānuku shares her stories and memories with us through all living things. Resources and materials that we consume every day speak to the life of Papatūānuku and through the context of kaitiakitanga we are the conduit between the wellness of the whenua and Papatūānuku.

^

Sustainability refers to sustaining or maintaining the balance of a process over time. Kaitiakitanga as a concept of guardianship speaks to the sky, sea and the land. Reciprocity is important in sustaining and protecting Papatūānuku so that she can continue to sustain and protect our next generation.

^

How we can practise, how we can be informed and inspired by Papatūānuku, is by finding ways to share what we know, so we can be resilient and self-sufficient.

^

My karanga to Papatūānuku is through mahi toi. Going back to the beginning, my kaupapa traces the origin of whakapapa— Papatūānuku—in order to celebrate all things as sacred.

^

Papatūānuku represents collective making and the creation of all things.

^

Together as wāhine through our own shared experiences, giving and receiving of memory is the building of whakapapa. This text explores collaboration between Orissa, Ayla and I coming together through our shared experiences to create meaningful rangahau.

Te Whenua ~ reciprocity between us and Papatūānuku, giving back to the land. The land giving to tangata, tangata whenua.

^

This writing comes from a very intense space of gratitude to my kaiako, the privilege of learning and unearthing myself through completing my masters. Continuing resilience in self empowerment, self sufficiency and self healing is through connection.

^

Why am I here and in what ways can I contribute to you, Papatūānuku?

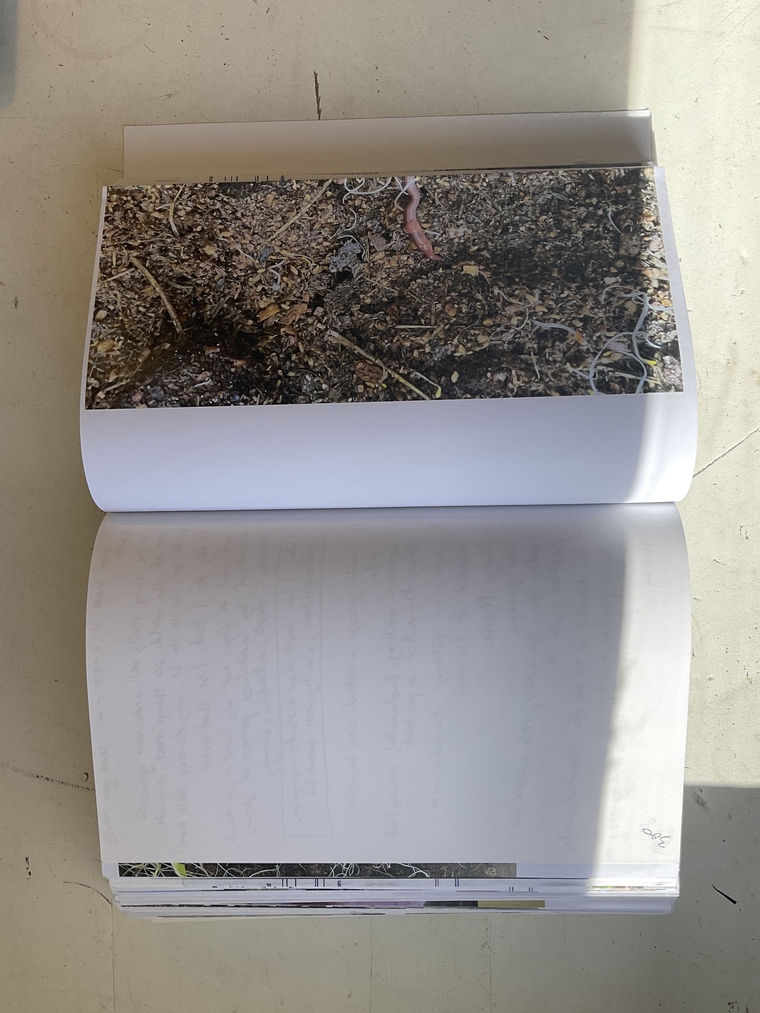

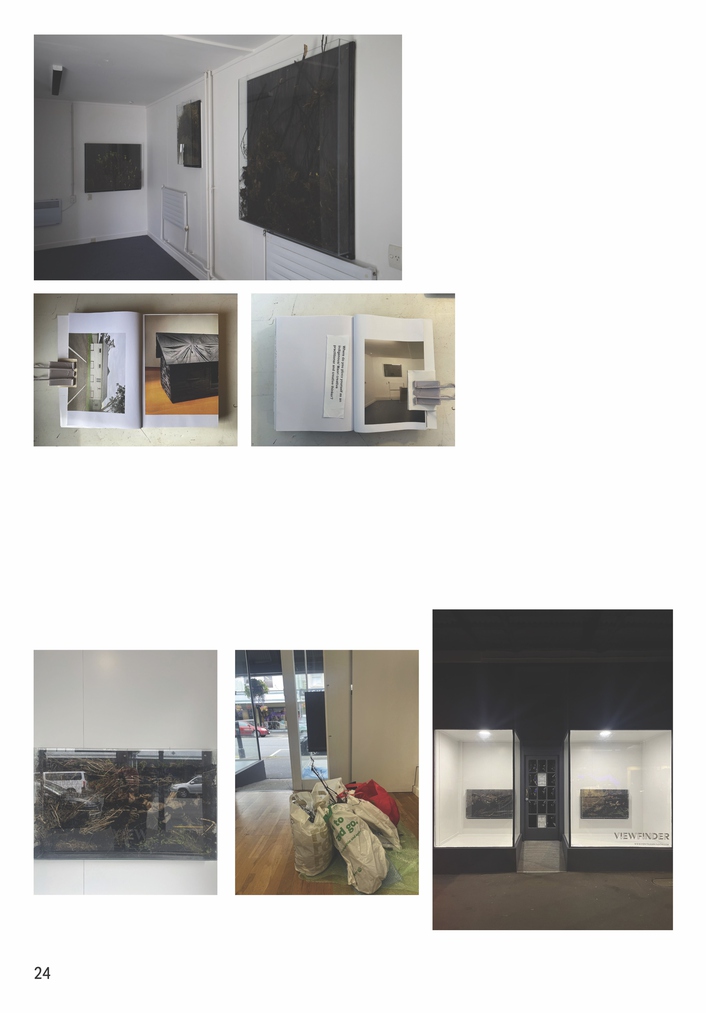

As an artist informed by the environment, my journey questions how my impact invites intention. I was graciously asked to re-present mahi toi developed in my Masters of Māori Visual Arts in a new context and space. As part of the journey from Tāmaki Makaurau to Whakatū, my māmā and I brought compost from our home as a gift to Viewfinder Window gallery in Whakatū. But the journey was also a reciprocal one from Whakatū to Tāmaki Makaurau.

^

This work, Mata-onerua, was a new iteration of my final exhibition for my Masters of Māori Visual Arts at Toioho ki Āpiti. The title speaks to the eyes or windows intocompost. The intention of the work was to koha materials from my home in Tāmaki Makaurau to Whakatū in the form of compost. Not yet fully transformed, the process of composting is the work. Bridging across the motu and the gifting of compost from my kāinga, as in my home māra, to Whakatū was an intentional act of gratitude, connection—not confiscation.

^

I attended a public programme kōrero with artist, actor and architect Raukura Turei and artist and curator Nathan Pōhio for the exhibition underfoot (2024) at Te Uru Waitākere Contemporary Gallery in Tāmaki Makaurau. In conversation with curator James Gatt, they discussed te whenua in relation to their practices, positionalities and whakapapa. Turei spoke about the process of gathering materials as intentionally informed by rohe, iwi and connection. What I took from her kōrero in relation to my mahi toi was to be intentional with te whenua in karakia and tikanga. I acknowledge my iwi as Ngāti Kahu and Ngāpuhi and my Sāmoan and Pākehā heritage. Living in my family home in Tāmaki Makaurau, I gifted plant clippings, dried leaves and dropped branches from our māra that has enriched my whānau.

^

Mata-onerua, 2024, koha onerua from Tāmaki Makaurau to Whakatū encased within onerua containers, Viewfinder Window Gallery, Whakatū. Ngā mihi to Katie Pascoe, Lee Woodman, Kim Ireland, Sarah McSharp and Inez Crawford.

^

Onerua ~ second life of soil, compost

^

Onerua was a kupu gifted to me by Toioho ki Āpiti senior tutor, Te Ataarangi kaiako and artist Karangawai Marsh, connecting oneone and hangarua. In this way, onerua takes on the meaning of the second life cycle of soil.

^

The decision to connect with you, Papatūānuku, was to find out how I could make meaningful connections that make sense to me and how I could apply these foundations for the benefit of my nieces. Knowledge is collective, expanding—acknowledging the multiple paths that tangata can take—building foundations so that our younger people can choose their own.

^

Between 2022 and 2024, I studied my Masters of Māori Visual Arts at Toioho ki Āpiti in Te Papaioea. This journey for me was about understanding my role as a kaitiaki of the natural world, and focusing on the environment around me. The mauri or life force of materials is a way to make relationships with all things living, whakapapa. By tracing the whakapapa of all materials to the whenua, you discover the interconnectedness of everything. This kaupapa I nurtured at University was an opportunity to give new life to Papatūānuku.

^

Hei whare onerua reflects onerua site-specific to Te Papaioea. Looking at onerua through the lens of Te Pō, the potential of the night, I created a total of eight onerua containers that replace the interior windows in the Cubeside Annex at Te Pūtahi a Toi. Over the course of the exhibition, the transformation of materials enabled growth. Artist, academic and educator Kura Te Waru Rewiri gifted compost to Hei whare onerua. Her gift of compost as support and as my mentor strengthened the mauri of the onerua and I honour her always.

^

I attended the kōrero with Ngāti Kahu leader, author and academic Margaret Mutu and singer, songwriter and documentary maker Moana Maniapoto on behalf of the Auckland Women’s Centre at Samoa House, where they discussed Te Tiriti o Waitangi within our current political and environmental climate. Mutu spoke about the reality of our tūpuna inviting manuhiri to Aotearoa and the responsibilities Māori have to Papatūānuku to look after one another. Manaakitanga as a fundamental value of Aotearoa being a Māori country and the knowledge that Māori have as mana whenua, Mutu reaffirms this responsibility of the roles of Māori and tauiwi to Papatūānuku.

^

Hei whare onerua, 2023, onerua and oneone encased in onerua containers, Cubeside Annex at Te Pūtahi a Toi, Massey University, Te Papaioea. Ngā mihi to Karangawai Marsh, Kura Te Waru Rewiri and Prof Huhana Smith.

^

New mauri ~ the transformational potential of something new

^

Mauri is the lifeforce, potential, energy or essence of all things. New mauri is continuing the cycle of life forces, potentials, energies or essences of all things. This cycle is the foundation that builds whakapapa.

^

Materials have many lives. Mauri, like energy and potential, is moving and constantly renewing. New mauri as a concept was developed in my masters and was guided by Karangawai who has deeply informed my kaupapa and who I am forever grateful to.

^

The method of making this writing has been a collaborative and binding experience that has been a complex exchange of rangahau, wānanga and koha working together online from different cities. Ayla and Ngākau posted to me a package of gifts to respond to and build from to create this mind map of whakapapa.

^

Receiving taonga or gifts is a contribution to a continuing relationship and building of whakapapa. Informed by the tikanga and rituals involved in the giving and receiving of koha in return, my gift back to Ayla and Ngākau is this work.

^

The kōrero Ayla gave me around her watercolour on paper was a collaborative exchange as māmā and pēpi, symbolically using watermelon to speak to seeds as a bridge that extends to growth but also a gesture to all mothers and children. Intentionally ripped into segments, I felt this as a sharing of kai and expression of manaakitanga. As a response to Ayla’s work and the platform of this writing piece, I wanted to acknowledge the cyclical relationship of seeds. Planting Ayla’s watermelon into the whenua located at my home speaks to the planting of knowledge and binding of whakapapa.

^

Te kaimānga a ngā tūpuna

The masticated food of the ancestors

^

This whakataukī is a connection to mothers chewing food or knowledge to feed and sustain us. Onerua is both the nourishment of the whenua and for us is also the deposit of knowledge that Papatūānuku has given us. Breaking up our daily routines and making intentional decisions with what we do with waste is how we can understand the impact we have in our own environments. Reusing our resources is giving back to Papatūānuku.

^

Ayla, Ngākau and Java, 2024, composted watercolour on paper, Wairarapa and

Tāmaki Makaurau.

^

Hangarua ~ enables a new cycle of life, reuse potential and creates new mauri for materials

^

I attended day three of He Whenua Rongo: Indigenous Seed, Soil and Food Sovereignty at Papatūānuku Kōkiri Marae in Onehunga, Tāmaki Makaurau. The kaupapa, deeply rooted in the healing of Papatūānuku, was evident in the kōrero and whakaaro—most importantly evident in the community, experience and cultural landscape of Aotearoa.

^

The recurring phrase throughout the symposium that stayed with me was the right to self-sufficiency through the reconnection to whenua and kai. Looking to Papatūānuku, Kōkiri Marae is guided by Kaiwhakahaere Valerie and Lionel Hotene: they share their wealth of māra kai, knowledge of composting and healing of the whenua with their whānau, community and iwi.

^

Composting your own kai is an empowering method of creating whenua that you know and understand. Compost is te whenua. The kupu onerua further connects the importance of tangata as a conduit for Papatūānuku.

^

The methodology of hangarua is an extension of gratitude to Papatūānuku. To reuse materials through the lens of whenua is to see all materials as sacred and whakapapa.

^

Ayla mentioned in our kōrero the importance of arawhiti, bridges, which Orissa has exemplified by making connections and fuelling whakaaro. Orissa reminded me of a work I created in 2019 that continues to be unearthed and a reconnection with others, Auckland Flowers 15/03/2019 presented at Corban Estate Arts Centre, Tāmaki Makaurau. Through wānanga, I acknowledge Orissa and Ayla in the guiding of this map.

^

Through processing the knowledge that has been given to me, I view this work in a new light. The process of giving back to the community by composting flowers was to renew the cycle of healing. These flowers were presented as a gesture of kindness to support the regeneration of new life through composting.

^

Auckland Flowers 15/03/2019, 2019, koha flowers collected from sites that commemorated the Christchurch massacre in 2019; composted, Trashed As, Corban Estate Arts Centre, Tāmaki Makaurau.

^

In return, accepting the gifts received from Orissa, Ayla and Ngākau becomes another cycle of reciprocity with one’s self. This kindness and embrace of connection informs the continuation of cycles, to compost and renew one’s self with acceptance and deserving to feed Papatūānuku.

Rain and Redemption Begins with Papatūānuku: Tikanga as an Arawhiti and Extension of Self

Ayla Collin

Evaporation. Condensation. Precipitation. The hydrologic cycle is the only teaching of reciprocity I recall of my private primary school education. The process of making rain begins with Papatūānuku. Wai makes its home in whenua, and all surfaces Papatūānuku provides, until it rises and returns to Tāwhirimātea, to Ranginui by the tipu and warmth of familial atua. Our atua demonstrate to us purposeful intent and individual contribution to collectivism.

I am introduced to Java Bentley for this issue of Correspondence. Java’s mahi toi centres hangarua (the process of recycling), onepōpopo (compost), and onerua (second life of soil), and is informed by the environment and materials connecting us to Papatūānuku. To hangarua is to bring new mauri or repurpose materials, strengthening relationships we have with one another and the whenua.

What does it mean, the interconnectedness of everything? For me it starts with the everyday relationships we have with ourselves and our surroundings thinking of questions like what does the inside of something mean? What does the outside look like? Java raises these pātai throughout our kōrero, which stems from her artistic practice, and spurs my own examination of tangents spanning two worlds: the Indigenous world, and the ‘other’ colonial world. What does the inside of something look like? I think of systemic conditioning. What looks like education and knowledge but intentionally omits truthful history and Indigenous proficiency? What looks like ‘necessary’, of which its necessity is only to maintain the current unequal distribution of power?

Java selected five kupu she nurtured within her practice and physically embedded them into her final masters’ exhibition, Hei whare onerua, 2023, written onto the wooden structure which was later composted. These kupu speak a collective volume: ‘Papatūānuku’, ‘whakapapa’, ‘new mauri’, ‘kaitiakitanga’, and ‘manaakitanga’. My immediate response, a reciprocal koha to Java’s guiding tikanga, is to offer ‘whanaungatanga’ and ‘kotahitanga’. I’ve been fixated on these positions since the October escalation of genocide in Gaza. I see them as necessary to extending manaakitanga and kaitiakitanga to support whānau Falastini. Engaging with Java’s mahi, I wonder, can we show impact and dependency through a cycle? Like hangarua, like reciprocity?

Orissa, Java and I discuss what resonates for us across each of our contributions to this collaboration. We build this piece together with our respective offerings, we have parts to play—like compost; we have foundations to build upon and strengthen, dependencies, needs, and reliance. Hangarua, onepōpopo, and onerua represent future—whenua foundations aren’t for nothing. Resistance is not for nothing. Hangarua repurposes for new, onepōpopo to feed onerua. The living are biologically equipped for mokopuna, for whakapapa. Our contribution is to future.

Edward Said once described himself as “an extreme case of an urban Palestinian whose relationship to the land is basically metaphorical”.[1]

I am an urban Māori whose relationship to the land was once metaphorical. But now I know the tangible relationship I have with the whenua I whakapapa to. I find increasing comfort and identity in physical whenua practices like onepōpopo. What would our world look like if the human population nurtured a reciprocal relationship with the land?

During the interview “On Palestine: An Open Conversation with Noura Erakat”, Noura centres land as Palestine’s cause and future. Connecting land dispossession and liberation, she notes that solutions for Palestine are articulated within a political equation of land and resource competition determined by power. Recognising how this reduced her own conception of a future for Palestine to the same political parameters, Noura engages in what she terms ‘Palestinian Futurism’, and asks “what happens when we discard sovereignty and think about our relationship as a relationship of belonging, which is infinite? In that relationship of belonging, is a responsibility.”[2]

I am an urban Māori whose relationship to the land is infinite, and I want to look beyond ‘sovereignty’. This word was established by and for those who dispossessed us of our own reo, and our relationships with our land. When I think of an Indigenous future, I think of ka mua, ka muri, our notion of walking backwards into the future. Beyond and before sovereignty ceded or maintained, remains mana whenua. Regardless of the politics of the day, mana whenua sustains beyond the inequitable and inaccessible conversation of Western imposed constitutionalism. It is our relationship to our land that determines mana whenua.

What does it mean, the interconnectedness of everything? Please consider this explanation:

Whenua.

I am an Indigenous mother living a conflicting existence. I don’t want to contribute to the ‘other’ world. I choose our Indigenous world, to shift my contributions from the malevolent empire towards earthly benevolence. Ngau te puku. Hunger pangs. My appetite for whenua has increased since the conception of my first pēpi, intrinsic (I am sure) to being an Indigenous mother. It’s the hypervigilance of being a mother that helps me recognise two tangible catalysts that have quashed any hesitance to abandon the ‘other’ world: genocide and Kauae Raro.[3]

In January I facilitated a Kauae Raro wānanga for Wairarapa Māori education providers. Kauae Raro builds communities with whānau and a collective of artists. They amplify their experiences for others so we too might encounter sensational shifts from assimilation to whakapapa, the dance of decolonising and Indigenising. So we too might be affected by whenua pleasures. Colonial rhetoric has permeated our perspectives and disfigured the significance and collective contributions of our atua, in much the same manner as our whenua. I mihi to Kauae Raro here as they are a community and catalyst for a ‘return to whenua’ that reconnect us to our primordial mother. Java’s practice similarly centres our relationship with whenua and is underpinned by tikanga. Ngā wāhine with the no frills whenua approach.

I consider how the ‘other’ world also centres Papatūānuku: imperialism, colonialism and capitalism requires separating us from her to continue the relentless exploitation and commodification of her. She is objectified, ‘valued’ in a manner that is antithetic to Indigenous imperative. The mana of whenua is subjugated and oppressed, mirroring the treatment of its people.

I do not profess sufficient knowledge of Palestinian whenua, its history, and all it has endured, nor the people who make homes there. I simply know Zionism is a settler-supremacist ideology purposely decimating an entire people and their land, an ideology fuelled and funded by imperium maintained by extractivism under the guise of necessary intervention and peace facilitation. Routine empire maintenance.

I’ve found transitioning from one world to the other slower than I have patience for and harder in principle than I thought it would be. Understanding the multitudes of intersecting privileges I possess, and wanting to exist with reciprocity, the pātai remains for me—what is my contribution? When settler-colonial violence presents genocide, domicide, ecocide, and all its forms of oppression, we must find all the ways to oppose it. Our decisions have impacts we must be accountable for, choose a world and then your contributions. Our collective future depends on our shared relationships with Papa and each other. Reciprocity is the salve.

Java questions, While we continue to fight for the resources that can enable us to support everybody, what ways can we contribute? Whakawhanaungatanga with Java and absorbing her mātauranga has been a restorative experience. Java’s upholding of tikanga throughout her practice is an extension of her as wahine Māori and fafine Sāmoa. Java describes conducting all we do through tikanga as underpinning her practice. Tikanga is sometimes overlooked as mere protocol when it is also an invaluable tool to guide our responses and inform decision making. What would matua Moana do? Moana Jackson describes tikanga as: "a values system about what ‘ought to be’ that helped us sustain relationships, and whaka-tika or restore them when they were damaged. It is a relational law based on an ethic of restoration and seeks balance in all relationships, including the primal relationship of love for and with Papatūānuku. Because she is the Mother, we did not live under the law but rather lived with it, just as we lived with her."[4]

Tikanga is relational and responsive. As an arawhiti and extension of self, tikanga is a way of bridging to other people. As an arawhiti, tikanga facilitates a reciprocal pathway of contribution exchange.[5]

Java describes wanting to gift her mahi toi to Papatūānuku, I saw the life force of my mahi toi to be renewed in the whenua as more significant than its current form. I’m lucky to know Java. Tangata whenua maintain the highest regard for Papatūānuku. We are neither dominant or separate, we are in fact dependents, and we reciprocate to her accordingly. Her permanence is protected and maintained through tikanga me taonga tuku iho. ‘Permanence’ is a kupu that has kept me afloat since October during prolonged periods of irrepressible rage and depression, falling hard and fast into bewilderment at the severity and reality of global settler-colonial violence.

Those of us who believe in a future for Palestine assert the permanence of Falastini as tangata whenua of their lands, mai te awa ki te moana. Permanence for Palestine is a mihi to the unequivocal resilience of Falastini in the face of genocide, acknowledging it is the might of Falastini that has served as a karanga to all humane beings to politicise, radicalise, organise, and mobilise on a global scale. We are changed forever.

What is achievable, practical, and tangible decolonisation in action? Where do we even begin? The answer is everywhere, in the choices we make. What Noura suggests is to consider "where are you? Who are you? And what is your capacity? And then the sky’s the limit of how it is that you are going to manifest your agency and solidarity."[6] We each decide the greatest way to enact our agency.

Tangata whenua are facing the next mutation of systemic racism. When we demand recognition as tangata whenua, we must uphold this standard for all Indigenous peoples. We fight for the same recognition, rights, and reasons. We are connected by whenua and wai, not separated by it. Moana lay atop Papatūānuku. She is Miss Worldwide, she is Palestine too.

It feels appropriately simple to suggest whenua as the interconnectedness

of everything, and tikanga to be our starting point. I frittered away in a pit for six months trying to reconcile two irreconcilable worlds. I made my choice: I choose whenua and tikanga, and I choose future. Palestinian rangatira and friend, Nadia Abu-Shanab in thinking about “the destruction, and the antidote” regarding the genocide of her people and rapacious governments like our own, says, “The purpose of genocide and silencing, and the many tactics used against us, is for us to see only finality. They destroy to underscore futility. To precipitate resignation.”[7] We must actively work towards the future we want, especially when we begin to think it is over. It is not over.

There is no consolation for genocide, though I hope there is a salve in reciprocity. Papatūānuku receives our tīpuna who become beloved whenua to nourish māra and olive trees, and create foundations for mokopuna, for future. Palestine will be free.

Passages from 'Let me rot in the ngaahere' (2024) by Te Atarua Davis (Waikato Tainui).

Bleach my bones, my wheua

In beams of Te Raa

Bake them into the whenua

Like the rest of my iwi

...

Drink up my wairua so that I might

descend all the way to Rarohenga

Koha my body to Papatuuaanuku

Let it rot

Make me tuupuna

Note: Throughout this essay are quotes by Java Bentley, recorded from conversations and email exchanges, identified in italics.

1. Said quoted by Naomi Klein in ‘Let Them Drown: The Violence of Othering in a Warming World’, London Review of Books, Vol. 38 No. 11, 2 June 2016. https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v38/n11/naomi-klein/ let-them-drown

2. Noura Erakat, Céline Semaan, ‘On Palestine: An Open Conversation with Noura Erakat’, Slow Factory, 2023. https://slowfactory.earth/readings/on-palestine-an-open-conversation-with-noura-erakat/

3. Kauae Raro Research Collective was founded in 2019 dedicated to researching and sharing mahi looking at whenua as an art material, a component of ceremony, for personal adornment and as rongoā. Kauae Raro are focused on the retention and promotion of mātauranga Māori around whenua. Their collective and community of whenua artists continues to grow.

4. Moana Jackson, ‘Where to next? Decolonisation and the stories of the land’ in Bianca Elkington et al., Imagining Decolonisation (Wellington: Bridget Williams Books Ltd, 2020), p140.

5. Serendipitously both Java and I have conceptualised arawhiti of and to whenua independently of each other. Java’s Mata-onerua (2024) utilised materials from her kāinga in Tāmaki Makaurau as koha to Whakatū in the form of compost and she has shared her perspective of hangarua as tikanga, saying Bridging across the motu and the gifting of compost from my kāinga to Whakatū was an intentional act of gratitude, connection not confiscation.

6. Noura Erakat, 2023.

7. Nadia Abu-Shanab, personal Instagram post (21 April 2024 @nadiarhiannon_as).

Colophon:

Correspondence 3.2

July 2024

ISSN 2744-7529 (Print)

ISSN 2744-7537 (Online)

ISSN 2744-7545 (Sound recording)

Designed by Erin Broughton

Printed by Allied Press, Ōtepoti

Published by The Physics Room, Ōtautahi

Correspondence publishes pairs of works for the page and ear as openings into and through artistic practices and relationships. You can also access Correspondence as a digital publication including audio editions of each contribution and downloadable PDFs and EPUBs at www.physicsroom.org.nz/publications.

Correspondence was established in 2021 by Hamish Petersen. This issue is edited by Orissa Keane with assistance from Abby Cunnane, Jane Wallace and Amy Weng, supported by the whole TPR staff: Joy Auckram, Honey Brown and Chloe Geoghegan.

To contact the publisher, write to physicsroom@physicsroom.org.nz.

Thank you to all of the contributors and collaborators for Correspondence 3.2.

The Physics Room is a contemporary art space dedicated to developing and promoting contemporary art and critical discourse in Aotearoa New Zealand. The Physics Room is a charitable trust governed by a Board of Trustees, and works within the takiwā of Ngāi Tūāhuriri.

© 2024 The Physics Room and contributors.