Ruby Chang-Jet White and Steven Park

Yawning at the Fray

26 Oct — 08 Dec 2024

Yawning at the Fray is an exhibition by Ruby Chang-Jet White and Steven Junil Park that contends with migration, lineage, grief and healing. Drawing on Chinese postpartum customs and her experience of becoming a mum, White’s sculptural installation and meal service is an echo and a calling, to motherhood, ancestry, and the implications of creation. What has been inherited? What will be passed on? Through silk hangings dyed with locally-grown organic indigo, reworked heirloom silver, and objects that transmute Korean folk traditions, Park’s work offers craft and community as modes of reconciliation with family and heritage–alternative legacies that are hopeful for the future.

There’s something sinewy–chewy, even–to the title Yawning at the Fray. It invokes a deep bodily impulse, and the coming apart at the edges of things. This oscillation between materiality and intuition is the core of this exhibition. It is a title that suggests passing between physical and spiritual states, and acknowledges how eating, making and caring provoke this transition.

回口 (the reply) is the first work White has made since having a baby. The feelings and processing that the postpartum period has called forth underpin this sculptural rug. Informed by White’s relationship with her parents, her Chinese-Malaysian ancestry, and becoming a mother to a daughter of her own, 回口 (the reply) is an expression of White’s efforts to care and be cared for.

The rug is soft and invites you to sit or lie on it, and look into the object at the centre. Tactile chains are fixed around the outside, involving touch and play as modes of learning. White was thinking about how babies and young children are often overlooked in a gallery context. This materiality compels the conversation about parenthood to take place from the perspective of a child’s senses. Two drifting-reaching figures, one bearing a child, compose an ouroboros, the helix of DNA, an earth-bound realm attempting to make contact with the otherworldly. Looping around each other, they attend to reciprocal intergenerational dialogue and memory, always circling back on themselves.

In the centre of the rug is a hand-built ceramic piece. Made as an automatic drawing, the words, built-up forms and flakes of shell and sea glass are markings through a life. White describes this ceramic as a loose meditation on the tabula rasa, the idea that we are all born as blank slates upon which experiences and emotions are mapped to forge the self. Behind cut-out panes, a quiet video work plays. It is filmed through the windows of White’s home, looking out into the world. This is the same house that White grew up in and where she is now raising her daughter, who moves in and out of the image. Most of the video is obscured by the ceramic frame but the shifting fragments that can be viewed act as openings into different rooms of a heart, a home, a life.

Dimensions of relation and separation from her Chinese-Malaysian heritage, and the forces that have made White who she is, exist here as a whirlpool of matrescence. White says “becoming the mother to a daughter of my own has become a deeply profound mirror into why I nurture the way I do, the insecurities I have around connection and the ways that I fail to love effectively (to myself and others).” The Mandarin characters for “help me” are subtly shaved into 回口 (the reply), like a whisper. For those who cannot read Mandarin, including White, the characters become pictorial. In this instance, language is not a tool of communication but makes her ancestors visible. “Help me” is a demand for healing that goes both ways. White acknowledges the difficult implications of asking for healing through parenthood, and the grief that is reopened too. 回口 (the reply) approaches something close to acceptance of intergenerational shortcomings that are inevitable in being a parent and a child.

The failure of language to connect fully to one’s parents or culture across the chasm of time and place also guides Park’s commitment to craft. Activities like stitching, singing or carving are enduring parts of a shared human lineage. Park holds a deep belief that communing via these practices might reconcile some of the things that speaking cannot.

Gazing at two horizons is a two-headed duck carved out of elm from Park’s back garden. Ducks are a familiar symbol of prosperity in Korean folk traditions. A pair is often gifted by close relations at weddings as a wish for a long and happy marriage; or, when elevated to sit atop a wooden pole as a sotdae it wards off evil spirits and brings auspicious tidings to the community. Gazing at two horizons references both of these customs, and also recalls the belief that ducks are messengers between the physical and spiritual realms, arising from observations of their migration patterns.

These ducks, bound together by a wooden body, are unable to look directly at each other but only in opposite directions. The two horizons that they gaze at are that of Korea and Aotearoa–the place where Park was born, and the place that is now home. Like the ducks, these places are inextricably linked but struggle to see eye to eye, though they remain one body, one spirit. The geographic distance between Aotearoa and Korea is underscored by an equally vast cultural distance. Yet, sotdae are also beacons of goodwill and hope. Pitched at the perimeter of the gallery, Gazing at two horizons describes the strength of inheritance as much as its impasses.

Hanging by a strand of hand-twisted silk cordage dyed with locally grown, organic indigo is a small silver bell, titled Sing me the songs you used to sing. This bell is cast from fine silver melted down from utensils that were given to his parents and grandparents as gifts for their weddings, following an old tradition, that they then passed down to him. Though made into a new form, they still hold the memories of their provenance, symbolising these connections that span generations. Park holds these stories within himself: his body and his life are testaments to those who came before him. In casting Sing me the songs you used to sing from this heirloom silver, Park transforms the energy held within into something new.

A house built from inherited bricks uses a similar material translation. Two silk organza window hangings–one saturated in vivid blue indigo, the other a slightly softer hue–are suspended in the gallery’s windows. The pieces of silk cut out from one hanging are used to create the surface of the second. On each, concentric layers, cut freehand and egg-shaped, intensify and recede like cosmic portals. A house built from inherited bricks confronts the parts of our parents that constitute our selves. With what is inherited, we make anew; these parts crystallising in a distinct way.

There is indigo throughout Yawning at the Fray. Grown out in Lincoln and processed into pigment and dye by Park’s friend Gina Russell, the indigo species (Persicaria Tinctoria) is not endemic to Aotearoa, but to East Asia. For Park, the experience of using materials grown locally by a friend has been transformative in deepening his sense of rootedness in this land. Cultivated alongside a rich community, the indigo used in Yawning at the Fray represents the seeds of hope and connection planted in the fertile soil of craft, as a vision for the future.

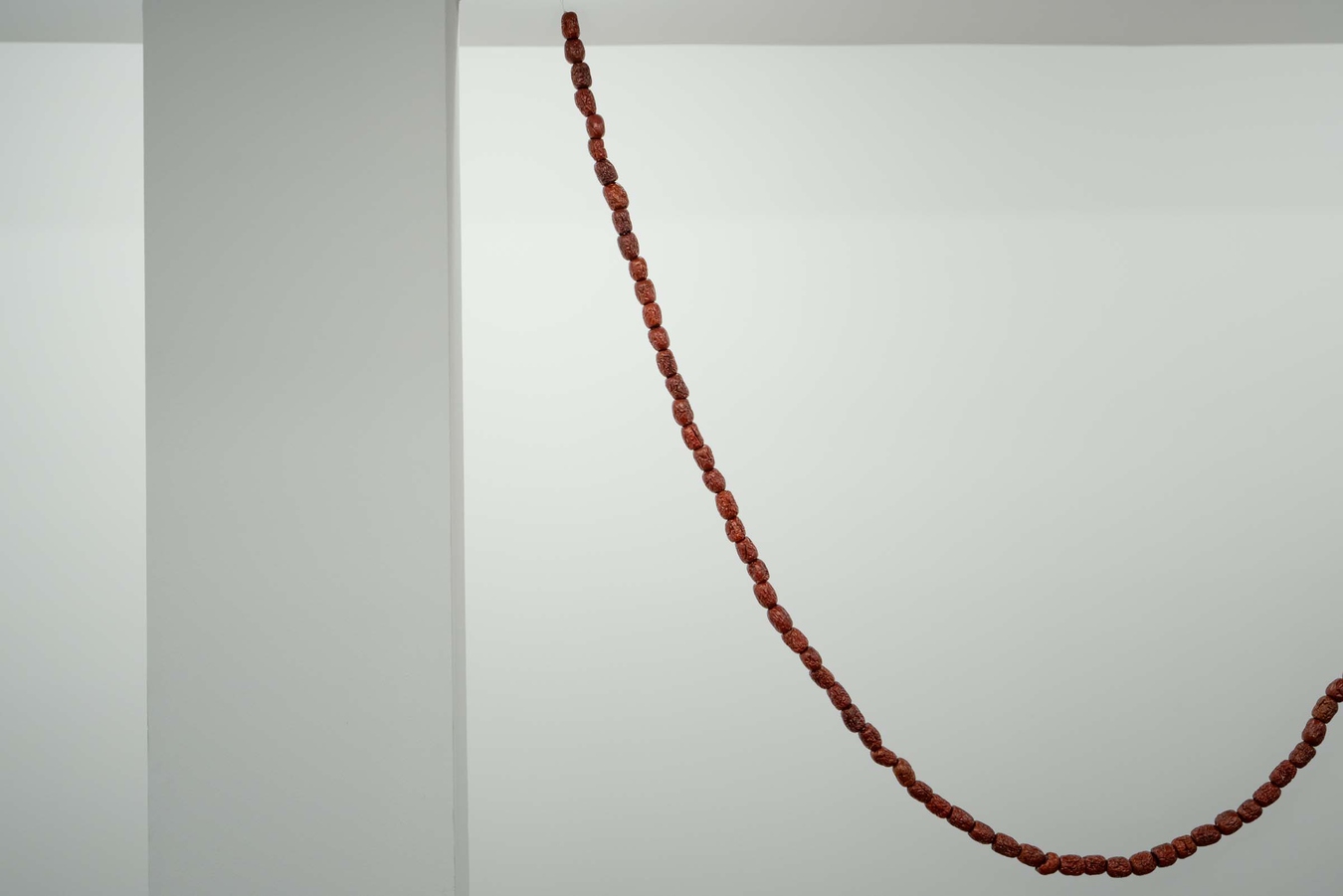

Strips of indigo-dyed cotton and linen also wrap the parcels of food that White prepared for Other tongue 餓 ghost kitchen. The meals cooked for Other tongue 餓 ghost kitchen are not present in the gallery; orders are collected on the first day of the exhibition. This project is an expression of White’s ongoing exploration of food and cooking as a gateway to more intuitive versions of the self and its desires. Delivering Other tongue 餓 ghost kitchen as an event located within the week of install expands the way these concepts are engaged with, into the physical acts of cooking and eating. White developed Other tongue 餓 ghost kitchen as a postpartum takeaway food service for healing birthing or menstruating bodies. Three dishes–擂茶 Lei Cha, 鸡鸭三米粥 Chicken and duck three rice congee and 猪脚姜 Hakka braised pork–are inspired by the 坐月子 Zuo yue zi postpartum cuisine (specifically Hakka dishes) and the philosophy behind Chinese medicine. The ingredients in them are intended to bring warmth back into the body and extract any toxins. Although this is a practical reason for eating these specific foods during the fourth trimester, the importance of ritual is also foregrounded in Zuo yue zi custom, as a time when parent and child are forming an important bond and preparing to reenter the world. White’s interpretation of these meals has adapted to her own taste and experience and an awareness of the primordial aspect of eating and feeding in tune with the body’s needs. Remnants of an important ingredient in the congee, jujubes, are strung up as a garland above 回口 (the reply). These repeating jujube arcs are an echo of the Other tongue 餓 ghost kitchen and the restorative properties that guided White’s menu.

Yawning at the Fray affirms that healing and comfort are possible through deeply connected craft and food-based practices. Through White and Park’s work, the challenges of speaking to those who came before as an honest version of oneself are not erased, but folded into a perpetual chain of legacy.

*****

Other tongue 餓 ghost kitchen

Yawning at the Fray includes Other tongue 餓 ghost kitchen, an exchange and collaboration by artist Ruby White. Between The Physics Room (Ōtautahi) and Bus Projects (Naarm), White has developed this takeaway food service, offering nourishing meals that honour birthing, menstruating bodies and bring comfort to those looking for some inner healing.

Preorders are now open until Friday 25 October!

*****

Ruby Chang-Jet White is a Chinese-Malaysian Hakka and Pākehā artist who works predominantly with food and ceramics. Using inherited memory, craft and tacit knowledge, to reflect on and explore histories, intimacy and bridging worlds. More recently she has become more focused on how food can be used intentionally to cultivate spiritual and bodily empathy. She became a mother last July.

Steven Junil Park is a Korean-born multi-disciplinary artist based in Ōtautahi. His practice explores the potential of the handmade to express identity and understand the human experience, producing clothing, textiles and other functional and craft-based objects.

Yawning at the Fray and Other tongue 餓 ghost kitchen have been developed in collaboration with Bus Projects (Naarm).