Sophie Bannan and Joshua Harris-Harding

A Wandering Thing

08 Aug — 15 Sep 2019

Exhibition preview: Wednesday 7 August, 5:30pm

Exhibition runs: 8 August – 15 September 2019

Exhibition talk with Joshua Harris-Harding & Jamie Hanton: Thursday 8 August, 12pm

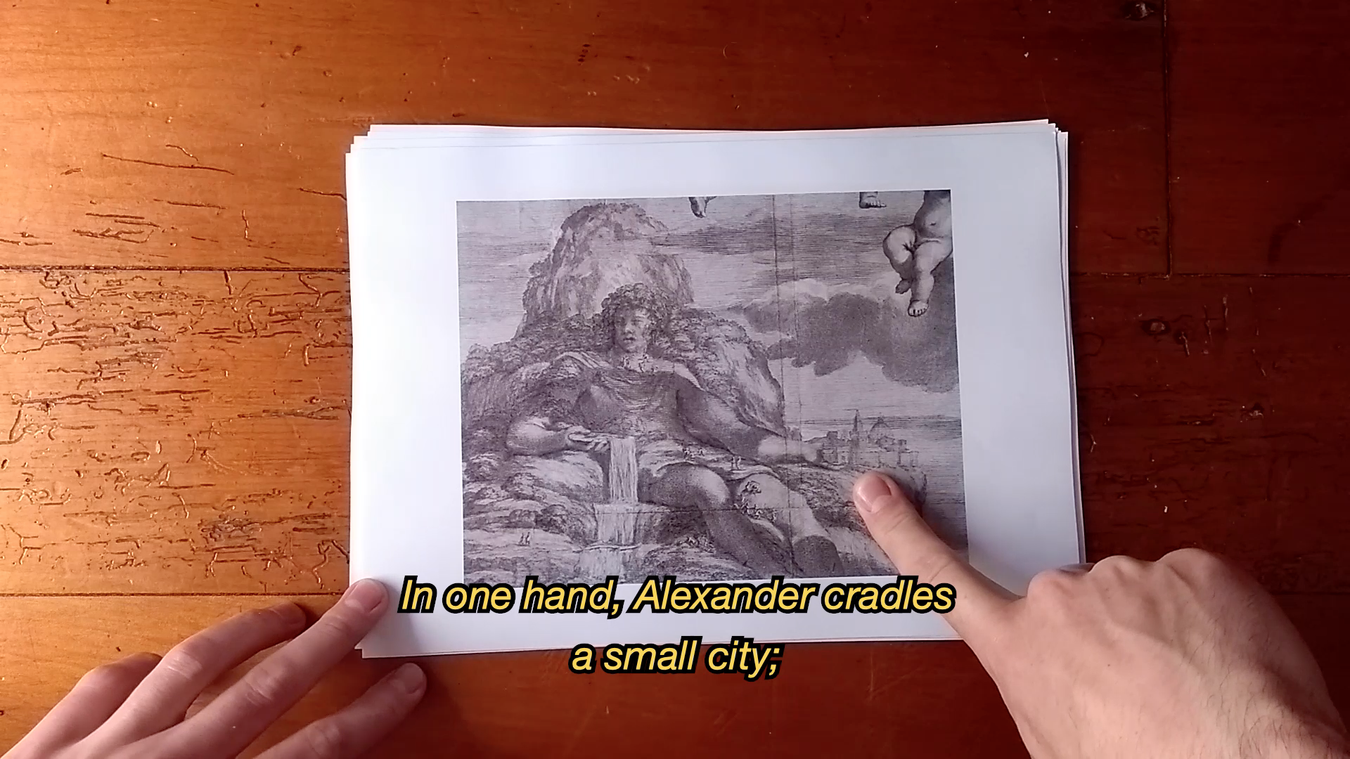

Dinocrates’ plan to carve a gigantic likeness of Alexander into the flank of Mount Athos never eventuates. In this plan, Alexander cradles a small city in one hand, and a pitcher in the other, from which a river will flow into the sea.

The main effect of abstracting water from collective guardianship is to conceal the link between the source and its consumption. The disparity between end use and control is exacerbated by the bureaucratisation and scientific professionalisation of water management. Through this arrangement, we are acculturated with the understanding that water is an artefact, distinct from common property.

“I drink from the spring at Cerne Abbas... and get the most vicious cold of my entire life. This particular bug does get me worried... (because) it’s very much a working churchyard now, you can see all these graves above. Though one hopes the water comes from below, you do start thinking, well, it’s probably flowed through a few bodies too. So probably best not to drink from this well!”

The common law (the law established by precedent), imported here from England, does not recognise ownership rights in freely flowing water. Flowing freshwater is classed as publici juris, free for all who can access it – like air and light.

Some sorcerers do boast

they have a Rod

gathered with vows and sacrifice and (borne about) will strangely nod to hidden Treasure where it lies mankind is sure that Rod divine

for to the Wealthiest (ever) they incline

•

Jane is born in a Lancashire poorhouse and arrives in Waiuta as a teenager. Someone initially names the town Waiutu – water/river that gives. Consolidated Goldfields Ltd. take 1.5 million tons of gold bearing quartz and ceases operation when a shaft collapses, closing the mine and ghosting the town.

The first of Jane’s six babies born at Waiuta hospital dies before his second birthday of a chest infection in late autumn. Their weatherboard cottage is uninsulated; newspaper is stuck with flour glue to the inside walls to keep the draft from coming through cracks and is replaced whenever rats have chewed through it. By morning any water left out is frozen, as well as dew on the inside of windows.

Her second baby, born in 1915, is my great grandmother Edna Greta. The first world war has broken out and with it the international gold standard is suspended and exports are restricted, including that of gold.

Her third baby Florence, born at Waiuta hospital in mid wartime, always has a short bob haircut with a sharp fringe covering her eyebrows, from under which she gazes upon her photographer with a thoughtful scowl.

A photograph: a picket gate with peeling paint is open, cutting into the left edge of the frame; from the gate a slightly raised poured concrete path leads almost horizontally through scraggly grass specked with stones, quartz and greywacke, to a weatherboard house with a covered front porch; people on the porch are facing toward the house but looking over their right shoulders towards the photographer, they’re partially obscured by a light flare on the film; a man in a medium toned suit with a neck tie and shiny shoes walks down the path away from the house, left foot forward, he is looking into the camera; ahead of him four girls in two rows, stepping in unison, the modest heels of their right shoes to the concrete, breast buds making small peaks in their short-sleeved white smocks, heads lowered and darkened by the shadow of their narrow brimmed white hats; the girls flank a small dark coffin with metallic hardware, their hands are in white gloves. Florence fell from the maypole in the schoolyard. The maypole stood at the top of a bank running down to the road, so that if you swung high enough and let go you’d land in the middle of Top Road. But by 1928 when Florence falls the schoolhouse has moved, and the maypole with it, so she couldn’t have fallen far, but they say that’s what causes her brain tumour. She dies at home in late spring after her tenth birthday.

--

Sophie Bannan (b. 1989, New Zealand) is an artist and writer living in Tāmaki Makaurau. She co-founded and directed artist-run initiatives Personal Best (Auckland), Strines (Melbourne) and North Projects (Christchurch). Recent texts include catalogue essays for 90 Canon Homeshow, curated by Louise Palmer (2017); and Miranda’s Parkes’ Frances Hodgkins Fellowship exhibition, The Merrier (2017). Recent exhibition projects include Hut for a Sensuous Goldminer, with Daegan Wells, Meanwhile Gallery, Wellington (2018); Stromlo, with Dan Nash, RM, Auckland (2016); Backwater, North Projects, Christchurch (2015); Thinking About Building, (group show curated by Melanie Oliver), The Physics Room, Christchurch (2014); and The Optimists, with John Ward-Knox, Blue Oyster Art Project Space, Dunedin (2014).

Joshua Harris-Harding (b. 1989, New Zealand) is an artist and writer from Tāmaki Makaurau. His research engages with the contingencies of language and the nature-culture dualism through myth, history, and narrative. Recent exhibition projects include Sports, Demo Gallery, Auckland (2018), Inconsolata, with Vanessa Crofskey, RM Gallery, Auckland (2018), Lapidary, Projectspace, Auckland (2017), and contributing text for The River Remains: ake tonu atu, with Olyvia Hong, Artspace (2018).

--

Click here to listen to Art, Not Science Episode 2

In this episode we present two artist talks, one from A Wandering Thing by Sophie Bannan and Joshua Harris-Harding and one from The Freedom of the Migrant by Matthew Galloway.