Correspondence 3.1

Correspondence 3.1 designed by Erin Broughton

Correspondence is a biannual tabloid, publishing pairs of works for the page, web, and ear, as openings into artistic practices and relationships.

Correspondence 3.1 considers artistic practice in the ever-changing context of a climate emergency. With a particular focus on materials, this issue contains contributions by Raewyn Martyn, Isabella Loudon, Melissa Macleod, Claudia Dunes, Hana Pera Aoake, Te Kawehau Hoskins and Alison Jones, and Loulou Callister-Baker.

We hope you'll be able to pick up a copy from one of our listed distribution points below. However, you can also enjoy this issue by downloading the full PDF, by listening using your screen reader, or by listening to the audiobook below.

Please note that the HTML text version of Correspondence 3.1 on this webpage is intended mainly for screen readers. If you're a sighted person, you might better enjoy the thoughtful design qualities of the downloadable PDF and print versions. The audiobook is there for all audiences to provide as an alternative way to engage with the contributions in this issue.

Started by former Writing and Publications Coordinator, Hamish Petersen, Correspondence is a biannual tabloid produced by The Physics Room which explores forms of art writing in Aotearoa. Correspondence 3.1 is edited by Orissa Keane and designed by Erin Broughton.

Contents

Orissa Keane, Conversations about the weather can no longer be regarded as small talk

Raewyn Martyn, Circles & Lines

Material costs: A conversation between Isabella Loudon, Melissa Macleod and Orissa Keane

Claudia Dunes, documentation from Proposition For Future Pet, 2020

Hana Pera Aoake, Meeting the Lake

Te Kawehau Hoskins and Alison Jones, an extract from Non-Human Others and Kaupapa Māori Research

Loulou Callister-Baker, Melancholic Mellonella

Contributor biographies

Distribution

These are the sites who will be holding stacks of Correspondence 3.1 for free distribution to the public (limited supply):

Ōtautahi

The Physics Room

Ilam School of Fine Arts (in 2024)

Ōtepoti

Blue Oyster Art Gallery

Dunedin Polytechnic School of Art (in 2024)

Te Whanganui-a-Tara

Enjoy Contemporary Art Space

The Dowse Art Museum

Massey University, Wellington CoCA Campus (in 2024)

Tāmaki Makaurau

Corban Estate Arts Centre

Fresh Gallery

Elam School of Fine Arts (in 2024)

Samoa House Library

And...

RAMP, Kirikiriroa Hamilton

Pātaka Art + Museum, Porirua

The Suter Art Gallery, Whakatū Nelson

Australia

RMIT, Naarm

Melbourne Art Library, Naarm

VCA, Naarm

Details

Correspondence Volume three, Issue one

Published November 2023

ISSN 2744-7529 (Print)

ISSN 2744-7537 (Online)

ISSN 2744-7545 (Sound recording)

Edited by Orissas Keane

Designed by Erin Broughton

Printed by Allied Press

1000 copies of a 32pp tabloid on 52gsm newsprint

Featuring contributions by: Raewyn Martyn, Isabella Loudon, Melissa Macleod, Claudia Dunes, Hana Pera Aoake, Te Kawehau Hoskins and Alison Jones, and Loulou Callister-Baker.

3.1: CONVERSATIONS ABOUT THE WEATHER CAN NO LONGER BE REGARDED AS SMALL TALK

Conversations about the weather can no longer be regarded as small talk

Orissa Keane

Weather often crosses different parts of speech. It is a noun, indicating climatic conditions. As weathered, it is an adjective that describes an altered appearance, wear due to exposure. And, as a verb, to weather, it can mean to make it through an event—to endure, though not necessarily resisting change. We are feeling the effects of the weather. We are weathering, becoming weathered, while also continuing on. What shelters and what frameworks must be constructed, not to withstand the weather, but to change with it?

Correspondence 3.1 considers artistic practice in the ever-changing context of a climate emergency. With a particular focus on materials, this issue contains contributions by Raewyn Martyn, Melissa Macleod, Isabella Loudon, Claudia

Dunes, Hana Pera Aoake, Te Kawehau Hoskins and Alison Jones, and Loulou Callister-Baker.

Stemming from some themes of her doctoral dissertation, Raewyn Martyn’s contribution, Circles & Lines, explores tools for living with and changing with the climate in the context of global capitalism and socio-economic thinking. Citing Arlie Russell Hochschild’s allegory of The Line and what it means to think in linear terms about an individual’s access to collective resources, Raewyn proposes that climate change be met with big-hearted action, reminding us that art has a way of imagining beyond immediate realities.

I have been thinking a lot about guilt and its function in artistic practice, particularly in making material choices, and beyond that, in everyday life. But guilt is also sticky, attaching itself to certain things, sometimes prematurely or without justification—still, our aim should be to pre-empt the action which causes guilt, shouldn’t it? In Material costs: A conversation between Isabella Loudon, Melissa Macleod, and Orissa Keane, we discuss imperfect outcomes, personal best practice standards, and institutional and social pressures. We note the internal conflict artists sometimes face in bringing more matter into a world that already feels full of things. In response to this, I want to say here that contemporary art is necessary: it exists as a way to make sense of our surroundings, consciously or not. It is also unique as a record of current times. Artists will always work with what they’re interested in, and what is available to them, meaning that the work is inextricably embedded in social and cultural context.

The larvae of the Zophobas morio beetle are better known as superworms. Some insect larvae possess a particular enzyme in their gut microbes which can break down polyethylene products, including polystyrene. Even though news articles say that nobody is intending to unleash dozens of square tonnes of larvae into a rubbish tip, rather scientists will try to find a way to replicate the enzyme which breaks down the complex carbon chains, bypassing the worms altogether, I still can’t escape thoughts of a utopic writhing pit.

The superworms became an interest for artist Claudia Dunes in 2020. Claudia’s resulting project Proposition For Future Pet was shown as part of her final MFA exhibition. For about four months Claudia housed a colony of superworms within a repurposed fish tank, caring for them and adjusting their environment as she began to better understand their needs. Claudia’s project proposes that we proceed with affection and empathy towards these incredible critters and others, that not only live with but live off our waste. You’ll find documentation from this project in this issue.

Galleria mellonella, waxworms, which metamorphose into wax moths, also eat polystyrene when they’re given no alternatives. Imagining the possibilities of waxworms, Loulou Callister-Baker’s short story, Melancholic Mellonella, provokes us to consider a gruesome solution to eliminating the microplastics which inevitably circulate in our bodies.

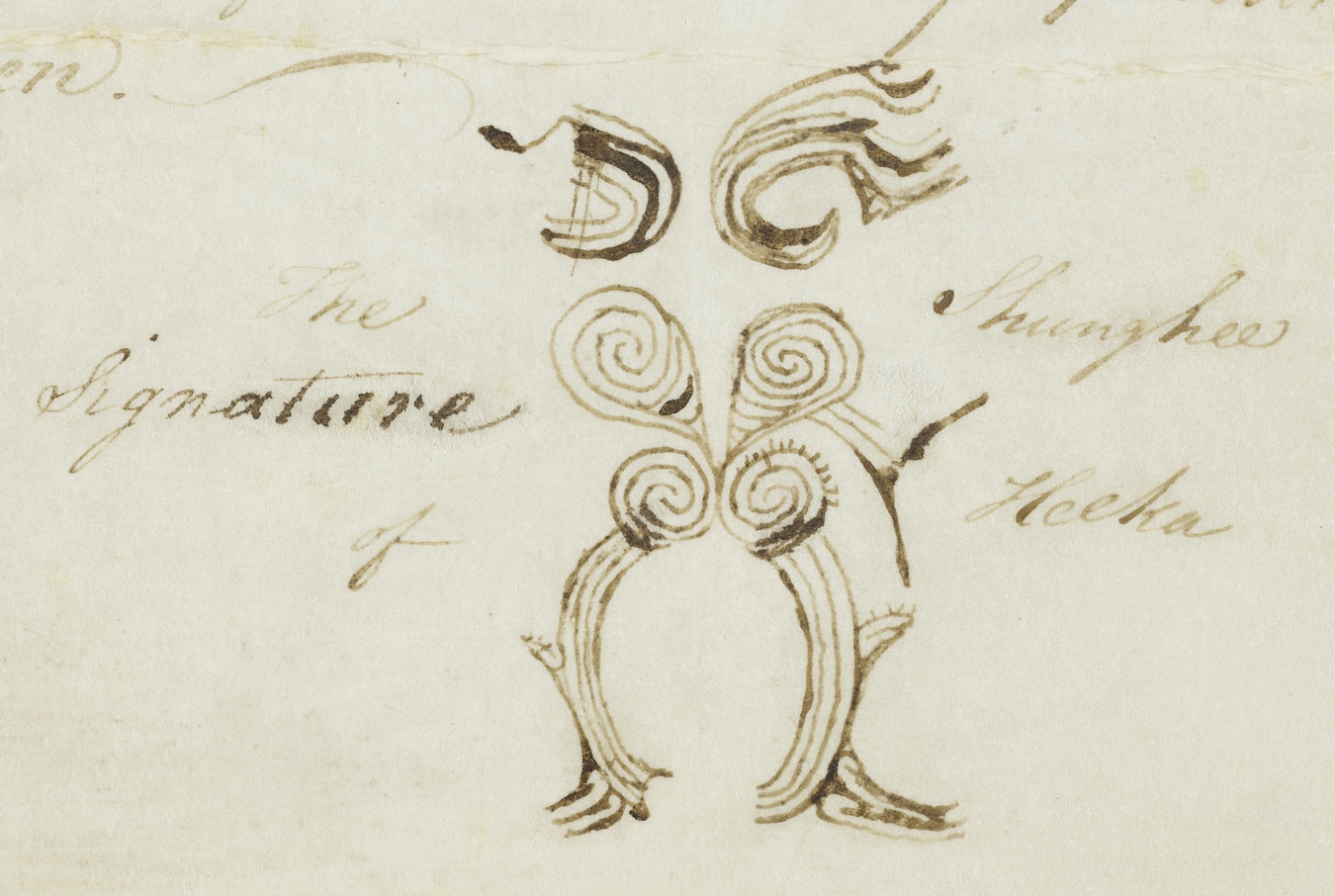

In Meeting the Lake, Hana Pera Aoake writes in acknowledgement of Te Kawehau Hoskins and Alison Jones’ Non-human Others and Kaupapa Māori Research. The chapter was originally published in Critical Conversations in Kaupapa Māori, in 2017, by Huia Publishers. Working from a Kaupapa Māori foundation, Te Kawehau and Alison attempt in this chapter to engage their research more directly in consultation with non-human entities, consulting Hongi Hika’s moko on the 1819 Kerikeri land deed, and focusing on what the moko mark, itself, might have to communicate.

This essay is one that Hana has been returning to often. Here, we republish an extract of this chapter alongside Hana’s reflections on the clarity and generosity of Te Kawehau and Alison’s words. The title Meeting the Lake nods to a quote by the late Ahnishinahbæótjibway thinker Wub-e-ke-niew (found in the footnotes of Non-human Others, and cited by Hana), referring to all things being in equal relation to one another, as opposed to a subject/ human acting upon an object/thing: “a person ‘meets the Lake’ rather than ‘goes to get water’”.

The title of this issue, Conversations about the weather can no longer be regarded as small talk, is something I’ve been thinking about for a long time. But the reality of the sentiment only sunk in after the extreme weather events early this year. Severe flooding in Tāmaki Makaurau in January 2023 preceded February’s Cyclone Gabrielle, the tropical cyclone whose destruction is still being—and will continue to be—felt broadly across Te Ika-a-Māui. Last month in Ōtautahi we all received a weather alert direct to our phones for severe winds. That familiar heart-sinking sound. With El Nino coming this summer I don’t look forward to forecasts for warm weather in Ōtautahi, as with it will inevitably come the hot dry Northwest wind.

As an editor I hope that you find the contents of this publication new and of interest. I also hope that you find some comfort in knowing that it is compostable.

Circles & Lines

Raewyn Martyn

Psychologists from the Climate Psychology Alliance along with activists from groups like Greenpeace have been suggesting that all humans need to feel the enormity of climate change but resist defeatism.[1] For many people, the acceleration of climate crisis has led to feelings of paralysis, when we actually need to venture into this reality with our hearts open to survival.

Once we make the cognitive and emotional leaps of imagination that enable radical hope, it’s more likely that we’ll embrace both individual and collective action and be less likely to sit back and let the impacts of climate change be felt unevenly.

There’s a romanticism within this resistance to defeat. In art and literature, Romanticism is visible in the imagery of adventure, and brave-hearted individualistic behaviour that invokes a heroic past. We can’t ignore that this heroic past is tied to the frontiers of colonisation and this behaviour doesn’t necessarily lend itself to rational collective action. However, the 19th century Romantic attitude also influenced the intersubjective visions and emancipatory politics of Dada and Surrealist artists, who complicated the narrative of the individual, and offered open-hearted leaps of imagination.[2] The historical resonance of that moment reminds us how art has the capacity to envision alternative realities, allowing us to imagine ways of living and loving beyond what feels rationally possible in the present. In doing so, art contributes to the project of building new political imaginaries.

In politics, the allegory of The Line[3] has been used to illustrate how White working-class voters in the United States have internalised the image of a line in which they are waiting for their turn to receive a fair share of public resources and the financial and social advantages of capitalism—jobs, housing, health services, etc.[4] The people in The Line aren’t necessarily expecting huge material gains, but simple middle-class wealth and basic social services. Despite ongoing claims of American exceptionalism, this progression and access hasn’t ever been available to everyone—and it has become even harder to access over the past fifty years. The Line comes into play in emergency situations too. And has become important over the past decade as extreme weather events and the need for disaster relief has increased.

When one’s sense of access to resources is imagined as linear, it becomes easy to perceive anyone else entering that line as decreasing your own access. At the same time it becomes easy to perceive other concerns or shared challenges as distractions and slowdowns of The Line—regulation and collective action on climate change become an affront to your personal rights of progression, for example. Meanwhile, recovering from an extreme weather event, you might find yourself back in another line, awaiting the emergency and rebuilding support that you need because of global heating.

The Line allegory was developed by Arlie Russell Hochschild, a sociologist who has researched emotional drivers within politics. She believes that working-class people who are attached to the idea of The Line and end up voting against their own best interests due to overwhelming resentment are exercising anger but also huge underlying grief. Hochschild also theorised the concept of emotional self-regulation as a form of service work known as emotional labour. Reading her work on emotional labour, I started thinking about how different linear and circular allegories might influence the processes of emotional self-regulation that emerge during crises. Images of lines and circles both generate and temper expectations of how wealth and resources are distributed.

Waveforms

It’s really hard to change an internalised image once it has a grip on your psyche. The thought experiment of imagining alternative imagery is an important one right now. In 2011, Occupy Wall Street attempted to use data visualisation through typographic representation of The 1%, raising consciousness of unequal distribution of wealth and power in a way that could change our sense of how wealth is concentrated in the current system. In turn, this concentration undermines distribution via any imagined line.

Astra Taylor creates an image of capitalism as an ongoing wave of destruction, inciting scarcity and precarity in an age of insecurity where capitalism is an insecurity-generating machine.[5] In physics, waves distribute energy or force with varying degrees of impact and duration and can be represented as fluctuating lines. Taylor’s waveforms of capitalist destruction might also be represented in this way, and experienced as cycles of interference within The Line. Similar ideas emerged in the 1940s, Joseph Schumpeter wrote that capitalism works through gales of creative destruction—it necessarily destroys wealth to create new wealth.[6] Following this logic, defeatism within the climate crisis would allow the gales of creative destruction to play out within communities who don’t have the resources to adapt.

There’s a bunch of scholarship being done around these ideas now, and I picked up on the links between these terms while I was listening to a podcast in the studio recently. NPR guest Jack Beatty noted that two generations of Americans have experienced these increased gales of creative destruction since the 1970s. Contemporary references to Schumpeter’s meteorological metaphor focus us on the extreme weather created by capitalism in both an ecological and socio-economic sense. Beatty was discussing The Line and the impacts of perceived scarcity to understand the psyche of voters in upcoming elections, but I think it also illuminates the need to create conditions and visions for sharing resources differently in the face of climate change and the pandemic, and in everyday struggles.

Limits of empathy

In Aotearoa, people coming of age in the late 90s and first decade of the 2000s were born during a time of economic restructuring in Aotearoa. Working-class people had been thrown into line with these gales of creative destruction, further entrenching the impacts of colonial capitalism. By the mid 2000s, many young Pākehā artists were experiencing a confluence of anti-colonial and climate consciousness. Land occupations in the 1990s had been live broadcast, and events like the passing of the Foreshore and Seabed Act 2004 and the subsequent protest hīkoi furthered awareness. Conversations about rising sea levels were happening at the same time as conversations about rights to that changing space between high water and low water.

For ‘elder millennials’, our twenties were punctuated by big global and local events like 9/11, and the earthquakes in Ōtautahi. I wasn’t in Ōtautahi during the earthquakes—at 12:51 pm on 22nd February 2011, I climbed under my desk in the offices of Te Kura Pounamu the Correspondence School in Thorndon, Te Whanganui-a-Tara. Over the following hours and days, Wellingtonians looked aghast to the south, self-absorbed by our own tremors, we just hadn’t considered that the big one might happen elsewhere. The spectre of The Earthquake had always been tangible in Te Whanganui-a-Tara because we had all felt the little quakes, they were measurable; the information reported to us by GNS and the media corresponded and aligned with what we each individually felt in our bodies as the earth moved.

On February 22nd, I had a realisation that something felt so intensely in one place could be felt very differently in another— something I had understood in theory, but beyond occasional proximity to violence or accidents, I hadn’t felt it physically before.

The climate crisis had been unfolding for decades, a seemingly imperceptible slow-slipping event. People in positions of power, under the thumb of petrochemical and capital interests, chose not to perceive the deadly registers of atmospheric imbalance—and their voters couldn’t yet feel the impacts physically or economically. Climate change was intangible and distant. In the early 2000s, climate reporting had an air of the unknown future; a projection that didn’t correspond to daily experiences. Until it began to align.

Between 2020 and 2023, people have experienced moments where our personal lives were altered by the biological and economic realities of a global pandemic—the circulation and reproduction of life-threatening viral matter, alongside the accelerating impacts of the climate crisis. In 2020, news of early viral spread hit the airwaves at the same time as our New Year horizons became dusty pink with drift from the Australian bushfires. Moments of personal and collective grief were met with empathy as a necessary part of the emotional processes of social cohesion that allow communities to survive. At the same time, these events exposed limits to that empathy. And, as with climate change, the ongoing impacts of the pandemic have been felt unevenly, with access to vaccines limited to those countries who could afford them.

Circular materialism

As an artist, I have been working with unstable materials and processes that involve reconfiguration and adaptation within particular situations and architectures. This often invites decomposition, but attempts to resist a dead-end collapse. Since 2012, I’ve transitioned from using petrochemical ‘latex’ paints and materials to bio-based ones.[7] Initially this came from a desire for delaminated latex wall paint to have the capacity for rehydration—to become a ‘hydrophilic’ circular material.

My work hasn’t become ‘about’ climate change or the pandemic, but these crises have focused my thinking about the limits of empathy, shaping my use of material empathy in processes of art making; decomposition and composition. There is a ‘biopolymer aesthetics’ that has developed from this—aesthetics in the sense of its root words of feeling and perceiving, beyond the retinal or stylistic. These aesthetics are connected to the plasticity, fluidity, and instability of polymers used in post-war practices where the material innovations of the war industry met consumer markets, including artists like Louise Bourgeois and Lynda Benglis who used both biopolymer and petrochemical polymers.[8]

Thinking through this history in an Aotearoa-based context, I focused on non-Indigenous material practices and asked artist Christine Hellyar how her awareness of land rights and ecological material relations developed over time, and at what point a specific consciousness of human-induced climate change began to influence her work. Awareness of colonial land confiscations and the ecological impacts of capitalism informed her material choices and subject matter while at art school during the late 1960s, and as she began experimenting with latex sourced from a Papakura glove manufacturer.[9] Hellyar sourced latex from the Skellerup gumboot factory in Ōtautahi Christchurch to create works like Flotsam and Jetsum, 1970. Skellerup was a pragmatic choice rather than a conceptual one, but it also registers the dominance of agricultural and colonial capitalism within our ecological and material cultures disrupting romantic notions of unfettered ‘New Zealand’ landscapes.[10] Industrial bio-based rubber production has involved extreme violence that isn’t inherent to the material, it arises in the linear systems of colonial production. This complicates any sense of innocence around bio- based materials and needs to inform transitions from petrochemical material culture. Thinking about non-Indigenous ‘hydrofeminisms’ and climate resilience here in Aotearoa, the iconic material ubiquity of waterproof and water-proud ‘gummies’ repurposed in the form of artworks offers an egalitarian way to move through flood plains.[11]

Notes:

1. Psychologists like Caroline Hickman and other members of

the Climate Psychology Alliance have worked with groups like Greenpeace to raise awareness of climate psychology and to develop community capacity for radical forms of hope within the realities of crises. For further context see: Marks, Elizabeth, and Caroline Hickman. “Eco-distress is not a pathology, but

it still hurts.” Nature Mental Health 1, no. 6 (2023): 379-380. For another viewpoint that embraces defeat as a strategy, see: Thaler, Mathias. “Eco-Miserabilism and Radical Hope: On the Utopian Vision of Post-Apocalyptic Environmentalism.” American Political Science Review (2023): 1-14.

2. Breton published his initial Surrealist Manifesto (1924), in the wake of WWI. Walter Benjamin described the political impact of the Romantic attitude in Surrealism: Benjamin, Walter. “Surrealism: the last snapshot of the European intelligentsia.” New Left Review 108 (1978): 47. Reading Benjamin, it’s possible to argue that the Surrealists offered a Romantic Materialism.

3. Hochschild, Arlie Russell. Strangers in their own land: Anger and mourning on the American right. The New Press, 2018.

4. Here in Aotearoa during the 2023 election campaign, the National Party have successfully invoked and affirmed images of ‘getting back on track’ (not a new national rail service) and on election night Chris Luxon drew loud applause, saying: “in the best country on Earth, you should be able to get ahead”.

These phrases have been used to generate both a collective and individual sense of progress—’get our country back on track’ and a general sense of ‘doing it together’ reflect learning from the Labour government’s ‘team of five million’ and ‘unite against Covid-19’ campaign. And John Key’s 2007 insight that a “socialist streak runs through all New Zealanders”, when these comments were made public via Wikileaks, he explained that this means we are caring, and “have a heart”. In 2023, the questions remain: how are the rail cars structured? And, getting ahead of what and whom? Chapman, Kate. 2011. “Key Admits ‘socialist Streak’ Comment.” Stuff. August 26, 2011.

5. Taylor, Astra. The Age of Insecurity : Coming Together As Things Fall Apart. Toronto: Anansi, 2023.

6. Schumpeter, Joseph A. Capitalism, socialism and democracy. Routledge, 2013.

7. In the USA, water-based petrochemical house paint is often referred to as ‘latex’ and there is conflation and misunderstanding of ‘latex rubber’ and ‘latex paint’. This results from the history of interconnected ‘natural’ commodities and cheaper petrochemical synthetics developed for the war industry and consumer

market. With a postwar surplus of synthetic latex, it became a ubiquitous ingredient in domestic consumer products, from childrens toys, to condoms, to house paint. Kahn, Anastasia Jaquelyn. “Fleshly Specificity and the 1960s: The Latex Objects of Louise Bourgeois, Eva Hesse, and Lynda Benglis.” PhD diss., State University of New York at Stony Brook, 2019.

8. I have largely focused on work made by non-Indigenous women artists working in the United States and Aotearoa New Zealand, using both bio-based and petrochemical materials. Polymer aesthetics of fluidity, reuse and misuse of plastic and skin-like materials are evident in work by Louise Bourgeois (Portrait 1963), Eva Hesse (Aught 1968), Lynda Benglis (Fallen Painting 1968), Senga Nengudi (Water Composition II 1969-1970), and Christine Hellyar (Flotsam and Jetsum 1970), Ree Morten (Of Previous Dissipations 1974), Rosemary Mayer (Spell 1977), Heidi Bucher (Borg 1976), Liz Larner (Cultures 1988, and Every Artist Gave a Breath 1988), Linda Besemer (Fold #7: Optical Objectile 1998), Margie Livingston (Folded Painting, small 2009), and Helen Calder (Orange Skin (125 fl.oz.) 2009).

9. Art New Zealand, Winter 2012, Number 142. P.34. Art Magazine Press.

10. From conversation with Hellyar, 2021.

11. Neimanis, Astrida. Bodies of water: Posthuman feminist phenomenology. Bloomsbury Academic, 2017.

CAMPING PAINTINGS (2015-ongoing). In 2015 I was teaching in Ohio and working to develop a hydrophilic (water loving) cellulose-based paint medium. During this time I began the CAMPING PAINTINGS series as a mobile residency project. I sewed lightweight canvases that could be adapted to a range of tent structures in different situations. The paintings have continued to accumulate over time, at multiple sites. Contemporary site-specific and site-responsive practices are influenced by the Situationist International, in extension of Surrealist politics. See Doherty (2009) and Wark (2011) for further discussion.

Untitled (2012), delaminated petrochemical latex paint works in the VCUArts studios, Richmond, VA. The petrochemical latex is heavy and I worked to ‘defy gravity’, grafting and peeling it into and onto existing and additional architectural fixtures. For the central piece, I added extra metal conduit before painting ten layers of latex onto the wall around the pipes, the paint was then peeled ‘onto’ the conduit, appearing as though it was threaded. At this time, I was beginning to think about alternative bio-based polymers that were lighter and also had the capacity for rehydration and different kinds of plasticity. I was using cellulose as a resist layer within the delaminations but didn’t yet understand how to make it a more resilient paint film.

Dayfolder (2013), VCUArts MFA thesis exhibition at the Anderson Gallery. The initial installation of this work occurred within a 24hr period and continued throughout the exhibition with layers of petrochemical latex paint peeled and ‘unfolded’ from surfaces over the course of several days. The transformations were photographed over time to expose the painting in stages, I often present these images out of sequence, destabilising the temporality and time signature of the painting as a singular image, the painting exists as a series of transitional or transitive images. For discussion of transitive painting see: Joselit, David. 2009. “Painting Beside itself.” October 130 (130): 125-134.

Medium reconfigured (2017), cellulose medium grafted onto studio surfaces. In 2016 I took the CAMPING PAINTINGS and cellulose medium projects to the Jan van Eyck Academy in Maastricht. The proposed project was to work on CAMPING PAINTINGS but I ended up focusing on the work with cellulose, developing its capacity for self-adhesion, reconstitution and/or rehydration.

Material costs: a conversation between Isabella Loudon, Melissa Macleod and Orissa Keane

Orissa Keane: I’ve been thinking about guilt and its function in relation to material use and processes. I know that for me there’s a constant weighing up of the varied costs of production, and a blind faith that what I do matters in some way and that its environmental impact is small and justifiable. I’ve noticed that guilt is a feeling that attaches to my lack of knowledge or belief in a clear solution. As artists who work primarily with objects and installation, I know you’re both very aware of your works’ environmental impacts, through your choice of materials and the production of waste.

Melissa Macleod: Yeah, I think sculpture gets disproportionately hammered with critique because materials are at the fore—they’re really visible. So both this self-criticism and to some extent external criticism falls on us unduly, really.

Isabella Loudon: I’ve been working with concrete for almost ten years now and I think a lot has changed in that time, specifically, our awareness of climate change and resources. How I feel now is very different to how I felt ten years ago. When I use concrete, I'm very aware of my health, but also that it creates waste. There will be leftovers, you can't use every little bit and not everything works out.

OK: That's an interesting point: what happens to the freedom to experiment when you're worried about what happens when things go wrong? It's not even waste, in terms of a wasted experiment—it’s a crucial part of making and trying things out. But the word ‘waste’ is so loaded, it strips it of the value it has within the rest of the process.

IL: Right, and in my work, gravity and chance play a big part, so I can't necessarily just make it once. Sometimes the first time will be to test the idea, and then I make another version, and it's the last one that works. But the five before don't.

MM: And they go in the bin.

IL: Yeah and even when I try to reuse and repurpose things, I can't save everything. I don't think I could make the kind of work I'm making without working in that way. I wouldn’t make anything at all.

MM: It's interesting, that process of making mistakes and what you do with that. And whether it can somehow be reincorporated, or if it's just chucked out. Guilt is an interesting word, and I keep seeing the word responsible too. I've started to hate those two words the more I read, actually, around art’s place within the climate crisis.

IL: I'm finding it a real battle to use concrete at all now. I've been using plaster, which is not any better environmentally, really, but it's not as bad for your health. When I had my basement studio in Wellington, I would be in there for hours and there was no ventilation—I was just wearing a mask. Even then, when you're in there and you take it off, it's all still in the air. I'll feel it afterwards, if I've done concrete work. And then I wonder about those people who do it for a job, all the time.

When you use plaster and concrete, you get all these little shards and waste so I've been filling up a bucket of these bits and trying to put them into new works. Some have worked when it’s used as bulk fill but mostly I do it because I feel guilty for throwing it out.

MM: The guilt, it's attached to daily life and the need to be conscious and recycle everything. In the case of the plastic dunnage bags in my work on an east wind, 2020, how they were perceived shifted over the making time. Single use plastic shopping bags were banned in 2019 and plastic was such a news item. Part of me didn’t want to go ahead with the work.

OK: Was that because of how you thought the work would be received?

MM: Essentially. I was bracing myself for criticism, but interestingly it never came. In my mind, I'd found a product that I thought was fascinating, because dunnage bags are designed to pack shipping containers, and to be filled with air from different countries, which felt totally fitting conceptually. Their function made sense to my work as I was similarly filling them with sea air. And actually, that sort of contrast between plastic and air was interesting.

So ultimately it was a good material to work with. Equally, my material decisions extend to the freighting and afterlife of the work, the life cycle. For the air work, I’d planned for it to exist as multiple iterations. That work is large scale once it's installed, but in its uninstalled state, can fit into a small compact area on the back of a ute. I think those considerations have increasingly come into play, an awareness of the mass of a work. The residue as well—where do you put it, if you're even keeping it? And beyond that, what else could it be? Who could I give it to as a material? What industry might use it? Could it be sewn into something else? Or become linings for something? More and more this thinking becomes part of how I work when I'm starting from base up.

IL: There's this image that NFTs and digital media are actually not taking up as much resources and space, but that's not necessarily true. In some instances the printed version can be the better option for the environment rather than storing billions of emails, PDFs, images, videos etc on the internet, which require more and more servers and more warehouses which use more energy. But because we don’t see that, it’s hard to recognise it as a problem.

OK: Same as the rubbish at the dump, right? We can call to mind an image of a pile of rubbish, but it’s hard to comprehend or imagine the scale at which it actually exists in relation to us.

Isabella Loudon, twisted, Robert Heald Gallery, Te Whanganui-a-Tara, 2021. Rubber tubes and screws.

Melissa Macleod, on an east wind, 2020. Sea air (New Brighton), dunnage bags, aluminium.

MM: I think as artists, we don't want to own all this. I think that's why the Frieze article by Tom Jeffreys, Challenging the Art World’s Material Waste (2021) was interesting. The article places the onus back on art institutions; environmental accountability needs to be embraced by the whole art mechanism, including gallery processes, and buyers. It can’t be all on artists. Just as one small example, sometimes the perceived pressure to use materials we don't want to, for environmental reasons, is partially due to limited funding.

IL: I think it depends on how you want the work to be read as well. If we start to look at art always through an environmentally concerned lens, then all other ideas are dulled. I love using concrete, its grittiness, its transition from liquid to solid, and the way you can cover things and it envelops them. Now, though, whenever I use it I am always concerned that work is going to be criticised first and foremost for being materially harmful for the environment. I’m not sure if this is true, but it definitely weighs on me.

OK: I wonder how it’s possible to have it both ways and say "fuck it, I really like the material and I want to play and explore it”. But to also make it work within an ethical framework which considers the environment? Or if they will always be opposing priorities?

MM: I’ve noticed artists who are consciously choosing natural materials, where in some instances those materials can be so loaded that the initial concept is drowned out by the material choice. In itself, the fact that an artwork can biodegrade is really interesting, but in these cases, actually it wasn’t meant to be the dominant aspect of the work.

IL: I think I'm definitely getting quite confused at the moment, I try really hard to reuse, repurpose, buy secondhand clothes, buy things that will last. But in my practice, I'm not interested in those things becoming the focus of the work. I’ve been working a bit with used rubber inner tubes. What drew me to the material is that it evoked something—these found materials have a past and this is reflected in their surface and form. The tube also has a relationship to the body, which I like, in its softness and in the forms it makes, and how it moves. Someone encountering my rubber tube works the other day asked me straight up “So is it about recycling?” No, to me it’s not. But by repurposing something that would otherwise go to waste, I do feel less guilty about making so many things in my trial-and-error style. But it doesn’t erase the fact that even as art it still exists as unnecessary stuff and ultimately as waste.

OK: And then we come back to that point where we have to remember that it is somehow necessary, otherwise a lot of people would be talking themselves out of making anything at all—some have already made that choice.

IL: I have to remind myself that art still has a place, and an important role in why we exist. It’d be pretty boring if there was none. I feel particularly driven to make things out of materials, not necessarily with ‘art’ as the outcome, but to engage in processes that are tactile and physical. Material stuff plays an important role in how we share thoughts, emotions and ideas with other people.

MM: I think your environmental footprint is just another layer to a complex maze you have already entered. The commitment to practice means you have already decided to take on all hurdles and stubbornly make, and push back. We are clever people—we can find ways to operate within this crisis if we really want to, if we value what we are saying. Art is about offering another angle. I live in a community that is often unheard; seeing inaction, and rising tides increasingly inundate the neighbourhood. Art practice for me is about finding a voice. But I am interested in injecting these politics as a layer within work so they can quietly filter through, so they’re not shouting.

We were talking about what people are criticising material-wise, and I was thinking about how it's easy to target certain materials, like plastic and concrete. But there are sneaky little ones, as well, sand, for example—it’s in concrete, and then there is its role in glass production. The mining of it globally is fraught with numerous ethical issues, on a human and environmental level. It is a finite and abused resource, worth billions. Here in New Zealand, Pakiri is just one example of a mined area where practices are unsustainable and impacting the coastal area—and historically this is a largely unmonitored process. We seem to see sand as an unending natural material for some reason.

It’s important to me to be informed about everything I'm using, and I don't know whether that need has maybe increased over time, this need to feel completely like you know the material inside out. I was really keen to learn where Fulton Hogan got the sand from that I used in Salt of the Earth (Linwood) (2017), but I probably wouldn't have been so interested in that ten years ago. I think a big part of feeling better about using materials is understanding their supply chain, so you can see it. It's also about being able to speak with integrity to your material decisions, being able to stand up for what you've done. Then you can start to direct sculptural remnants to other industries as well, or bring these industries on board. It doesn't always happen, but it's a nice feeling when it all aligns. Again it's sort of that cycle. For example, the sand I used was passed on to a local housing company. It became the groundwork for a building development across the paddock.

IL: I prefer not to know where things come from or to know too much about them. I feel it affects my initial impressions of a material and freedom to explore what it can do. By finding materials, rather than buying them, they come loaded with their own history, it’s just not one I can know. But there is something liberating in redirecting or repurposing a material that would otherwise go to waste. Also making art is expensive, the more that’s free the better! When I went to Whanganui I went to a bike shop and asked, have you got any bike tubes? They gave me a barrel.

But you know, those people were also holding onto them. More people are holding onto things I think, because they don't want to throw them out. So I definitely feel like I'm doing something good with those. I'm using them in an artwork but what happens after that?

Melissa Macleod, Salt of the Earth (Linwood), 2017. Sand.

Isabella Loudon, studio, October, 2023.

MM: It's interesting too to consider that artists aren't always making good work. Not all environmental artwork is successful, and what they're talking about might be being done better by a community project or by a scientifically led group. Sometimes artists are not very good at editing what we think is worthy and appropriate subject matter. Sometimes art's not the best vehicle or medium.

OK: There are times when it would be just as good or better to be just pointing at a thing, like to use your voice or platform to just point at these things that already exist, to the people who have already done the work. It can seem a bit parasitic when artists take from these initiatives if it’s not done in a particular and sensitive way.

MM: That’s when it hasn't had a shift has it? Artists have taken something real and researched, and haven’t reimagined it. I think the shift in that process is where this topic can become interesting, when something quite banal is manipulated and can be seen from a different angle. We have to be really aware of not just taking, which can easily occur, and thinking that putting an idea in a gallery is all it needs. That is something I'm really aware of because I'm often dealing with scientific research. It's really crucial that you're sensitive around that. Because you are just dipping a toe, compared to someone who's been studying a specialty area for 50 years. You're taking some often really detailed, fascinating material, that is totally someone’s world and sort of using what you need from it.

OK: And it’s easy to think that it’s justified because the artist is representing that information to a public that might not otherwise be exposed to it but that’s not always enough. I'm guilty of being drawn to a specific and poetic idea from science and wondering what I can do with it. It’s a trope of art making, once you start recognising it. It's when that next step hasn't been taken or hasn't been executed in full that we’re talking about being potentially harmful in its purposelessness. I know that science fiction, and speculative fiction is becoming quite a good vehicle for imagining the future in terms of climate adjustment, and artists are looking to fiction increasingly. It does take from science and present it for its own ends but it does so in a generative way.

MM: It's a really integral relationship at the moment, for artists that want to be a voice for climate crisis. It's pertinent, I think, in being able to learn from other research worlds and speak from a place of knowledge, because you can't come up with everything, you know, why would you come up with everything yourself? There are other industries and researchers out there that are interested in that collaboration.

Currently I’m looking at taking sea samples from areas that have flooded houses. There's lots of scientific information from the likes of the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA), and studies that have been done around these impacted communities. It’s really delicate because I’m also dealing with people's lived experiences of having had their houses and lives devastated. I’m conscious of the need to stand back and remember where my practice sits within this very real and lived space. There's a balance to find when you're essentially 'using' experiences of environmental crises, and wanting to make an art show from it.

In researching this topic, we looked to these sources and more for reference.

We mention ‘the Frieze article’, which is called Challenging the Art World’s Material Waste (2021) by Tom Jeffreys. https://www.frieze.com/article/challenging-art-worlds-material-waste

The essay discusses Helen Mirra’s 2019 manifesto CATHARTES 19, setting out a series of principles and practices responding to concerns for climate collapse, plastic waste and the treatment of nonhuman living beings. https://www.hmirra.net/information/pdfs/CATHARTES19_circular.pdf

Here is some basic information about sand mining from Friends of Pakiri Beach, an organisation aiming to stop sand mining at Pakiri. The legal battle is ongoing against the McCallum Brothers. https://friendsofpakiribeach.org.nz/sand-mining/

(audio description coming soon)

documentation from Proposition For Future Pet, 2020

Claudia Dunes

Claudia Dunes, Proposition for Future Pet, 2020. Detail. Photo: Rainer Weston.

Claudia Dunes, Proposition for Future Pet, 2020. Darkling beetle and larvae inhabiting and digesting polystyrene, 3D prints, plywood, shrinkwrap. Photo: Rainer Weston.

Mealworm tracks. Photo: Claudia Dunes

Meeting the Lake

Hana Pera Aoake

The first time I read Non-human Others and Kaupapa Māori Research by Te Kawehau Hoskins and Alison Jones it was a green light moment. I remember furiously sticking Post-it notes on so many of its passages. It articulated so much of the dissonance I had felt reading Rosi Braidotti, Bruno Latour and even Donna J. Haraway. It wasn’t necessarily that I disagreed with these philosophers nor did I struggle to understand their sometimes frustratingly overcooked understanding of being ‘in relation’ or of the interconnections that exist between other forms of life and matter that are around us. It was that it felt familiar yet I could not quite express why and the more I read the more I felt that language used by many of the post-human and ecological philosophies was inadequate at describing these complexities.

I have returned to this text a number of times and have even studied the endnotes and footnotes which have introduced me to new thinkers and has continued to feed my intellectual curiosity for years. It has deeply informed so much of the trajectory of my work, as an artist and a writer. It’s rich and generous and it feels important to acknowledge how indebted I am to the authors.

Whenever I re-read this text I find myself particularly drawn to excerpts describing the Māori exchange of hau, and the difficulty and impossibility of adequate translation of Te reo Māori kupu into English. For instance words in Te reo Māori are not merely words but an entire conception of how we (Māori) understand the world. A word like ‘whakapapa’ cannot be understood as just ‘geneology’ when it encompasses all life that exists, has ever existed and will ever exist, and cannot be bound to western ontologies of linear time. Translation is so important because we know from our history that certain words are not translated with care, such as when the missionary Henry Williams translated Te Tiriti o Waitangi into english overnight. We now know that there is a huge difference in meaning between kāwanatanga and tino rangatiratanga.

In this text Hoskins and Jones interrogate both the Māori ontological understanding of mauri, mana and wairua and the agency of the non-human, alongside that of a land deed signed by the Ngā Puhi rangatira, Hongi Hika. As a child I spent a lot of time on Hika's whenua visiting my grandparents who often took us for ice cream by the stone store. There is a ridge above the stone store that was Kororipo pā. Now a historic walking path, I once ran it with my younger cousins to help them train for their school cross country.

In 1814, Hika travelled to Sydney with his nephew Ruatara and Thomas Kendall, a missionary and arms dealer who had befriended Hika. Once in Sydney, they met the missionary Samuel Marsden, and invited him to move to their territory and establish the first Anglican mission in New Zealand. Hika, who belonged to the hapū Ngāti Rēhia, signed a land deed for 13,000 acres that later became Kerikeri by signing his mataora in 1819. By signing his mataora, he was not just signing his face, but ‘the living face or the face of well being’ marked on his body to connect him with his ancestors both those who had passed and those yet to come. By making these marks on paper, a dead tree (ancestor) remade into paper, Hika inscribed the essence of his lifeforce, the ihi, wehi, and wana of his being. Why on earth would he sign away this land from his people and thereby permanently alienate them from that land? No Māori rangatira would do this. It’s completely untenable. Therefore this cannot be regarded as a land deed in the European sense of the word, but rather as an exchange of breath, a hau, a promise, a living testament to the complexities within the relationships forged between Māori and Pākehā in the 19th century.

What of course complicates this narrative of bicultural harmony is what came next, which was not just the signing of both He Whakaputanga (1835) and Te Tiriti o Waitangi (1840), but the musket wars led predominantly by figures like Hika. When visiting Australia in 1814, Hika had studied European farming and had also started to grow much easier crops such as the potato and could therefore provide greater sustenance to his people. Hika had also made careful notes of European military techniques and purchased a number of muskets. It was the accumulation of these muskets that resulted in Hika being able to carry out a number of attacks on other iwi all around the country, including kidnapping some of my Ngāti Mahuta ancestors and massacring some of my Te Arawa whanaunga near Lake Rotoiti using Te Ara-o-Hinehopu track, commonly referred to as ‘Hongi’s track’. While re-reading this text, I cannot help but think also about the actions of Hika, whose exchanges made with Pākehā introduced technologies that vastly impacted upon so many other Māori communities. For better or worse these actions changed the course of history across this land.

As researchers and collaborators Hoskins and Jones have a methodology for writing together that can be described as embodying the Māori-Pākehā hyphen, which acts as a way of learning, understanding and exchanging hau.[1] It presents the best possible way forward for Māori and Pākehā, a way of meeting in the middle—waenganui. Both authors admit it's messy where they write as an endnote, “This is a complicated assertion. Our individual identities are far more fluid than this simple dualism (settler-Indigenous) suggests. Te Kawehau is a scholar in the western academy, for instance; Alison as a Pākehā defines her cultural identity in relation to/with Māori.”[2]

When you exchange hongi you infuse your life force with another, in a deeper sense it’s an acknowledgement of the ways in which human beings are entangled with forces and beings that exist within the world that cannot be neatly categorised into a cartesian split or be seen simply as hyphen.

When Māori introduce themselves to one another we describe ourselves as being a river, mountain, an entire tribe or ancestor.[3] ‘Ko au te awa, ko te awa ko au’, I am the river and the river is me.[4] When I speak to the rivers I belong to, I describe them as being a part of me in the literal sense. It is this way of understanding the world which has offered a creative approach to the interpretation of New Zealand law, which resulted in New Zealand passing a law granting legal personhood status to the Whanganui river in 2017. This law decrees that the river is a wholly living entity, from the mountain to the sea. It incorporates both physical and metaphysical elements of the river. This particular legal approach has set an international precedent that has been followed by some other countries including Bangladesh, which in 2019 granted all its rivers the same rights as people. This is perhaps an example of the ways in which Māori, and Indigenous people around the world, especially in the so-called global south, understand the rights and responsibilities they have to the non-human entities that exist around us. In the footnotes, an example Hoskins and Jones cite is that of the late Ahnishinahbaeotjibway thinker Wub-e-ke-niew where he wrote in his treatise We Have the Right to Exist: A Translation of Aboriginal Indigenous Thought: the First Book Ever Published from an Ahnishinahbaeotjibway Perspective that a person ‘meets the Lake’ rather than ‘goes to get water’.[5]

These beings and ideas of how to live with the non-human whether it is a building, a taonga pounamu, a tree, a river or lichen cannot be understood as having simply ‘thingness’, it’s much bigger than that, nor can it ever be something that can be owned in capitalist understanding of exchange. Sharing hau cannot equal the alienation of land forever in the form of a land deed, even if the stone store is built on top of it. We can only live in kinship with these forces and understand that they need to be cared for and respected as a part of the whakapapa of all beings that exist, have existed, and will continue to exist long after we leave this world.

1 Alison Jones, Kuini Jenkins. “Rethinking collaboration: Working the indigene-colonizer hyphen.”, Handbook of Critical Indigenous Methodologies. Denzin N, Lincoln Y, Smith LT. (eds). (New York:Sage Publications, 2008), pg. 471.

2 Te Kawehau Hoskins and Alison Jones, “Non-human Others and Kaupapa Māori Research”, (eds.) Te Kawehau Hoskins and Alison Jones, Critical Conversations in Kaupapa Māori. Huia Publishing: Wellington, 2017, pg. 61

3 Te Kawehau Hoskins and Alison Jones, “Non-human Others and Kaupapa Māori Research”, pg. 52

4 Ibid, pg. 52

5 Ibid, quoting (Wub-e-ke-niew, 1995, pp. 225, 218), pg. 61.

an extract from Non-Human Others and Kaupapa Māori Research[1]

Te Kawehau Hoskins and Alison Jones

Māori constantly evoke relational ontologies and recognise that the non-human world has agency. That is, Māori take for granted that the material things of the world – whether a forest, a lake, or a building – can ‘speak’ to human beings; we are always already in relation with certain material objects. And yet, Kaupapa Māori researchers and methodologies are relatively silent on the place of the material world and human–non-human relations in the framing of research. This chapter attempts to open this space through a Kaupapa Māori ontological and methodological engagement with post-humanist theory (also known as new materialism), which seeks to ‘consult non-humans more closely’. In this case, we consult Hongi Hika’s moko on the 1819 Kerikeri land deed, not as an artefact, but as a speaking subject. And rather than offering another interpretation of the moko-as-signature, we instead listen for what it might have to say.

Hongi Hika’s moko drawn by him. Church Missionary Society, London : Papers, MS-0700/A, Hocken Collections Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago

This ink-on-paper mark played a significant role in the earliest Māori–Pākehā relationships in Aotearoa New Zealand. Hongi Hika of Ngāpuhi drew his moko on 4 November 1819 on the second New Zealand land deed: 13,000 acres at Kerikeri in the Bay of Islands, sold to the Church Missionary Society for forty-eight axes. This mark, seen as a signature, is sometimes understood today as evidence of Hongi Hika having sold land to Pākehā (European) purchasers. As a result of this sale, the land, on which the town of Kerikeri now stands, shifted permanently into Pākehā ownership.

Many commentators have pointed out that the meaning of such land deeds from early nineteenth-century New Zealand becomes very unclear when two languages and cultures are engaged in a transaction such as sale of land. Did Hongi Hika sell the land, permanently alienating it from himself and his people for a few tools? Such an act was impossible. Commentators have pointed to the language used in the early nineteenth century related to land transactions, in particular tuku and hoko. Tuku – what Mauss (1990, 1925) called a gift exchange – cannot be translated easily into English; it refers to a form of exchange enacted with ceremony under the authority of a rangatira and which, at heart, is about forming and solidifying a relationship. Hoko is a simpler idea of exchange through trade. Discussion about the Treaty of Waitangi and the permissions it is seen to have granted alert us to these ideas. To quote Amiria Henare (2005, p. 121):

In Māori understandings, the Treaty took the form of a chiefly gift exchange, ensuring the retention of Māori authority alongside British governorship, and alliance between tribal leaders and the Queen of England ... In this document, two key terms were used to express the nature of the exchanges being agreed between the chiefs and Queen Victoria. The first was tuku, a term signifying the release of something important into the keeping of another, with the expectation of an ongoing relationship ... The second important term in the Treaty is hoko, a more prosaic mode of exchange, whereby transfers are effected without necessarily engendering a long-term relationship or obligation.

As Henare put it: ‘As part of the [Treaty] agreement, chiefs finally tuku-ed to the Queen te hokonga o era wahi wenua, the right to control the hoko-ing [selling] of land in New Zealand’ (2005, p. 121). Henare is suggesting that, although hoko might be understood more like ‘sale’ in European terms, it was a form of exchange existing under the aegis of tuku, which is always and already relational, unlike a sale, which is an act of alienation.

In western critical social research, it is possible, even necessary, to argue that Hongi Hika’s pen-and-ink moko on the land deed has many possible meanings: for instance, as his agreement that the Kerikeri land is sold and therefore alienated for ever (the ‘European’ view); as the act of a naïve native leader going along with a peculiar European ritual of sale that he did not fully understand; as an artefact in the history of European land alienation and robbery; the act of a shrewd Māori strategist recruiting ‘his’ Pākehā into his territory, binding them into a permanent alliance with his iwi.

What can be said about this ‘web of conflicting definitions’ (Stengers, 2008, p. 38)? A Kaupapa Māori sensibility dismisses the first meaning, given the idea of tuku above. The second meaning would also be untenable because it assumes that the great Hongi Hika was naïve, and this meaning only operates if we agree that the deed’s ‘true’ meaning is the first one. The third and fourth meanings, given they position Māori as having been colonised, or on the other hand, as taking charge of a complex situation, could be taken up by Māori as possible readings of the moko signature on the land deed.

In this chapter, we take a somewhat different approach again, still under the umbrella of what might be called Kaupapa Māori theory. Rather than debate legitimate interpretations of the moko, we attempt to focus on the physicality of the moko signature on the paper. It becomes a ‘thing’ that might, itself, have something to say. We encounter the drawn moko – our ‘object of study’ – as an organic, speaking subject (see Henare, 2007, for a related approach).

Māori ontology

Such an encounter makes sense in the Māori ontological world within which the mark on paper was made. This world takes it for granted that objects can speak, act, and have effects independently of human thought and will. Like all ontologies, this ontology was developed in a particular context of knowing that was itself moulded out of the problems of living, acting, and thinking in specific natural and social environments. Indigenous peoples, just as European peoples did before and outside the dominance of science (the Enlightenment) and the church, engaged with an environment that was already formed by powerful and weak forces and objects, where human beings had to negotiate with a capricious, live natural world.

Such everyday entanglement of nature and culture has produced lasting ontologies and epistemologies that identify humans in and with nature, and vice versa. This is easily observed today. Māori regularly engage in invocations that address and welcome, say, the plants or the sea when food or other resources are collected. Much of Māori everyday life is shaped by awareness of the human–non-human dynamic, as humans (as Māori[2]) constantly negotiate with the natural world, endeavouring to meet its dispositions and participate in its balances. It is widespread among Māori today to talk about a river, a mountain, an entire tribe, or an ancestor that lived hundreds of years ago as yourself: ‘Ko au te awa, ko te awa ko au’ (‘I am the river and the river is me’). This statement is not simply metaphor but a deep visceral identification as the animated embodied river, mountain, or ancestor (an observation well-known to western research, see for instance, Clammer, Poirier, & Schwimmer, 2004; Thomas, 1991). It remains common in Māori and other indigenous thinking for ‘objects’ – whether Hongi Hika’s tā moko on paper, a dead body, a forest, or a piece of greenstone – to be understood as determining events, as exerting forces, as volitional, or as instructing people.[3]

In post-Enlightenment western ontologies, objects such as tools and stones are typically experienced and known as inanimate matter, but for indigenous peoples ‘the liveliness of matter is grasped as quite ordinary’ (Horton & Berlo, 2013, p. 18). Within a Māori ontological frame, all beings and objects are experienced as having mana, a form of presence and authority, and a ‘vigour, impetus, and potentiality’ called mauri (Durie, 2001, p. x). Te mauri o te whenua, ‘the life force of the land’, or te mauri o te tā moko o Hongi Hika, ‘the life force of Hongi Hika’s moko’ on the paper deed, are perfectly mundane ideas to Māori. Terms such as mauri and mana name the interconnectivity of the human and non-human worlds.

So, within a Māori ontological context, the moko on the land deed lives; it is alive. It is not something old, inert, flat on a page, but something present, vibrant, and lively. It is a taonga, a sacred object holding Hongi Hika’s presence, his mana, his authority and chiefly power, co-present with the mana of his ancestors. His face and its embodied authority is before us, it encounters us; we are face to face with Hongi Hika. His presence carries an invitation to engage: to mihi – to speak greetings and make genealogical connections; to tangi – to remember and lament this dead relative and others; to hongi – to press noses and intermingle hau, breath, in a solemn enactment of a relationship, a joining of forces. These invitations by the moko assume and take seriously the idea that the object is animate and therefore in an active relationship with those who encounter it. In this sense, the object acts.

It speaks, it makes demands, and it draws a response from us.

Relationality

In calling forth a response, all beings and things have particular qualities and capabilities by virtue of their taking form in a relational context. The identity of ‘things’ in the world is not understood as discrete or independent, but emerges through and relates to everything else. It is the relation, or connection, not the thing itself, that is ontologically privileged in indigenous and Māori thought. Indeed, the general term for Māori people, tangata whenua, refers literally to land-earth-placenta-human: each forms the other. So, the vitality of things is possible not because of the intrinsic qualities of one object alone but because of ‘its relationship with the mauri [vigour, impetus, and potentiality] of others’ (Durie, 2001, p. x). This ontology – or, to use Salmond’s (2012) useful phrase, ontological style – produces a relationship between all things, including human beings.

Such a relational worldview is present in Māori research practice, which includes such elements as: karakia – to invite non-human forces to enable the research to proceed well, to enfold forces (bodies, spaces, ancestors, earth, and sky) into productive engagement; mihi – connections made to others and the earth-place from which they come; hongi – the pressing of noses in an exchange of breath that binds the parties together in a relationship of trust; kai – sharing of food that both seals a relationship between ‘researcher and participant’ as they work together in research conversations. And, because food is noa (non-sacred), it also counteracts the tapu or sacredness of the exchange of knowledge that is the basis of a research encounter. In other words, it is commonplace for Māori in the academy today to practice ontological understandings of the world in its ‘ongoing processes of becoming’ (Marsden, 2003). It is worth mentioning that these ontological practices are not only ‘cultural’ but also political acts; the phrase ‘Kaupapa Māori’ provides an umbrella term for the critical decolonising project that nurtures such theorising and researching with indigenous Māori ontologies and practices.

The matter of language

It is interesting to note that some similar ontological moves are occurring with-in western thought: ‘post humanist’ or ‘new materialist’ discussions in western social analysis have turned to re-examine the material world. Theorists have critiqued the idea of ‘the empirical’ as being understood as reality and radically separated from human apprehension of it. The argument that humans can only access reality through interpretation has become dominant in social sciences, including education with the rise of interpretivism, constructivism, and discourse theories. Post-humanist critics of this ‘linguistic turn’ in western social science point out that the dominance of discourse has left the object world alienated from us. Philosopher of science Karen Barad in Meeting the Universe Halfway (2007) and others such as Jane Bennett in Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (2010) foreground ‘the material’ – objects and things – which, they maintain, has been largely relegated to the shadows of modern social theory. But, argue post-humanist theorists, ‘ ... data have their ways of making themselves intelligible to us’ (Maclure, 2013, p. 660). ‘The material’ has agency and makes demands. It has, in Bennett’s (2010, p. 2) words, ‘thing-power’.4 (See also, Clough, 2009; Coole & Frost, 2010; Latour, 1993; Massumi, 2002.)

Some have pointed out that the position of objects ‘behind’ discourse is embedded in the very logic of European languages such as English. The usual logic of English grammar (object: passive; subject: active) reflects and reproduces a western subject–object dualism, and the ontological assumption that nature/object is a priori passive and culture/language is the source of active differentiation (Salmond, 2012; Viveiros de Castro, 2004). So, for instance, the simple descriptive statement that ‘... a shape is traced in ink. The shape represents the facial tattoo ...’ is ontological in that it places the act of drawing and the act of representation between the inked shape (nature or object) and its author (culture or human actor). The ink is being traced; the tattoo is being represented.

It becomes impossible, on this dualist logic, for the ink to have mauri (an energetic force), or for the tattoo to be the force of a person.

Method: How to proceed?

How might we encounter thing-power, or the mauri, of Hongi Hika’s moko mark? We must reach toward something that exceeds language: an attitude, a sympathy, a feeling, an openness.

The moko image is so many things: an object, a text, an image (reproduced on the pages of this book and also inhabiting an 1819 land deed), the mana (authority, presence) of a man and an iwi, a signature, a face, an object of exquisite aesthetic beauty; it is intensities of ink, intra-actions of shape and body, assemblages of paper, hau, and mana. The whole document is made of organic materials, paper and ink, with a wax seal. It provokes us in a multitude of ways.

How do we find our openness? How do we make ourselves available to thing-power, and vice versa? What research methods are suggested by Māori ontologies?

Can the debates in post-humanism help with this question? It is remarkably difficult to find suggestions for method in the new debates. This may be because ‘method’ is a human- centred activity where we are being asked to centre the object-that-would-have-been-called- data (Maclure, 2013, p. 558). An invitation to engage in intra-action seems as much about experience as method. Some new materialist theorists suggest that we proceed ‘by giving special attention to matter’ (Dolphijn & van der Tuin, 2012, p. 85) or that we ‘move beyond discursive construction and grapple with materiality’ (Alaimo & Hekman, 2008, p. 6). What we (Alison and Te Kawehau) find is that we, whether Western or indigenous scholars, are always caught in our human-centredness when we grapple with matter and then express that engagement in writing (in this case) in English. As the grapple-ees, matter remains, necessarily dualistically, the object of our attention. We feel stuck and uncertain about how to proceed.

Maybe this does not matter. Maybe the provocation is to encounter uncertainly the object world. This suggests method as an ongoing struggle and as constant attempts at connection rather than a set of rules for procedure. The resulting written accounts will have the (irritating or exhilarating) characteristics of fluidity, contingency, ambiguity – and obscurity. That is the territory we are working in; a Kaupapa Māori-inflected research method opens us to a range of new terms, impressions, languages, expressive forms, and ways of seeing.

Provocation

We would argue that such ideas might provide another provocation: Kaupapa Māori researchers could recognise in Bennett’s work (and others like her) something that makes sense within a Māori ontological approach to reality. She concludes her seminal book Vibrant Matter with a call to devise new ways of looking ‘that enable us to consult non-humans more closely’ (2010, p. 108); she suggests we researchers ‘encounter’ objects as they ‘command attention’ from us. That is, objects require, demand, engage, and exist in a relationship (with us and with other objects). But instead of being ‘merely’ a product of that relationship – to be understood as interpretation (for example, debris or taonga), objects simultaneously maintain their own singularity as ‘thing’, stoically outside our human encounter with them. Bennett seems to suggest that we turn to that thing outside and inquire of it, foregrounding the possibility that it might ‘have something to say’ to us in the process of our consultation.

How might the vitality of things such as Hongi Hika’s signature, or the mauri of his signature, which ‘exceeds comprehensive grasp’ (Bennett, 2010, p. 122), be engaged? Bennett is persistent. She suggests a ‘cultivated, patient, sensory attentiveness to non-human forces’ (p. xiv); an alertness to matter as ‘vibrant, vital, energetic, lively, quivering, vibratory, evanescent, and effluescent’ (p. 112), or, as Massumi (2002) suggests, a sensitivity to ‘the scent of a thingly power’ (p. xiii). These strange methodological suggestions remind us how radically difficult it is to write about matter’s vibrancy, at least when we write in English.

In te reo (the Māori language), we are not so limited. We have already mentioned terms such as mauri, hau, and mana that assume a liveliness of matter and a human–thing relationship. But it is not merely a matter of learning a few new words; in taking up these terms’ rich meanings, we are required to study their contextual meanings, their metaphorical fluidity, and their multi-layered ability to access the real. Such immersive study is an encounter with the intricacies in the object’s murmurings, not heard at first. It still might be a struggle to express those inchoate meanings in writing and in the logic of a research article, but isn’t this difficult work what Kaupapa Māori is all about?

Notes

1. A version of this paper was first published in 2016 as ‘A Mark on Paper: The Matter of Indigenous-settler History’ in Carol Taylor & Christina Hughes (Eds.) Posthuman Research Practices in Education (pp. 75–92). London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. This first version was written with a European audience in mind. This one is written for a more local audience.

2. We do not assume that all Māori think or act in these ways, or for that matter, that all Europeans think and act assuming a Cartesian dualism between nature and culture. We speak here about ontologies and languages rather than individuals. It is also the case that neither indigenous nor non-indigenous scholars operate ‘outside’ scientific forms of thought. Even as scholars might act against (or ‘betray’, as Stengers, 2008, p. 38 puts it) science and empiricism, we are forced to address it or write in terms intelligible to it.

3. Beyond Māori examples, one does not need to look far into other indigenous ontologies to see evidence of the world not as nature/object and culture/subject in interaction but as a form of related sociality. For instance, indigenous scholars such as North American Indian academic Vine Deloria (Deloria, Foehner, & Scinta, 1999, p. 37) remind us that, in Sioux metaphysics, all human and non-human beings are interrelated, and each form of being has its own character: sunflowers ‘engage in purposeful action’ by using buffalo as a transport mechanism for their seeds; stones’ character or personality is stillness. The Ojibwa people know that all things, as beings, express themselves in movement or personality: thunder can speak intelligibly; the natural world is full of signs that may or may not be interpreted by humans (Ingold, 2004). In the Ahnishinahbæópjibway language ‘there is no subject acting upon object’; objects exist in equal relation to others including humans: so a person ‘meets the Lake’ rather than ‘goes to get water’ (Wub-e-ke-niew, 1995, pp. 225, 218).

4. In English, theorists have needed new vocabularies to encounter a material world different from that assumed in dominant western epistemologies. So it is not uncommon to find such phrases as nature-culture, agential, matter-energy, the material-discursive, intra-action, assemblages, relata, thingly power, entanglements, and flows. For instance: ‘matter is substance in its intra-active becoming – not a thing, but a doing, a congealing of agency’ (Barad, 2008, p. 139); ‘An assemblage, in its multiplicity, necessarily acts on semiotic flows, material flows, and social flows simultaneously’ (Deleuze & Guattari 1987, p. 22); ‘... this particular mode of matter-energy resides in a world where the line between inert matter and vital energy, between animate and inanimate, is permeable’ (Bennett, 2004, p. 352). Bennett (2010, p. 119) confesses that in order to write her book Vibrant Matter, she needed to compose and recompose words and sentences as she tried to find appropriate verbs (intra-act) and nouns (actant, intra-action) for her argument.

References

Alaimo, S. & Hekman, S. J. (Eds.). (2008). Material Feminisms. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Barad, K. (2008). ‘Posthumanist Performativity: Toward an Understanding of How Matter Comes to Matter’. In S. Alaimo & S. J. Hekman (Eds.), Material Feminisms (pp. 120–156). Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Bennett, J. (2004). ‘The Force of Things: Steps Towards an Ecology of Matter’. Political Theory, 32, pp. 347–372. Bennett, J. (2010). Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham: Duke University Press.

Clammer, J., Poirier, S., & Schwimmer, E. (Eds.). (2004). Figured Worlds: Ontological Obstacles in Intercultural Relations. Toronto, ONT: University of Toronto Press.

Clough, P. T. (2009). ‘The New Empiricism: Affect and Sociological Method’. European Journal of Social Theory, 12(1), pp. 43–61.

Coole, D. H. & Frost, S. (2010). New Materialisms: Ontology, Agency, and Politics. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. Deleuze, G. & Guattari, F. (1987). A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. London, UK: Athlone Press.

Deloria, B., Foehner, K., & Scinta, S. (Eds.). (1999). Spirit and Reason: The Vine Deloria, Jr. Reader. Golden, CO: Fulcrum Publishing.

Dolphijn, R. & van der Tuin, I. (2012). New Materialism: Interviews & Cartographies. London, UK: Open Humanities Press.

Durie, M. (2001). Mauri Ora: The Dynamics of Māori Health. Auckland, NZ: Oxford University Press.

Ellis, N. (2014). ‘Ki Tō Ringa Ki Ngā Rākau ā Te Pākehā? Drawings and Signatures of Moko by Māori in the Early 19th Century’. Journal of the Polynesian Society, 123(1), pp. 29–66.

Henare, A. (2005). Museums, Anthropology and Imperial Exchange. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Henare, A. (2007). ‘Taonga Māori: Encompassing Rights and Property in New Zealand’. In A. Henare, M. Holbraad, & S. Wastell (Eds.), Thinking through Things: Theorising Artefacts Ethnographically (pp. 47–67). London, UK: Routledge.

Henare, M. (2007). ‘The Māori Leaders’ Assembly, Kororipo Pā, 1831’. In J. Binney (Ed.), Te Kerikeri 1770–1850 (pp. 112–118). Auckland, NZ: Auckland University Press.

Hohepa, P. (1999). ‘My Musket, My Missionary, My Mana’. In A. Calder, J. Lamb, & B. Orr (Eds.), Voyages and Beaches: Pacific Encounters (pp. 180–201). Honolulu, HW: University of Hawai‘i Press.

Horton, J. L. & Berlo, J. C. (2013). ‘Beyond the Mirror’. Third Text, 27(1), pp. 17–28.

Ingold, T. (2004). ‘A Circumpolar Night’s Dream’. In J. Clammer, S. Poirier, & E. Schwimmer (Eds.), Figured Worlds: Ontological Obstacles in Intercultural Relations (pp. 25–57). Toronto, ONT: University of Toronto Press.

Jones, A. & Hoskins, T. K. (2016). ‘A Mark on Paper: The Matter of Indigenous-settler History’. In C. Taylor & C. Hughes (Eds.), Posthuman Research Practices in Education (pp. 75–92). London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Jones, A. & Jenkins, K. (2011). He Kōrero: Words between Us – First Māori-Pākehā Conversations on Paper. Wellington, NZ: Huia.

Latour, B. (1993). We Have Never Been Modern. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Maclure, M. (2013). ‘Researching without Representation? Language and Materiality in Post-qualitative Methodology’. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 26(6), pp. 658–667.

Marsden, M. (2003). The Woven Universe: Selected Writings. Otaki, NZ: Estate of Rev. Māori Marsden.

Massumi, B. (2002). Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Mauss, M. (1990, 1925). The Gift: The Form and Reason for Exchange in Archaic Societies. (Trans. W. D. Halls). London, UK: Routledge.

Rihari, H. (2010). Brief of Evidence by Hugh Te Kiri Rihari, 3 June 2010. Te Paparahi o Te Raki Tribunal Inquiry, Waitangi Tribunal, WAI 1040, B013(a).

Salmond, A. (2012). ‘Ontological Quarrels: Indigeneity, Exclusion, and Citizenship in a Relational World’. Anthropological Theory, 12, pp. 115–141.

Shortland, W. (1990). ‘The Unseen World’. New Zealand Geographic, 5. Retrieved from http://www.nzgeographic.co.nz/

Stengers, I. (2008). ‘Experimenting with Refrains: Subjectivity and the Challenge of Escaping Modern Dualisms’. Subjectivity, 22, pp. 38–59.

Sundberg, J. (2014). ‘Decolonising Posthumanist Geographies’. Cultural Geographies, 21(1), pp. 33–47.