Emerita Baik, Maia McDonald, and Nââwié Tutugoro

Bedrock

15 Apr — 30 May 2021

Bedrock

Emerita Baik, Maia McDonald, and Nââwié Tutugoro

Exhibition preview: Wednesday 14 April, 5:30pm

Exhibition runs: 15 April – 30 May 2021

Exhibition talk with Emerita Baik, Maia McDonald, and Nââwié Tutugoro: Wednesday 14 April, 4:30pm

“I think about how objects are social, how they speak with us. How they placate us.” Nââwié Tutugoro wrote this earlier in the year, responding to an email thread about the exhibition Bedrock. Her words hold some of the ideas connecting works by Tutugoro, Emerita Baik, and Maia McDonald: the things we make to live with and come home to, the material languages that bring strength or ease in phases of transition, the things that help us remember who we are and where we stand. In Bedrock these foundational relationships are explored across three practices.

Emerita Baik’s I love more than two loves (2019) is a series of quilts made in response to the experience of living ‘between’ languages (specifically, Korean and English), cultures, and her mother's experiences since moving to Aotearoa from Korea before Emerita was born. She writes, “My work is pushed through creating new narratives for migrant bodies”, both known individuals and broader audiences. Each quilt is named for someone she knows who lives with a language barrier. The making process involves a traditional Korean (nubi) and Western quilting techniques, and ramie fabric as well as materials associated with everyday routines, including sleeping bags, shower curtains, and weedmat, alongside textiles painted by the artist. Hung in the gallery space, the quilts are both hefty—these forms may be rocks with molten centres, or rain-laden storm clouds animated by static electricity—and malleable, something you might fall into to be held, like falling onto a bed.

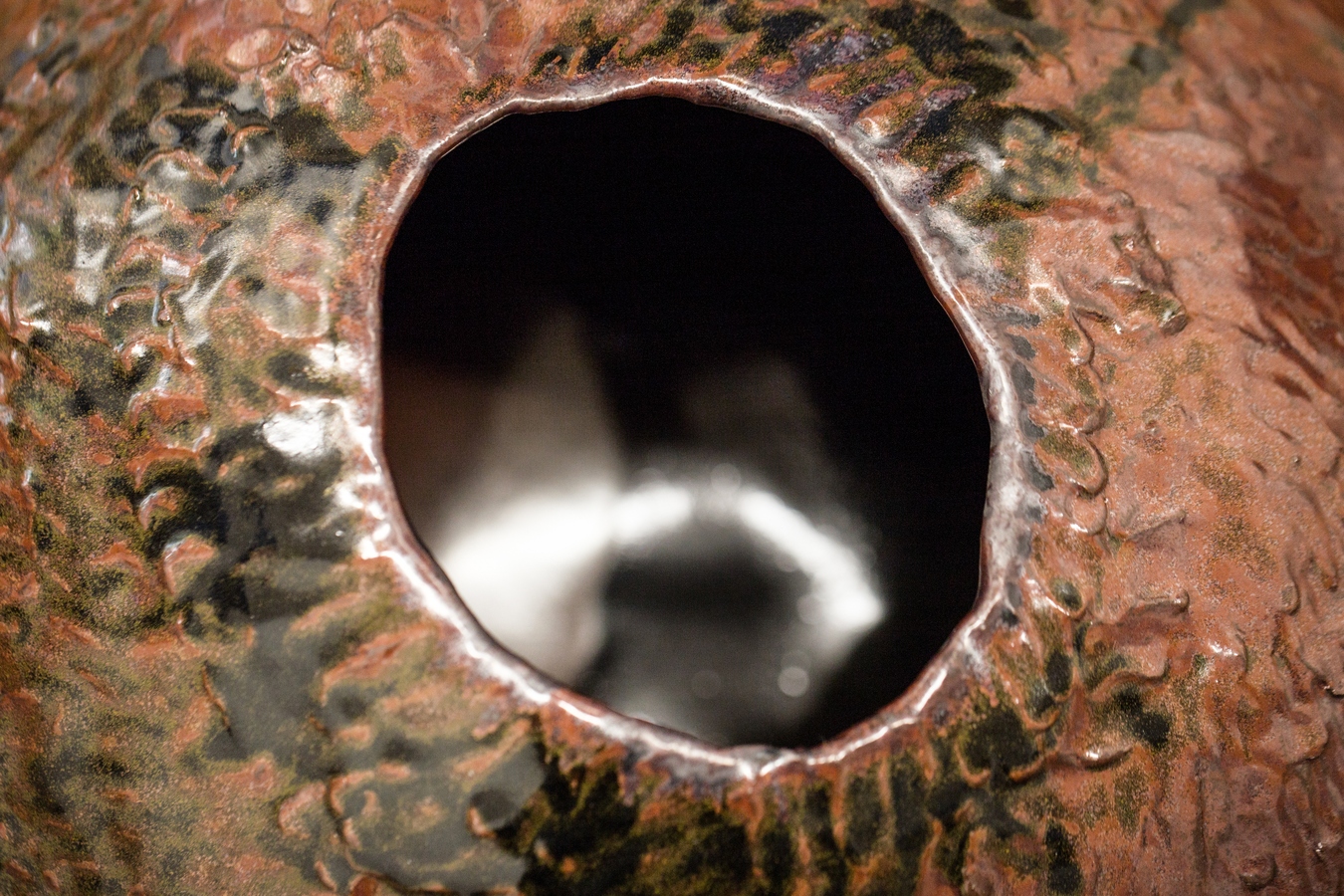

Maia McDonald’s Hāpai is a group of three large ceramics, made with uku (clay), glazed and fired in her studio in Ngāmotu New Plymouth. Hāpai means to ‘take up, to shoulder’. It can also mean ‘to begin’ in the sense of a waiata or karakia, ‘to set off’, or ‘to rise’ like the sun (Te Aka Māori Dictionary). Holding the transformative possibility of each of these verbs, the work itself has also moved through states of change: from earth and water, through fire, to ceramic. McDonald acknowledges this transition in terms of tapu and noa, and through tikanga responsive to the shift of states fundamental in ceramic practice. Ceramic objects hanging by the works may be used to strike the larger forms, the resonant sound they make just one recognition of the non-visual properties of the material. In the artist's words, “The small ceramic works were made to ignite the mauri (life force) within the larger ceramic works, something like the sparks resulting from a flint rock being struck. The sound brings a new texture into the space.”

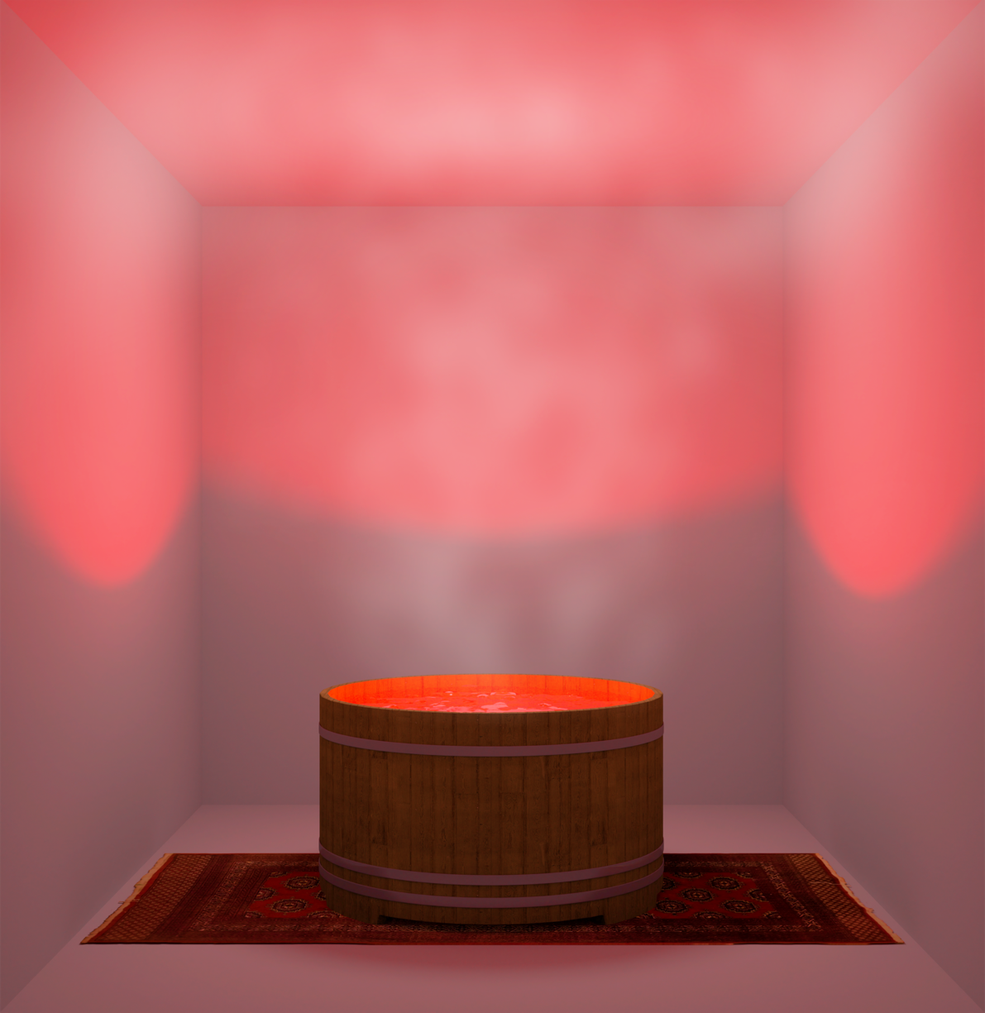

Nââwié Tutugoro’s installation, And a blue vocoder, and everything is blue for them (2021), centres around an animated hot pool image, which bubbles, steams, glows. Originally shown online as part of May Fair Art Fair in 2020, here the hot pool form is returned to as a projection, reconfigured in response to The Physics Room space and the artist’s ongoing research around migratory movements: departures, returns, navigating urban and institutional spaces as an indigenous woman. A number of bindles (cloth bundles of belongings attached to the end of a stick) occupy the gallery, alongside objects and materials collected by the artist in her daily commutes between te motu Waiheke and the city, her home and studio. There is a strong sense that these objects will not be here forever, that they mark the space perhaps as remnants on a tideline would: with precision, and temporarily, before returning to the sea.

In the context of a contemporary gallery—where newness is often emphasised, where projects come in and out with staccato frequency—continuity of relationships is a necessary bedrock. In Baik, McDonald, and Tutugoro’s practices, the makers’ relationships with specific and physical materials are not distinct from a wider relational network including whakapapa, friends, spoken and intuitive languages. These works bring into the room personal narratives about what we each leave the house with, carry with us, and what we return to. Finally, Bedrock is about standing and feeling your feet on the ground, the swamp or the concrete, where you stand.

--

Emerita Baik makes ‘sculptural paintings’, working across media. She holds her BFA (Hons) from Toi Rauwhārangi College of Creative Arts Massey University, Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington (2018). Recent exhibitions include The fairy and the woodcutter, Robert Heald Gallery, and 꿈 / ɯnʞʞ, Enjoy Public Art Gallery, both Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington (2020). Her work will also be included in The inner lives of islands, Te Tuhi, Tāmaki Makaurau (upcoming, 2021).

Maia Robin McDonald (Ngaati Mutunga, Urenui Marae; Te Ati Awa, Parihaka) works primarily with uku (clay). She is also a writer and curator, and until recently was working as Indigenous Curator at Koori Heritage Trust in Naarm Melbourne. McDonald completed her BFA in Photo Media (Hons) at Toi Rauwhārangi College of Creative Arts Massey University, Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington (2017), and a Diploma of Māori Art and Design, Te Wānanga o Aotearoa, under master uku artist Wi Taepa. This year she has solo exhibitions at Kaukau Gallery, Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington and SPAC_E Gallery, Te Ahuriri Napier, and is part of Mercury in Retrograde at Te Uru Waitākere Contemporary Gallery, Tāmaki Makaurau.

Nââwié Tutugoro works mainly in sculptural installation, and recently completed her master’s degree through Elam School of Fine Arts, Tāmaki Makaurau. Tutugoro’s father is Kanak (South Pacific) and mother is Anglo-Argentinian and European; she lives on te motu Waiheke. Recent exhibitions include cassette tape garden recorder, May Fair Art Fair (online) (2020), and Kanaky is my fate, MFA graduation exhibition, Elam School of Fine Arts, Tāmaki Makaurau (2021).