Emma Fitts and Rosalind Nashashibi

The air, like a stone

16 Jun — 30 Jul 2023

The air, like a stone

Emma Fitts and Rosalind Nashashibi

Curated by Abby Cunnane

Whakatau and opening: Friday 16 June, from 5:30pm

Exhibition runs: 16 June – 30 July 2023

This exhibition brings together a feature-length 16mm film by Rosalind Nashashibi, Denim Sky (2018-2022), and a newly commissioned installation by Emma Fitts, From heat to translucence / your mineral touch (2023). Very different in many ways, Nashashibi and Fitts’ works share a concern with non-nuclear relationships—human, material, social—and non-linear time. In these works signs and omens, weather, friendships and the materials themselves power the narrative and decision making, rather than chronological time and conventional relationships. As a whole, The air, like a stone is an invitation to think about what happens when something intuitively or collectively experienced becomes momentarily solid and substantial, like a stone, or a good story.

Denim Sky is made with friends and family as cast, in three parts and over three years, across locations including the Orkney Islands, the Scottish National Gallery, and the Baltic Sea. The film is based on a fiction that a group of people has come together to experiment with a form of space travel that uses non-linear time. This narrative, prompted by science fiction writer Ursula K. LeGuin’s The Shobies’ Story (1990), is told, embodied, retold, by the people in the film as they move into and out of the collective.

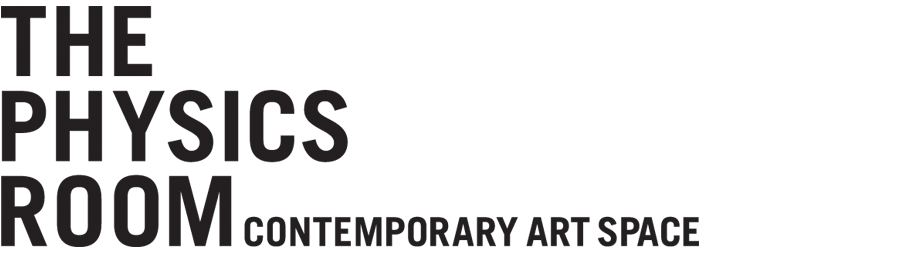

In Fitts’ work the core relationships are between materials, which are structurally inter-reliant elements in a larger system, and time. Made from weathered canvas, felted wool, aluminium and wooden rods, and fabric ties, the work occupies the front of the gallery space. It remains lit and visible all night for the duration of the show, expanding the regular hours of the gallery, and alluding to time measures which are astronomical, tidal, or responsive rather than programmed.

The blue, blue-green, and aged-peach canvas panels that form the body of Fitts’ installation are repurposed from an earlier work, which occupied an outdoors site in Tāmaki Makaurau for a year. Originally dyed with an intense saturation of Flashe pigment, the canvas is also marked by the weathers it has endured since. Over the time since it left the studio it has aged and faded, and its texture slightly stiffened by the absorption of salt, rain and other forms of airborne moisture, and carbon dioxide. In this sense it could be considered a very direct form of landscape painting, physically documenting the conditions of its former site.

Fitts’ wall-based work for The Physics Room is made in response to its Ōtautahi site, and to this time of year. The exhibition opens at a time of year when the days are short, nights long. The Matariki star constellation has set for now, in the thirteenth lunar month, and the new year is about to begin with its rising in July. On grey days the gallery walls appear bone-white, and even on bright days the low sun only enters this part of the gallery for a short period in the afternoon, when the walls are briefly animated by the shifting light. This part of the space is typically occupied by a seated gallery minder, and houses The Physics Room Library; both have moved for the duration of this project. It is as if the work has come in like a tide, reordering things with its momentum.

The work also registers a number of other time scales. Its arced seams, and other marks on the canvas are drawn from looking at galaxy structures, gravity-organised systems of stars and their remnants, gases, dust and other matter. The work’s form was also influenced by Fitts’ observations of the architecture of Mount John Observatory at Takapō, and the work of American abstract painter Dorothea Rockburne, which is grounded in mathematics and astronomy. The work’s title, From heat to translucence / your mineral touch, evokes states of transformation that occur in the natural world, in rocks or the ocean, but may also be associated with a human body and the chemical or emotional reactions that occur within it.

A number of horizontal rods support the planes of canvas, secured with a system of fabric tethers fed through steel eyelets, so that the canvases counterbalance each others’ weight. These straight lines heighten the sense of the work as a drawing, doing the work of structuring masses, in both a practical and compositional way. A long roll of felted wool, originally made by the artist in 2017, anchors the whole thing to the ground. As well as being a body of wool fibres, fused and sinewed, the felt records the intense, repetitive movements of the artist—arms, torso, whole body—in the making process. It is these repeated movements, over time thickening into a solid material, that gives felt its substance. Perhaps its role here is something like that of fascia, the sleeve of skeiny tissue that holds every bone, nerve, muscle and blood vessel in our bodies in place.

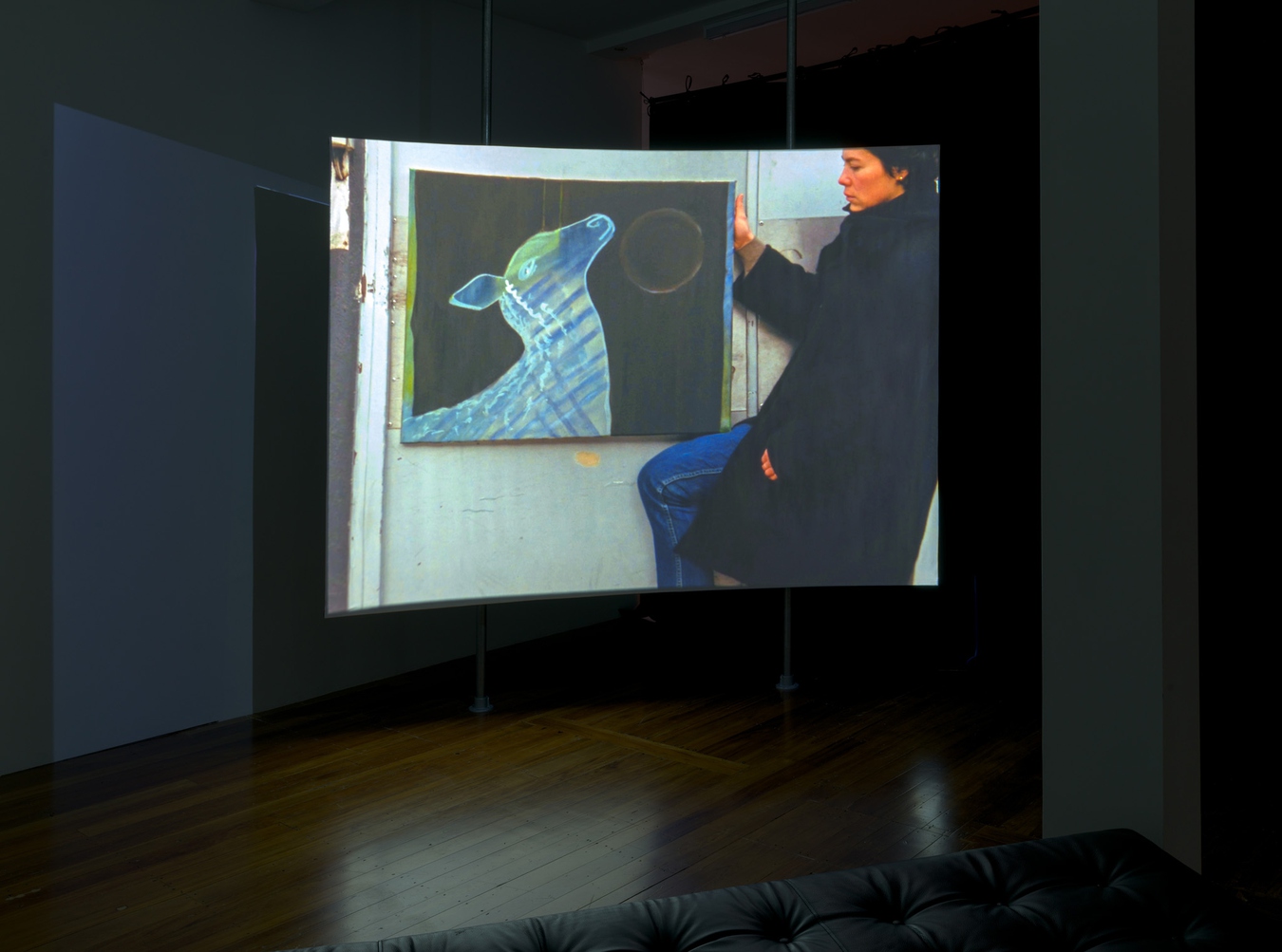

Moving into the body of the gallery, you enter Nashashibi’s film, which runs in three chapters: ‘Where there is a joyous mood, there a comrade will appear to share a glass of wine’; ‘The moon nearly at the full. The team horse goes astray’; and ‘The wind blows over the lake and stirs the surface of the water. Thus visible effects of the invisible show themselves’. These titles were determined by the artist’s use of the I Ching, an ancient divination text from around 1000 BC used for guidance and decision making. In this case it was activated by the flipping of three coins. Drawing on divination, the LeGuin fiction’s framework, and leaving the unfolding of the plot largely up to the unscripted and often routine activities of the group’s members, Nashashibi foregrounds alternative logics in place of chronological time, and standard directorial agency. It is the characters’ sharing of stories, internal to the film, that organises them, locates them in space and time as well as in relationship to each other.

Across Nashashibi’s film, which has been described as “a spell or a promise for a new and more freeing type of family structure” (LUX), the idea of moving outside of linear time is speculated on with optimism, as a space of potentiality. As one character says, perhaps it will mean you can travel in space without losing all your loved ones, or that processes of ageing are eluded. At other times it is reckoned as threatening to the biological body, which is not equipped for life in space, outside of time: “saliva, sperm and bile, they can [...] start boiling”.

The first chapter of the film sets the scene, bringing the intergenerational crew together to discuss the possibilities of travel outside of time as we know it, including their fears about what could happen to communication and memory, romantic and other forms of love. “Love is waiting to be loved” says one: what does it mean to move outside of the currents of anticipation and desire? In the second chapter, new members are present, and the group sit in a cinema receiving mission instructions. A central question arises—can stories survive in space?—and is discussed in the jacuzzi by older members of the crew. One of the crew leaves, destabilising the coherence of the whole.

In the third chapter of the film, the group are on an island in Orkney. Everyone is two years older than when the project began, and they speak about events that have happened in previous chapters. Even as the film’s atmosphere diffuses into a dreamlike state, the characters’ relationships have settled into more conventionally definable ones. The mother, Rosie, walks through an empty National Gallery in Scotland reflecting on what has happened, and on a new relationship in her life; later she attends a psychic reading with her son. A child is described as “essentially a lion”; the filmmaker recalls the chin exercises advocated by her grandmother to keep her neck long; a fish omen evokes puberty. In this final section of the work, metaphors, signs, and anecdotes offer ways of visualising time and relationships.

Beyond their attention to time, there are of course other links between these works. Not least of these is felt in the body, in the gallery, where the soundtrack from Nashashibi’s film (including original composition for the film by Tom Drew, Lithuanian piano music, a piece by 17th century composer Henry Purcell, Joan As Policewoman, field recordings and the voices of Nashashibi’s friends and family) fills the whole space. In what could be seen as a reciprocal way, it is Fitts’ work that you see as you enter the room, that marks the arrival and departure of visitors and also the time when the room itself is unoccupied. Finally, this non-hierarchical interrelation between the two works is what coalesces in the space, what becomes solid, “thick” (LeGuin’s term), able to be tested or shared—for the time being.

- Abby Cunnane

--

Emma Fitts’ practice spans painting, photography and sculpture. Recurrent themes in her works include queer art histories, Modernist textiles and architectures, and the idea of biography, with a particular emphasis on emotion and affect. Fitts studied at the University of Canterbury, Ōtautahi, and completed an MFA at Glasgow School of Art, Scotland. Recent solo exhibitions include Petal, Melanie Roger Gallery, Tāmaki Makaurau, 2023; Lapping at your door, Objectspace, Tāmaki Makaurau, 2022-23; In The Rough: Parts 1, 2 & 3, Te Uru Waitakere Contemporary Gallery, Titirangi, 2019; and From Pressure to Vibration: The Event of a Thread, The Dowse Art Museum, Te Awakairangi Lower Hutt, 2017. Recent group exhibitions include Tree in a Hurry, The National, Ōtautahi, 2022; Evolutions of Galaxies, MADA gallery, Monash University, Naarm Melbourne, 2022; and Touching Sight (with Conor Clarke and Oliver Perkins), Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna Waiwhetū, 2020-2021. Fitts returned to Ōtautahi from the UK in 2014 as the Olivia Spencer Bower recipient, was a McCahon House resident for winter 2018, and completed the Fulbright-Wallace residency at The Headlands Center for the Arts, San Francisco, in 2019. Fitts lives and works in Ōtautahi Christchurch.

Rosalind Nashashibi is a painter and filmmaker. Her work often deals with everyday observations alongside mythological elements, and considers relationships between community and extended family. She studied at Sheffield Hallam University and Glasgow School of Art, where she received an MFA in 2000. As part of her Master’s degree, Nashashibi participated in a three-month exchange program in Valencia, California (US) at CalArts. Nashashibi became the first artist in residence at the National Gallery in London (UK), after the program was re-established in 2020. Recent solo exhibitions include Hooks, Nottingham Contemporary Gallery, Nottingham, 2023; Monogram, at Radvika Palace for CAC Vilnius and Carré d’Art, Musée d'art Contemporain de Nîmes, 2023; An Overflow of Passion and Sentiment, National Gallery, London, 2021; and Future Sun (with Lucy Skaer), S.M.A.K., Ghent, 2020. Nashashibi was a Turner Prize nominee in 2017, and represented Scotland in the 52nd Venice Biennale in 2013. Her work has been included in Documenta 14, Manifesta 7, the Nordic Triennial, and Sharjah 10. Nashashibi lives and works in London.