Group Show

The Water Show

07 May — 31 May 2008

Whether you have to go out of your way to get the good stuff, or pay each time you turn on the tap, water continues to be a subtle but problematic entity within many urban contexts. The Water Show consequently addresses some of the issues faced when water is treated as a resource. Incorporating works by a range of New Zealand artists such as Sam Hartnett (Auckland), Amy Howden-Chapman (Wellington), Sophie Jerram (Wellington), Miranda Parkes (Christchurch) and Susie Pratt (currently based in Wales), The Water Show also presents responses to more local contexts via inclusions by Harold Grieves & Alan Lacan and Jonathan Smart.

Whether tracking the politics, infrastructure and spheres of influence that underlie the management of water, or documenting more subjective terrain with an eye for the ecological as well as the aesthetic, The Water Show ultimately seeks to raise awareness and offer its audience some creative responses to water’s circulation and its ever increasing value.

Sophie Jerram’s 2007 show at Wellington’s Enjoy gallery, Oil on Troubled Water is, in many ways, the spur for this show at The Physics Room. There, Jerram, contrasted a montage of Hollywood representations of oil-discovery wealth against a small fridge full of bottled “grey” water taken from a rather dubious source. The implication, was of course, that water discovery would be the new “boom” economy, a thread her current work has been investigating. For The Water Show, Jerram has been documenting Otago water prospectors as they drill private water bores for farmers who are keen to find a stable water supply. Describing these entrepreneurs as iconic ‘prospectors’ who are ‘prepared to get their hands dirty in the exploitation of natural resources’, Jerram also lets loose her doubling back to that Hollywood iconography, this time, James Dean playing Jett Rink in the film Giant where labour is sexualised as masculine prowess. As Jerram describes, ‘what I see in the images of these men is an apparent nonchalance as they rut through the earth in search of free flowing fluid. There is nothing suppliant or reverent in their stance. Neither do they seem to be revealing any great pleasure in their work but instead a cocky assumption that the ground will provide’.

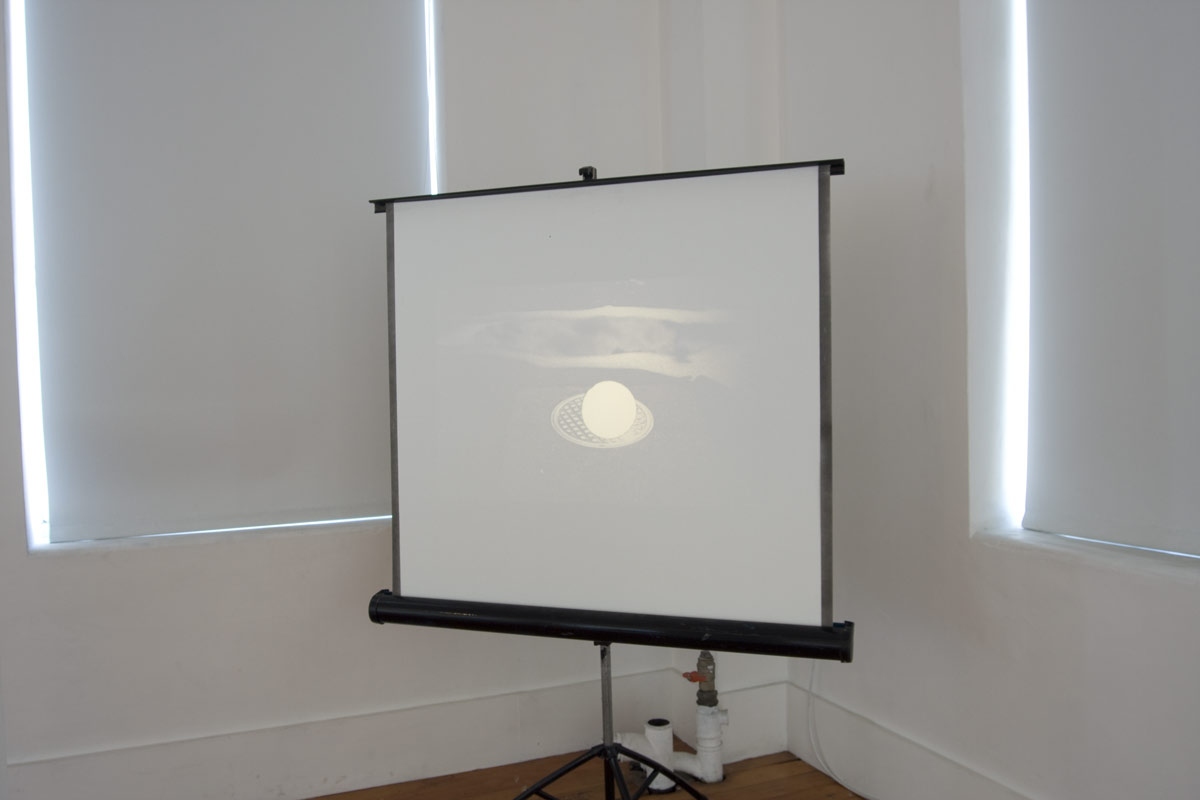

Amy Howden-Chapman has contributed three distinct works to The Water Show. The first, Invisible storm water drains is a slide projector work comprised of 80 hole-punched images of storm water drain covers. Creating a circle of white light in the middle of the projected image, the slides refer to the way that water, so integrated and integral to a city’s infrastructure and daily life is often invisible. Hidden underground, or concealed behind walls, water is always in-waiting, patiently abiding our needs. A second work, My boyfriend asleep in a waterfall, documents the social imaginary role a waterfall quilt plays out as part of a gift economy. Divided into three and shared out amongst generations, the quilt plays out a genealogy of descent, much like the billowing waterfall or the “natural” course of a river. It is a kind of trickledown that illustrates the metaphorical implications of water as a purifying and independent entity, a “natural course” which is bound to the mutually reassuring ideas of solace and commiseration. These “naturalised” implications are also referenced in Howden-Chapman’s third work, My Dad, John and the MONIAC.This is a short video work where her father explains the way the MONIAC (the, Monetary National Income Automatic Computer) uses “water flow” to act as an economic modelling device. The discussion centres around how the model fails to accommodate environment derogation and how it misleading uses water as a “naturalised” property with a “dependable” flow cycle.

Miranda Parkes’ two video works are a pretty good example of what she dubs her research. Better known as an abstract painter of “decadent canvases” which twist and contort the confines of the frame, she is also an astute cataloguer of anomalous formal moments taken from everyday occurrences. Whether they’re serendipitous lighting glares, anomalous reflections or simply her camera’s framing of everyday occurrences, she attempts to catalogue these sightings as informative events which add to the cadence of her painting practice. These two works also show a cultural inflection to her selection process, perhaps picking up on what can be called the post-industrial sublime, those moments when we recognise our culture’s disenfranchisement from nature and our often hyper-real attempts to make up for this shortfall. This is certainly the case of Waterfall which opaquely records a banal reproduction of a stereotypical waterfall, highlighting as it does the artifice and framing that these spectacular moments of nature-scenery require. Likewise, the reflecting waters of Lake Pukaki, which imbued in an almost cathartic, spiritual attribution, is an entirely mesmerizing lure, but which, on closer inspection, is in fact, merely a camera glitch.

Susie Pratt’s video work was made in response to the flooding of an 800 acre Welsh Valley in the 1960s in order to provide a water reservoir for the English city of Liverpool. The bully-boy tactics of the English parliament which rushed through the reservoir’s mandate in spite of heavy Welsh opposition is a clear example of the way water can be a highly fraught and contestable subject when it is viewed as a resource. The creation of the Tryweryn reservoir, as it came to be called, wiped out the small, Welsh speaking, village of Capel Celyn, which was home to twelve farms, a local school, a post office, a chapel and a cemetery. The heavy handed actions of the English and the deliberate marginalization of Welsh protest lead to a rise in support for a burgeoning Welsh nationalist movement consolidated by the political party, Plaid Cymru. Pratt’s work takes its title from the Liverpool city’s deputy clerk, who in 1956 attempted to calm Welsh indignation with the comment, ‘well, whose water is it? After all, God provided it’. In 2005, the Liverpool city council issued an apology to the people of Wales, lamenting the insensitivity of their predecessors’ actions, but still, patronisingly insisting that the medical and educational advancements Liverpool has made because of the reservoir, ‘has been of real service to the people of Wales’.

Sam Hartnett’s photograph, Fort Lane captures a desolate urban scene. A trickling pipe spills a miniature waterfall onto a city street, made all the more farcical by the nature-scene illustration pencilled earlier onto the wall. Spilling out into the street as surplus water, this uncanny overrun also reminds us just how heavily regulated water is in the urban environment. Channelled and contained through a vast infrastructure of pump houses and underground piping, water flows throughout the city in a continually alert state. Ready to go at our convenience, we often take water for granted, so much so, that it seems almost nightmarish to have to conjure a distopic future where water scarcity would see us utilising even the dishevelled water flows Fort Lane documents. It also pays to bear in mind that such fugitive water sources, would also, be more than likely, regulated, not as it currently is by civic councils given over to “public” goodwill charters, but rather, by a nefarious group of private interests, much like New York City’s infamous “tea-waterman”. During the early 1800s these opportunistic heavies only too happily monopolised access to the less than ideal water bubbling up from the ‘collect pond’. Even though the New York Journal described the water quality of this reservoir as being little better than ‘common sewer water’, the ‘tea-watermen’ were still able to rake in $275,000 a year each, which is big money even by today’s standards.

Alan Lacan and Harold Grieves have collaborated together to present water samples taken from Christchurch rivers. Presented in the quasi-scientific guise of an enlarged slide, this small sample will precipitate over the course of the show to reveal the impurities and toxins that currently reside in Christchurch city’s rivers. Eschewing Christchurch’s more renowned rivers, the Avon and Heathcote, those picturesque standard bearers of the garden-city’s serpentine appeal, Lacan and Grieves have chosen to collect their water samples from Christchurch’s many smaller tributaries, like the St Albans’ stream. These tributaries are often overlooked waterways but are increasingly becoming the focus of local attention which has been instrumental in regenerating the health and vitality of these small but significant streams.

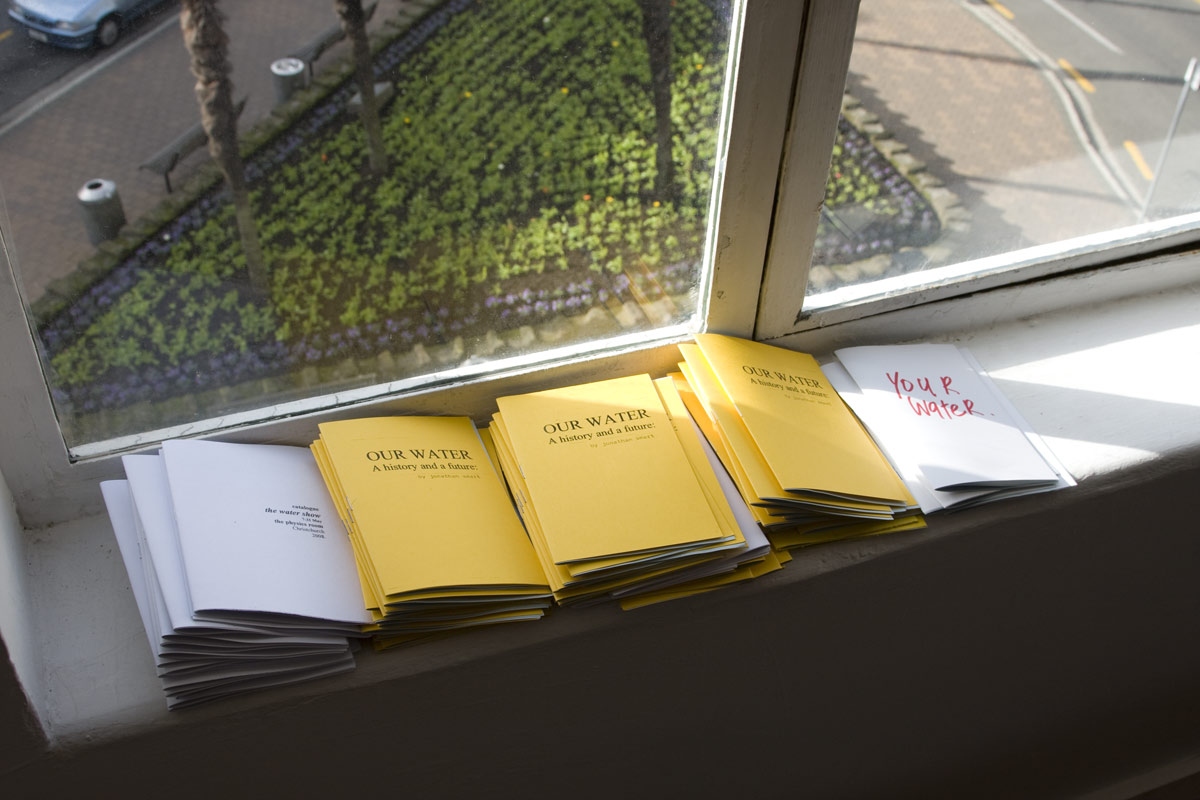

The Water Show also includes two written texts that explore the problematic aspect of treating water as a resource. A keen angler, Jonathan Smart’s text laments the decline in quality of our local rivers and attributes it to the wholesale conversion of south Canterbury into dairy-country. Harold Grieves’ text looks at examples of water policy in New York City and Athens in order to draw out some lessons for Christchurch. Focusing on urban water use, the text traces out the urgent need for a larger public dialogue about what is perhaps misleadingly dubbed our “public” water supply. The two texts are presented as monographic pamphlets and should be widely available, both in the gallery and the wider High Street area.