|

|||||||||

|

|

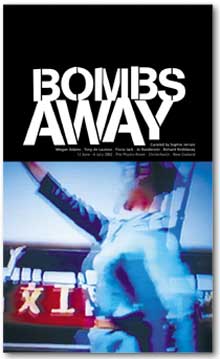

| ...GALLERY EXHIBITS 2002 | ...BOMBS AWAY | ||||||||||||||||||

|

Essay by David Lange It does no harm to wonder why people not unlike us should have chosen to shelter under the nuclear umbrella. Why do populations with which we have much in common allow their governments to build or deploy nuclear weapons, or actively seek the protection of powers which have nuclear weapons? It is on the face of it irrational to build an arsenal whose use would make the whole planet uninhabitable, to base a defence on a professed willingness to risk the lives of every last one of us, and to underpin international relationships with fear of the unthinkable. This is the essence of nuclear armament. For all its perversity, the necessity of nuclear weaponry is accepted, or argued, by many who are not otherwise out of touch with reality. Indeed, when New Zealand first adopted its nuclear free policy, the most common rebuke from the policy’s critics, both foreign and domestic, was that New Zealand’s exclusion of nuclear weapons from its territory was unrealistic. Its supposed idealism was the quality for which the nuclear free policy was most frequently faulted. This view was not the exclusive property of a political elite. Support for nuclear deterrence was, and is, common among people with whom many in New Zealand might easily identify. Many of us have close ties with the United Kingdom, a country in which the Labour party finally accepted that it could not win a general election until it abandoned its policy of unilateral nuclear disarmament. The Australian Labor party discarded its commitment to nuclear arms control after it came to office, and became the sternest critic of New Zealand’s policy. Exactly why people in the United Kingdom and Australia should support nuclear armament, or why voters in many democratic societies should allow their governments to spend countless billions arming themselves with weapons of mass destruction, is complex, but fear lies at the bottom of it. In the cold war era, fear was palpable in Europe. Nobody could escape the tension between the great power blocs. Fear that enemies might use nuclear weapons against civilian populations was genuine, whatever its source. Insecurity allowed, or perhaps demanded, an acceptance of the doctrines of nuclear deterrence. Although their use might be threatened, there was consolation in the assumption that the weapons might never be used. The risks of deterrence were lesser in this view than the risks of disarmament. There was far less immediate cause for fear in this country, but it was present nonetheless. There was considerable attachment to the ANZUS alliance, and some doubt that the nuclear free policy would prevail once it became clear that its price was the end of the active alliance relationship. While alliance membership was most often presented in political and diplomatic circles as a means of getting a hearing from the powerful and promoting our wider international interests, public support for the alliance was more visceral. It rested on the belief that New Zealand needed a powerful protector. This belief lost currency only gradually. Events in the 1980s saw the popularity of the nuclear free policy come to outweigh any lingering sense of insecurity. The end of the cold war put an end to much of the fear which had shaped international relations. The nuclear powers were accordingly able to reduce their stockpiles of nuclear weapons and limit their deployment. But nuclear deterrence is far from abandoned. It is still the foundation of military strategy among the nuclear powers. There remain active deployments of nuclear weapons. Nuclear weapons are not routinely deployed on surface vessels, but the right to deploy them is reserved. Strategic doctrines allow for the first use of nuclear weapons or for their use against countries not themselves armed with nuclear weapons. Technological refinement of weapons and weapons systems continues. In a climate where the need to openly threaten the use of nuclear weapons has diminished, their possession is more easily tolerated. There seems, for the time being, small chance of their use. They are seen as insurance against some unspecified future risk. Recent interest in New Zealand in reviving a form of active alliance with the United States feeds on something of this complacency. Because nuclear deterrence is no longer obtrusive, the nuclear free policy may be presented as something of purely symbolic value which could usefully be traded off in exchange for the benefits of a closer relationship with the United States. The advantages of such a closer relationship are rightly a matter for debate, but there is no doubting the price, as a recent episode confirms. New Zealand is still formally, if not actively, allied with the United States. It responded to the terrible events of September 11 with uncalculated sympathy. It sent members of its armed forces into danger in support of the war against terrorism. For all of that we are allowed the overweening condescension of being not an ally but a "very very very good friend". Much foreign policy debate in the future will revolve around whether there is more we can, or should do, in exchange for a different form of words, and what such words might actually be worth. New Zealand’s commitment to its nuclear free policy was tested in many ways in the 1980s, but we were to a great extent distant from the insecurity which led others to embrace nuclear deterrence. We are not in the same way immune from the complacency which allows many to believe that nuclear weapons are no longer a danger simply because their use is no longer openly threatened. The weapons are still with us, and there are still those who justify their presence. Complacency and indifference may in the end prove a greater threat than insecurity to the nuclear free policy. David Lange This essay originally appeared in Centre of Land Use Information Centre Essays Living without the bomb by Sophie Jerram

|

||||||||||||||||||