|

|||||||||

|

|

| ...GALLERY EXHIBITS 2002 | ...LIVING WITHOUT THE BOMB | |||||||||||||||||

|

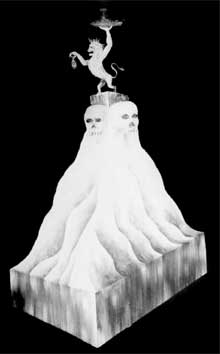

Essay by Sophie Jerram "The war started when people accepted the idiotic principle that peace could be maintained by arranging to defend themselves with weapons they couldn’t possibly use without committing suicide". So says British scientist Julian Osborne (played by Fred Astaire), when asked to explain how the entire population of the Northern Hemisphere has been annihilated in On the Beach, the film based on the anti-nuclear novel by Neville Shute. On the Beach was made in 1959. Nuclear deterrence was to be used by the five original nuclear nations as a legitimate explanation for the proliferation of nuclear weapons for at least another thirty years. And peace was maintained. We no longer live at ‘five minutes to midnight’, discussing with our neighbours the best ways to dig our private fall-out shelters. Deterrence, we could say, has been successful. When On the Beach was made, the prevailing thought was that after a nuclear war, fall-out or radiation clouds would inevitably make their way around the world and expose any survivors to such toxic levels of radiation that no-one would be able to live. A complete apocalypse. This too, has been shown to be mistaken. Humans are immensely adaptable, and can survive and breed under trying conditions. Exposure to high levels of radiation will affect a person’s genetic makeup, and that of their children, but it will not necessarily kill. Public perceptions of the effects of war and weaponry are imminently malleable. We perceive current evidence to conveniently fit our existing ideologies, whether they are the pro or anti-nuclear cause. The French urban architect, political theorist and peace strategist, Paul Virilio wrote at the close of the Cold War: "the history of battle is primarily the history of radically changing fields of perception. In other words, war consists not so much in scoring territorial, economic or other material victories as in appropriating the ‘immateriality’ of perceptual fields". This is particularly true of the Cold War, where the development of new weapons by the US or Russia was never revealed or proven, but always suggested. New technologies were constantly invented and the old, improved to defeat the imagined and real arsenal of the enemy. Following September 11, the enemy for the US has become the potential enemy. Frank Gaffney, a member of the US Center for Security Policy, recently defended the US’ leaked announcement that it would be willing to use nuclear weapons against a number of countries: "It’s a plan for reversing some of the disconnects that the Clinton administration adopted...This is an approach which says, ‘We’re going to think about the kinds of weapons we might need to use. We don’t want to. We hope we won’t have to, but we’re going to think seriously about what might be involved, and we’re going to make sure that we’ve got those - that they’re ready, that they’re reliable, that they’re safe and that the infrastructure to make sure all that’s possible is in place as well’". Of the five original nuclear nations, the United States’ nuclear strategy continues to be the most prominent and widely debated. As the world’s only remaining superpower, the United States’ continued development of ‘tactical’ nuclear weapons and its planned missile defence system sets a dangerous example to nations desiring to increase their own military power. Yet the United States’ criticism of other countries’ desires to test and use nuclear weapons is a ‘do as I say, not as I do’ approach. There are many contradictions in the U.S.’s portrayal of its weapons program, evident in the testing film used as raw material for Bombs Away. It is worth repeating here that the films used in Bombs Away are testing films. They therefore allude only to the potential human devastation of the nuclear bomb, rather than to the absolute and real destruction of life as witnessed, for example in Japan in 1945. The testing film cannot be explicit; the films refer latently to the damage that atomic and hydrogen bombs might inflict. It is up to the viewers to extrapolate the damage that could be incurred by the bombs in a non-testing context. Testing Nuclear Weapons, the film made for the US Department of Energy in 1978 and updated in 1989, describes the United States’ underground nuclear testing program at the Nevada Test Site. It depicts the employees of the site as members of a considered and sensible scientific community. Its images are 25 years old, but it is the most recent US government film available to the public. It has an air of disclosure, and a friendly, everyday feel. The scientists at the base are shown integrating with the broader community in Las Vegas; and the explanations of the images are set to normalise the activity of the site. The emphasis of the video is on safety measures employed at the testing site; the tone of the video’s narrator is moderate and reasonable. America as pioneer, pushing the boundaries of science, progressing consumerism for the sake of world peace - these impressions of the superpower are seductive and well practised. And the ‘reasonable American’ has pre-packaged answers at hand for any objection to war and the proliferation of nuclear weaponry. Fiona Jack’s Miasma series consist of large digitised images of billowing grey clouds. They are beautiful, glossy smokescreens, abstracted and ostensibly benign - until we understand that they have been created by the combination of toxic chemicals. The apparent safety of nuclear testing is belied by the vapours in these works- gases that creep insidiously and cannot be contained. Over the past five years, Jack’s work has moved from the appropriation of American-style advertising to a more abstract salute to the murky territories of commercial and governmental messaging. The grey vaporous masses in Miasma, like acid rain clouds threaten to seep into our minds and muddy our clear thoughts. Jack describes her dense childhood memories of the fear that paralysed her in her dreams: "I often had nightmares where my body would be falling apart and things around me were melting. These dreams were always monochrome, and it is the only time in my life I remember smelling in my dreams - a clean and sharp acid smell that makes me feel sick even now- 20 years later- if I smell something remotely similar. But the thing I remember being most scared of was this invisible gas that would attack my body. I imagined that nuclear war would be very quiet, and that I may not even know that it had happened; that things would just be overcome by this insidious gas." In contrast to the apparently candid American film, the 1962 Russian film Test of a Pure Hydrogen Bomb 50 Megatons in Capacity appeals to a Romantic, courageous spirit. The Russian film makers have no qualms about presenting an enchanting, visionary tale of the test of the largest nuclear bomb ever detonated - the ‘superbomb’, shot with Tarkovsky-style cinematography. It is by far the most beautiful of the atomic testing films, constructed in melodramatic shots and accompanied by a Romantic musical score. Three motifs recur: the isolated, wintry landscape, the impressive gleaming metal bombs under construction, and groups of uniformed officers standing around fuzzy maps of the Siberian peninsular, using rods to rap meaningfully at points here and there. Without knowing the film’s verity, these images could well be read as a spoof on the Russian spy film. It is this impression of the Russian and his map that Jo Randerson has chosen to embellish. Jo Randerson’s Untitled presents a view of an entombed Russian comrade, complete with bear, guidebook and vodka, seeking to place himself on the world map, a man yet to secure his place in the world. As an encased figure, behind a perspex box, he is now an object of curiosity, a thing of the past, no longer the hero of 19th and 20th Century wars but a displaced figure, alone and somewhat unsure of his responsibilities with the bomb. Randerson may or may not have been influenced by the travels of her mother, Jackie Randerson, who went to Russia in the early 1980s as part of a Christian peace mission. Jackie describes her own coming to terms with the Russian perspective on nuclear weaponry. The Russians ‘would rather have bombs than trousers’, and exhibited a simultaneous desire for peace, but also to never again experience the phenomenal loss of human life experience in the Second World War. In a recent solo theatre piece, Banging Cymbal, Clanging Gong, Jo Randerson has explored marginalised, aggressive identities. Jo Randerson plays a lonely Danish punk exploring the world in search of fellow rebels. Like the magpie in the work, Bird of Doom, the Russian in Untitled is depicted as a stateless bird, a politicised animal attempting to forge a new identity under the shadow of the post-nuclear age. Admiralty London: Plym, oblivion. Repeat, oblivion. Oblivion The last words of the UK film, This Little Ship, made in 1952, are a stark acknowledgment of the potential human destruction of the atomic bomb. But This Little Ship deflects the potential human consequences of the UK’s first nuclear detonation by focusing on the sacrifice of a ship, the HMS Plym, to the nuclear cause. "For now war is self destruction, and who will dare attack?" This pithy explanation of the penultimate line of the film of deterrence is in keeping with the poetic style in which the film is narrated. It is told by Jack Perkins as a ‘Boys Own’ story of drama and sacrifice. By allowing the viewer to get to know the HMS Plym before she is destroyed, our emotions are drawn to her loss, rather than to the impact of the bomb. This Little Ship is told with a heavy inevitability; as if the UK naval services are following an ordained path into doom. On a national level, this is pure deception: the UK was leading the development -it was the first country to make serious inroads into the feasibility of nuclear weapons, and established the "British Mission", a significant group of contributors to the Manhattan Project that developed the bomb dropped on Hiroshima in 1945. In Monument 2002, Tony de Lautour places his ubiquitous British lion atop a monument to death. The lion clutches a bomb in one hand whilst holding above his head the HMS Plym as one would hold a lamb to the altar. The base of the monument comprises sheer mountains embedded with skulls - this is a lion who has climbed over a lot of slippery slopes to get to the top. He is still proud, though, this lion, even as he threatens to be toppled by the size of the battleship or blown up by the bomb in his hand. Monument poses the question: Where are our monuments of today? Do we no longer construct them, hamstrung by our recognition that today’s heroes can be tomorrow’s villains? Monuments capture history in a form that books, paintings or films cannot - in permanent material and in public, they are hard to erase. In Monument, De Lautour’s lion is a foolish hero; his proudly thrusting chest a visual block to his precarious foothold. How long can he remain at the top of this pillar? Will his head be knocked off, his ship stolen by a marauding vandal? De Lautour reminds us that the ability of the British to embellish, to create heroic narratives, to make the horrific appear romantic, remains unsurpassed. Megan Adams, with Paul Redican, in Little Red Dance, has created a video capturing the refined, celebratory aspects of the Chinese army’s highly practised military exercises by creating a fictitious comrade who doubles as a cultural performer (dancer Liana Yew). They draw on the remarkably joyful, celebratory aspects of the highly elaborate preparations for the 1964 nuclear tests as shown in Mao’s Little Red Video of 1966. Of all the nuclear nations, probably the least is known about the Chinese nuclear programme, both in 1964 and now. In 1960, the Soviet Union cut aid to China, so the level of resource made available for the nuclear programme within China was unknown. The mystery surrounding its programme has sparked fear more recently in the West that China could be lending nuclear development support to other nations, and it is understood to have assisted Pakistan with its recent nuclear testing. Mao’s Little Red Video was made for internal use in China, procured by American Intelligence and a selective American translation dubbed over the top. We are told that the Chinese are determined to prove that they can do as well as the ‘imperialist’ nations. The pageantry of the military preparations are grand and impressive, and soldiers depicted as futuristic warriors pouring from their space suits gallons of sweat after an arduous trek around the desert. Cultural performances are used as ‘stimulating activities’ for the comrades at the nuclear test site. These cultural performances are as tightly practised as the army drills and scientific processes shown in the film; all in all, the socialist nation is presented as highly polished and disciplined. Of all the government atomic testing films, it is in this Chinese film that we see women taking an active role in the military work, and the commentary suggests pride in this equity. The character created by Adams represents both an emancipated female comrade and a replicable member of Mao’s army. She is available for sacrifice, but as a tightly trained comrade she would die, not as a rough pawn, but with beauty. In the ‘countdown’ sequence of the Little Red Dance, the comrade’s precise movements create the shapes of numerals, a gesture to the inevitability of human loss through the use of nuclear weaponry. Unlike the US, China and Russia, the French have consistently tested outside Mainland France, first in Algeria, then in the South Pacific. It is fitting, then, that Richard Reddaway’s wax coral works are growths found in spaces that art would not habitually reside. These are fascinating excretions, made from forcing one substance through another. Making the film of Nuclear Testing at Moruroa in 1995 as they broke the International Test Ban treaty signed only three years earlier, the French provide a coolly scientific explanation of their use of the coral atoll. We are to be reassured by the film’s animated images of the drilled core of rock that these explosions will not impact on the wider environment - save for a brief minute or two on the surface of the water. Reddaway’s No-one Believes They are Evil suggest otherwise - that it is not possible to contain such force without a ripple effect or movement elsewhere. The possibility of their action causing displacement is, to the French, apparently not worth considering. Like their attitude to the peoples in the Pacific, the French assume they can manoeuvre the physical environment without discernible impact. In one grand display of social and physical manipulation in Nuclear Testing at Moruroa, the French have assembled the ‘two to three thousand people who live and work on Moruroa...on the platform specifically designed to withstand the secondary effects of the shockwave’. Richard Reddaway’s brittle waxen works are, like the coral of the atoll, too unstable to maintain their form after exposure to huge climatic changes. Unlike coral, the wax works appear to spawn themselves, like fungus, glowing brightly amongst the unexpected debris of a gallery setting. These mutations are beautiful but oddly disturbing in their fluorescence. Like the French themselves, it is possible to be both charmed and frightened by them. If New Zealand were to make a film about nuclear testing, where would it be set? I would suggest that it should be set in the land of the ’80s - when fears of obliteration, nuclear winters and great masses of refugees from a nuclear war, ran rife. Where are these fears now? For some, the fear of the nuclear threat has been transferred to global warming, for some, to genetic modification, for others, to ‘rogue state’ terrorism. In interviews with New Zealanders concerning their memories of the nuclear threat of the 1980s, one aspect is common: the constancy of the imagery of the bomb and its effects. Tony Cairns, who co-wrote a book entitled New Zealand After a Nuclear War, says that "for the first 20 years of my life I was convinced that I was going to be destroyed by a nuclear bomb... I was dreaming from an early age of being followed by a very huge, Dinsdale-like bomb, about 500 foot long". Books such as his appear anachronistic in the post-Cold War era. But it was alongside images from films including The Day After and On the Beach, and documentary footage of the devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, that these books maintained a fear at the subconscious, as opposed to unconscious level, of the New Zealand public during the 1980s, and contributed to a galvanising of action - a rejection of nuclear weaponry. The international nuclear threat is perceived to have been diverted since the Cold War. In fact, the threat is ever more present as an increasing number of countries are either developing or purchasing nuclear arms. Their reasoning, that it is unfair for only five nations to keep the secret to the most powerful weapons yet known, when abolition has not yet commenced, seems reasonable. In a recent interview, Paul Virilio suggested that nuclear deterrence has been superseded by a second deterrence: "‘the information bomb’ associated with the new weaponry of information and communications technologies". He goes on to say "the age of the locally situated bomb such as the atomic bomb has passed. The atomic bomb provoked a specific accident. But the information bomb gives rise to the integral and globally constituted accident". I would argue that if this is a post-nuclear age; one in which the immediate threat of global destruction is no longer present, there are now multiple threats, particularly in the control of the content of our information and communications systems. As the imminent signing of a nuclear arms reduction treaty between the U.S. and Russia is heralded by the major press agencies, new weapons, including a ‘bunker busting’ nuclear penetrator are still being proposed by the U.S. Scepticism regarding the commodification of war imagery is not new. The effects of the media on war are well noted by writers including Baudrilliard, Noam Chomsky and Virilio: the twentieth century is regarded as having been the century in which war was re-defined to fit the television screens. However, what is being hidden from sight is as important to New Zealand as the framed pictures of war and attack. The invisibility of the potential consequences of nuclear attack poses a great risk to New Zealand’s stance opposing nuclear weapons. During the last fifteen years, the rise in economic power of New Zealand’s ex-ally, the United States, has been paralleled by the predominance of global newscasts controlled out of the United States. Unsurprisingly, this has resulted in our receiving little affirmation of New Zealand’s anti-nuclear pursuit. Whilst it is deemed of lesser strategic importance on the global newsdesks, it is harder to maintain it on the New Zealand news radar. But the threat remains, like Fiona Jack’s insidious gases, ever present. The need to manage our own imagery of this and other threats is paramount to our independence of position. This essay originally appeared in Centre of Land Use Information Centre Essays Bombs away by David Lange

|

|||||||||||||||||