|

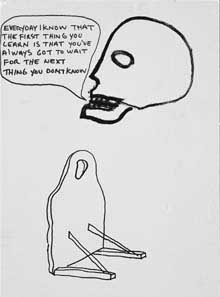

(an account of a convention illustrated with reproductions of works

by Adam Cullen, who, at the time of writing, was, to the best of my

knowledge, the most recent Australian artist to bother coming to New

Zealand . Besides,

his work is as good a summary of the impossible dreams and real nightmares

of Antipodean existence as any I can think of right now.)

|

|

Adam Cullen

Freedom has a double edge

1997 |

Adam Cullen

NEED TO FEEL TO TURN MY MIND OFF (detail)

1997 |

I have only been to Australia once so I don't really know much about

it. That trip was pretty much a complete disaster as research went-so

determined to leave

was I and thus escape my travel companion that I even didn't stay to see Link

Wray as embarrassing as that is to admit. This was probably due in no small part

to making the mistake of staying with Sydney filmmakers whose acclaimed work

led me to believe that the pointed saying "New Zealand short film: the new

pottery" might be extendable to material generated over there. And thinking

about what one might write for this Trans-Tasman issue was not made any easier

by a friend pointing out that Australians don't give a rat's ass about New Zealanders

anyway, confirming my suspicions that pursuing a compare-and-contrast model would

be futile. Because it appears to me that we are all in the same boat. Except

theirs is bigger with poisonous things in it, deserts and a slightly different

gene.pool-more Mediterraneans, but equally large bodies of Anglo-Irish crimo-poverty

settlers and remittance men. And ours is shaped like a key-hole.

The talk of another friend, presently engaged in the time-honoured activity of

thesis building and openly fixated upon Charles Darwin among others (Hmmm...

Mrs Darwin? Mrs Billy Childish? Mrs Handsome Dick Manitoba? Oh yeah, yep, Jwayne

Kramer) was no doubt behind my temporary engagement with a piece of information

that tumbled out an otherwise uninspiring paper at the recent Culture shocks:

the future of culture conference at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

in Wellington. Having been read excerpts from On the Origin of Species by

Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the

Struggle for Life (or "The

Origin" or "001" as she prefers to call it) detailing his experimentation

with ether and his belief in the virtue of lacking focus when developing theories,

my ears pricked up to the sound of his name and the claim that Darwin once described

the South Pacific as "the crucible of the theory of evolution".

Darwin itself as a place sounds like it has been positively struck down by a

vengeful god, a searing heat rendering its earth to concrete and young flesh

to raisins as penance for the theory that in an inspired stroke destroyed most

human mystique. After him humans were no longer Sons of Adam and Daughters of

Eve (if we go by the C. S. Lewis model in which the South Pacific is a place

of noble Last Battles, scrimshaw and exotic dangers), but over-evolved chimps which

are not intrinsically good and have no master plan. He took his theory to its

natural conclusion, ie. humans being at a base level pretty horrible, and needing

to really try to be pleasant to get on especially

when they have no classy traditions to curb their rudeness, or mildness for that

matter.

Indeed, the Antipodes were characterised romantically in colonial times as the

only area left on the globe where conquests could still be made above a 40 degree

latitude. So, a penal colony and a nation of shop keepers were established where

men could be really cruel to each other, and women could chase after them with

tea-towels. These primal 'scapes were a stage set for hillbilly mythologies,

with their fire and brimstone, sirens, cyclopses, and country music-fueled passions.

The drunken childhoods of our cultures are by no means over. And furthermore,

I don't remember voting for the New Right, and I bet Australians don't either.

Although fascistic regimes seem strangely at home on the flat planes of the South

Island's bald eastern seaboard where the mountains loom in our peripheral vision

symbolising doom and keeping those anxiety levels up. Extremes of weather and

a flailing economy make for a hostile environment that must be forcing some sort

of hasty evolution in humans. Disturbingly we find our biggest settlements lemming-like

by the sea, mountain conquerors on our banknotes, while Ayers Rock has thoroughly

wormed its way into Australian mythology via their collective landscape psyche.

(Although, kindly, at six, after the close of every working day, this mind-set

is absolutely skirted around by the no-sweat bush setting and no-lingering-big-deals

domestic bliss vibe of Home and Away. Thank you Grundy, what a relief.)

Well, out of the ether and back to the conference. There was a good deal

of telling material re the human condition 'neath the Southern Cross. But

first, parenthetically,

this conference about culture was typically "university" in tone and

content. In being interested in worthy subjects (cf. TV, the suburbs-respectively

the confidant and breeding ground of most academics), it belied innaresting points

of existential tension both here and there like confusion about quality of life

and identity in our new world colonies. As some Wellington comedian recently

pointed out, "why send a probe to Mars? We don't even know what's going

on in Invercargill." Missing was the faultless sort of illogical smoke poetry

and no-knowledge knowledge of a lot of Australasians' sea-worthy Irish forebears

expressed in a coming-of-age tragicomedy by J. P. Donleavy thus: "Ah Master

Reginald, you've learned your first lesson in life. Unless you were better off

where you've been, you're always better off where you are. But no matter where

you've been or where you are, you'll never know if you'll be better off where

you are going."

So, first up there was a talk, a kind of Woodsy Allen stand-up affair, given

by a small young Brooklyn boy called Douglas Rushkoff, whose credentials included

being a friend of Timothy Leary and establishing Wired magazine. He originally

wanted to call his paper "Futurists suck" in reference to corporate

mystification of technology and the future, but the organisers wouldn't have

it on. Anyway, his "Coercive futures? Living for profit in a shareware universe?" didn't

add up. It all fell apart for me when, sitting ever so informally on the side

of the stage, he professed the following: "Just like in physics there is

no such thing as cold, only an absence of heat, in the world, there is nothing

but good." I found this humanistic outburst to be so irksome that I cornered

him during the reception that evening and needled him until he admitted that

he has to try really hard to stay positive and sublimate suicidal impulses. And

indeed it would not be difficult for him to stay positive given that he is on

a real conference junket, giving papers at least twice a month all over the globe.

After Wellington, he was going home to New York for a night, then was off to

Budapest.

However, there was a really interesting close to home bit when he raised the

subject of television programming. He set out to expose programmers as being

patsies to the corporations that seek to sell things to viewers. This is achieved

by transmitting material designed to wind up our anxiety levels-oh god I am ugly

I have no superannuation plan and the is bacteria growing all over me I think

I'll go make myself a sandwich and how's your drink?-so we feel compelled to

spend our way out of the hole we see ourselves in. We find ourselves in the humiliating

position of having fallen in love with television, not because it is really great,

but because it is more powerful and manipulative than we. More evidence (Oh boy

o boy do I want a piece of that...), it seems, of the truly pornographic baboon-esque

character of our species. Darwin's legacy was this piece of unwelcome information,

that we are each with our own brand of ugliness, wan, and a specialist in our

own concerns. Our culture has mutated forest fire swift out of our imbecilic

dog-in-a-suit desire for sophistication way past our species' natural psycho-emotional

adaptation.

Rushkoff then presented ADD (Attention Deficit Disorder) as an adaptation

to

a world where everything wants you to submit-"is it any wonder that children

do not want to pay attention these days? If you could get what was going on all

at once, it would be so painful you would pass out." More clout for the

theory that the insane might be the only ones who know what is going on in our

communities these days. His points made me mindful of the should-be dictum "To

pay attention is to pay attention a lot" ,

not to mention the vast illicit use of Ritalin. (This ADD medication works to

calm down and supposedly focus children. But after adolescence it works on adults

like speed, only cheaper, and made available by parents selling off their kid's

scripts to the growing market for gutter drugs. According to recent statistical

hearsay, 80% of Australians are presently self.medicating in one form or another.

Hardly surprising when you consider that the flat cities of Australasia-Christchurch,

Invercargill, Adelaide-have some of the highest rates of clinical depression

in the Western world. And our literacy rate is going to heck in a hand-basket.

Poverty might be a good thing if one were approaching the gates of heaven, but

goodness translates to nourishing if you are a ways down the food chain.)

Later came Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, a museum theorist from the NYU

faculty

of tourism with "Black box/white cube: the museum as technology"-truly

a woman with an immaculate grasp of the absurd, viz. her line, "Experience:

ubiquitous, and under-theorized." At this point I once again lamented the

no-show of the speaker I was most looking forward to-"new museology" theorist

Jonathan Friedman and his proposed paper "Indigenous struggles and the discrete

charm of the Bourgeoisie". I think that this sort of thing was exactly what

the conference needed because much of the material seemed anthropological rather

than based in first hand experience, ie. museum people, academics-a most un-motley

crew-trying to get to grips with subjects from the outside. The image I was left

with after this event was that of an elephant's graveyard. We seem to be entering

a new evolutionary phase whereby the theoretical environment is no longer nourishing

anthropological takes on culture. Our access to the raw materials of human interests

has been made so easy via the mass media that we simply do not need people's

second hand pseudo-definitive summaries of subjects. As anthropology ebbs, new

subjective studies flow, and so do the baby elephant's walk into currency.

There was a definite air of absurdity to the proceedings as speakers seemed

to be standing prissily apart from life/ normal things. Like John Nixon

telling

Adam Cullen that "the difference between my art and your art is that mine

is neat and yours is messy." I

must admit that when studying culture, I too prefer to see what I am eating.

Or again in the words of Richard Meltzer "If only you could recapture the

times when you were just a creep and your responses to other creeps were just

as creepy, man that's were primal innocence is at." Today,

if the relevance of cultural studies is anything to go by, regressive is progressive.

Perhaps that would have made a really good souvenir T-shirt script for the convention.

Or better still might have been that characteristic call of the Antipodean mother

as she waits impatiently for the day her cubs leave the family burrow and fend

for themselves, "Cold? Well put a bloody jersey on then."

Gwynneth Porter

|

|