|

David Woodard, who has been featured in these pages

experimenting both with the disinhibiting powers of the Feraliminal

Lycanthropiser machine (Issue 8)

and the chthonic properties of ketamine (Issue 11), is, by profession,

a requiem composer and a DreamMachine fabricator.

More than a little preoccupied by what gives on the "other side",

Woodard has composed requiems for subjects as varied as a mutilated

heron and the victim of a cable car accident.

Woodard coined the term "prequiem" so that those in death’s

throes could hear his masterworks before they shuffled off this mortal coil.

Woodard’s latest and most publicized project to date involved composing

music to salve the soul of the Oklahoma Bomber, Timothy McVeigh. In the process

of organizing this unorthodox musical tribute, Woodard made contact with McVeigh,

though it is unlikely the mass-murderer ever got to hear the music composed

especially for his execution. Tessa Laird spoke to Woodard, a resident of Los

Angeles, just days after the execution took place.

Tessa: Could you describe the scene at Timothy McVeigh’s execution in

Terre Haute, Indiana, on 11 June, 2001? I have heard it referred to somewhat

cynically as "Bloodstock" and a "media circus". I never

saw any of the sordid TV coverage - I was cocooned by politically correct

public radio. However, I imagine that most Americans saw a very different picture.

Could you give an overview of the event itself from your own perspective, and

more specifically, the performance of your "prequiem" Ave Atque

Vale?

David: The word "Bloodstock" was invented by Tim’s former Terre

Haute death row cellblock-mate David Paul Hammer, whose prison diaries at one

time (in the months leading up to Tim’s execution) appeared on the Internet.

It is of course a play on Woodstock, the ’60s rock music festival which

shared with Tim’s execution the conspicuous presence of a vast "tent

city" and the spiritual function of a destination point for pilgrims.

In Tim’s case, the pilgrims primarily took the form of rabid media agents,

with an extremely scant sprinkling of concerned individuals. Woodstock, quite

conversely, was a pilgrimage of drugged-out hippies surrounded by a smattering

of entrepreneurial, fake-hippie media.

The Federal prison grounds are much larger than I had expected, having read

at www.bop.gov, the Federal Bureau of Prisons website, that they were merely

33 acres. Several football fields could easily fit into the front yard of the

prison, where I observed four cordoned areas under extremely tight security:

an area for protesters, who were bussed in from a designated meeting place

in a Terre Haute park at specific times; a death penalty supporter area, which

was separated by perhaps 200 yards from the protester area; an utterly massive,

sprawling media circus area; and what to me seemed the most dubious penned-in

field - the "media briefing" area, which served as the official

interface between the government and the media. All media representatives were

required to first attend a "media briefing" here before being issued

a media pass.

I was asked by the FOX network for an interview on Saturday morning. They sent

a "limo" (van) to my motel to collect me, as parking anywhere near

the prison was out of the question - due not to protesters and/or supporters,

both of whom were practically nonexistent, but rather the 1,700-strong media

presence. I was asked if I would first like to see the make-up lady, to which

I consented. After passing through security, and in that process personally

meeting Terre Haute Prison’s Public Affairs Officer Jim Cross, with whom

I had spoken on the telephone a number of times during my attempts to secure

use of prison grounds as a prequiem venue, I was carefully escorted to the

make-up trailer. The make-up artist was friendly, encouraging and from Indianapolis.

Next, a FOX producer, who was really just a kid, nervously brought me into

the media yard, initially keeping a watchful eye on my every move (it seemed

that perhaps Mr. Cross had identified me to the producer as a potential problem).

Only when I made fun of his paranoia (by remarking that he was making me self-conscious

about running and jumping over the three rows of 12-foot electric barbed-wire

fences) did the kid cool his heels and allow me to explore the media tent city

on my own. During my brief wandering, as I was snatched for an interview by

rival news company Reuters, I understood the FOX producer’s true concern.

The interview took place on a stage that FOX had erected along the media area

periphery closest to the prison buildings, which formed the backdrop. The FOX

anchor asked how it felt to have contributed to the lasting body of work that

will ultimately be attributed to Mr. McVeigh - as though Ave Atque

Vale and American Terrorist, the McVeigh biography, like Warhol

paintings conceived, created and screened with Warhol’s ‘signature’ by

anonymous Factory drones, are pyramids that may have been physically built

by slaves but were of course willed into being by Pharaoh McVeigh, cultural

institution. When I introduced the subject of the Wishing Machine, the radionic

device which had first compelled Attorney General John Ashcroft to seek McVeigh’s

execution with absolute determination, then compelled Tim to will Ave Atque

Vale through me and American Terrorist through Lou Michel and Dan

Herbeck, the FOX anchor swiftly concluded our otherwise nice interview.

Tessa: I’m not terribly familiar with the Wishing Machine’

David: A brief explanation occurs on my website: <http://davidwoodard.com/farewell2.html>.

Incidentally, I sold the model in question (i.e. the Wishing Machine used for

Tim McVeigh) to a young Texas man who was suffering from a malignant brain

tumor and given less than a year to live; he writes to me regularly, claiming

the machine caused his tumor to go into remission. A short story concerning

the device appears around p. 250 of William Burroughs’ novel The Western

Lands. When I complemented him on his story during a 1997 visit, William

introduced me to the machine itself. I was in the process of correcting his

improperly constructed model (i.e. replacing its cheap, low-conductivity aluminum

plates with copper ones) when he keeled over and croaked in August of the same

year.

Back to Ave Atque Vale. Forming an ensemble to play the piece was a

difficult task to complete within less than three days. Judge Richard Matsch’s

denial of McVeigh’s appeal (based on the FBI’s fraud against the

court) was announced on Wednesday; I departed Los Angeles on Thursday and arrived

in my motel room, which had been reserved by the Catholic Church, at midnight;

I awoke Friday morning with a Sunday evening Federal execution prequiem beckoning

before me in this claustrophobic town. First I marched into student-run amateur

radio station WISU’s studios to ascertain that they would indeed broadcast

the music, as promised by program director James Britt in May prior to the

initially scheduled date for Tim’s execution. The engineer now sitting

at the front desk appeared stunned and nervous by my presence, and proceeded

to tell me that Mr. Britt was no longer with the station. He had graduated

and was perhaps not even in town. I recalled Britt’s earlier explanation

to me over the phone, in which he said that the station’s Board of Trustees

was resolutely against participating in a McVeigh-hatched scheme until he offered

a compromise: just announce at a specific time (when Tim would be listening), "We

now interrupt our broadcast to play a special piece of music for a special

listener." According to Mr. Britt, the Board of Trustees had consented.

I began calling musicians. All prospects in this predominantly Bible Belt fundamentalist

territory overtly exhibited adverse knee-jerk reactions to the idea of being

involved in any way with McVeigh. Slowly my rhetoric evolved from (very early) "intended

to honor Tim McVeigh and the Holy Father’s request for his clemency," to "intended

to honor the sacredness of human life" (which seemed to immediately translate

as pro-McVeigh), to "intended to honor the sacredness of the death process," which

proved neutral-sounding enough to engage significant discourse.

On Saturday evening I attended a concert on the banks of the Wabash River given

by the Terre Haute Community Band, whose repertory included Sousa’s The

Star Spangled Banner and Gladiator March, as well as Grundman’s A

Scottish Rhapsody and even Ployhar’s Impressions of a Gaelic Air.

Impressed, and very relieved to be sitting in front of a real live brass section

on the eve of the scheduled prequiem, I enjoyed the concert and approached

the trumpet and trombone players afterwards - ready to employ my newly

evolved "intended to honor the sacredness of the death process" line

if necessary, which it certainly was. By the end of the night, through the

assistance of trumpet player John Penry, who also happens to be Treasurer of

the Terre Haute Federation of Musicians (the local musician’s union),

I had my brass sextet and a contract waiting to be signed - sure to deplete

the balance of my funds. I had convinced Penry to convince five other musicians

that Ave Atque Vale was a "neutral" piece of music, neither

in favor of nor against the death penalty. When apprised that this piece was

scored for not only two trumpets, two trombones, and tuba - but also cymbals,

Mr. Penry replied that it would be easy to find any dumb-dumb to play cymbals.

Indeed, the cymbals part merely accentuates cadential points - very intuitive

and simple.

Tessa: Perhaps you could talk a little bit about musical structure and influences,

so that those readers who are unfamiliar with your work might imagine what

it sounded like.

David: The first of the two sections of Ave Atque Vale, scored for strings,

winds and baritone soloist, was inspired by Sicilian composer Giacinto Scelsi’s Aion.

Due to time, financial and Bible Belt constraints, I was not privileged to

perform this primary section of the score on the eve of Tim’s execution.

I was, however, able to perform the slow and stately brass fanfare coda - which

was inspired by Wagnerian arias such as Liebestod and Magic Fire

Music, i.e. music intended to create tension that opens into greater and

greater tension and ever dashed expectations of resolve, ultimately for the

sake of a tremendous, otherworldly resolve.

On Sunday, June 10 at 6pm, my musicians (which included Terre Haute Community

Band’s conductor Glenna Gibbs, now in the capacity of trombonist) arrived

to meet me for rehearsal at St. Margaret Mary Church, about three miles from

the prison. Mr. Penry and another older man, trumpet player Vince Plank, looked

perturbed on arrival in the church parking lot. On the front lawn of the church

they could see protest materials. Soon the other musicians had all arrived,

sharing in visible expressions of distress. Pleased that they were at least

all appropriately attired in black, I attempted to look surprised myself - reiterating

that Ave Atque Vale is "politically neutral". However, among

their whispers with one another, the musicians had obviously divined the truer

truth of the matter: regardless of how "neutral" might be defined,

they would be accepting cash to honor the man they were determined to see executed.

Musician’s Union Treasurer and ensemble organizer Mr. Penry pulled me

aside to verbally express his dismay. "I really had to work hard at convincing

each of these musicians that your piece of music is in no way politically motivated." Mr.

Penry looked glum, as though he had been snookered. Frater Ron Ashmore had

kindly provided a large space for us to rehearse in - upstairs in a building

adjacent to the church. I found it odd that my "dumb-dumb" cymbalist

would turn out to be Mr. Penry.

As we launched into our single hour of rehearsal, I found that Mr. Penry was

not paying any attention whatsoever to my conducting. Moreover, he was playing

the cymbals several quarter notes off beat. I decided to devote my entire left

arm to him, demonstratively signaling each of his already painfully obvious

cymbal lines. Still, he would not play correctly. "Mr. Penry," I

eventually announced in front of the ensemble, "I am afraid we do not

have time to master the cymbal part tonight." Slowly, without looking

at me, he placed his cymbals down. "But I’ll pay you anyway."

At five minutes till 7, we slowly and quietly filed into the church, and the

musicians (except for Mr. Penry) assumed their seats below the cross. Frater

Ron introduced the prequiem, I ascended from my pew, and conducted the 3-1/2

minute brass fanfare coda from Ave Atque Vale. Afterwards, I returned

to my pew and watched as the musicians, quietly and somehow respectfully, collected

their music and filed out of the church. I then noticed that among the prequiem’s

listeners were Tim’s attorneys Rob Nigh and Chris Tridico, as well as American

Terrorist authors Lou Michel and Dan Herbeck. According to Frater Ron,

who took me out for chili later that night, the listenership included all of

the following morning’s execution witnesses.

Tessa: Do you think McVeigh ever got to hear his prequiem?

David: Attorney Rob Nigh had phoned me in my motel room on Sunday morning (the

day of the prequiem, one day before the execution). He was calling from the

prison on his cell phone. Tim had asked him if and when he would hear the prequiem.

I had to explain that WISU had chickened out. Our only avenue of broadcast

now was television news. Remarkably, Tim managed to secure a small b/w TV set

with basic cable for the prequiem night - a significant breach of death

chamber protocol. Fifteen to twenty news cameramen were present for the prequiem.

I have yet to ascertain whether Tim was able to catch a snippet on the evening

news. Even if he did, it would have merely been a snippet of the coda section

alone. To date (to my knowledge), no one has heard Ave Atque Vale in

its entirety - unless, of course, Pope John Paul II has secretly invited

an orchestra to convene in the Vatican City for a reading from the copy of

the score that is in His possession.

Tessa: Given you have stated you have a deep belief in the spirit world, why

should it matter to you whether or not Timothy McVeigh is executed? For that

matter, why create a prequiem if the spirits can hear the requiem? Are you

more concerned by your work’s reception in this world, or the spirit world?

David: Actually, I have considered performing Ave Atque Vale in its

complete form since the execution. Perhaps the work can be properly conveyed

to its intended subject, without having to rely on media cooperation, now that

Tim is beyond our illusory world.

Tessa Laird is afraid of dying which leads to some frighteningly

sensible behaviour. She carries out this rampant moderation in Los Angeles,

but hopes to return to New Zealand's excruciatingly safe shores in the

near future.

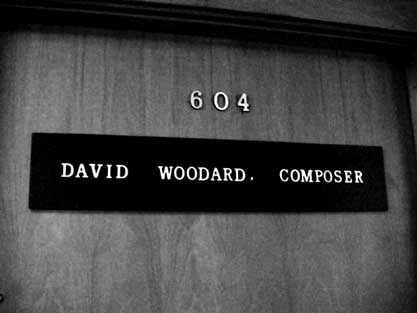

Composer David Woodard in his Downtown Los Angeles Office,

relaxing with his ermine-trimmed Dream Machine. Photographs courtesy

of Steve Shimada.

For further information on David Woodard, prequiems, Tim

McVeigh, or Dream Machines, try http://davidwoodard.com.

|

|