|

My first experience of the premiere Melbourne International Biennial

was lining up to get into the foyer of an office building in the CBD

for the opening party. The party had a nightclub feel and rocked for

a while until the bar ran out of beer at 11:30 and the party slowed down

with cheap white wine and champagne. I staggered out at 2am and though

the dancefloor had thinned out, the party was still going. My next encounter

with the MIB provoked hesitancy about the $18 entry fee into the exhibition

but eight floors of work by sixty artists required at least a second

visit and luckily the ticket was valid for three visits. The ex-Telecom

building - a partially gutted office building comprising rooms of various

sizes with a range of wall and floor surfaces and great views of the

CBD from its upper levels - was perfect for the installation and video

work of the Biennial's major exhibition, Signs of Life.

Unlike most Biennials, the MIB was notable for its lack of high profile international

artists, and with the exception of Louise Bourgeois and Robert Gober, most were

unknown here. In Signs of Life, local art was placed within a context

of wealthy developed countries - the United Kingdom, Northern Europe (particularly

Scandinavia), North America and Japan. Curator Juliana Engberg tapped into a

new version of humanism symptomatic of these rapidly digitising societies which

includes a melancholy brought on by a perceived distance from nature and from

authentic experience (and subsequent fetishisation of "the real"),

a return to the sublime, and the elevation of myth. For Engberg, art is a romantic

humanist quest, as she stated in the catalogue: "By its own complexity and

search for meaning among metaphors it delivers to us a synthesis of thought and

outcome that reflects our sense of humanity as we contemplate the reasons of

existence." But you didn't have to agree with her to enjoy the exhibition

- while Signs of Life evidently had a curatorial frame, it was loose enough

to allow for idiosyncratic meanderings.

|

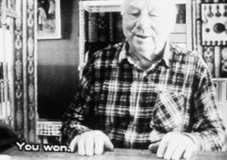

Gitte Villesen

Ludo 2

From the video Three Times Ludo

Courtesy Galleri Nicolai Wallner,

Copenhagen |

In its physical and conceptual layering, Signs of Life encouraged a range

of passageways and interconnections between the works but for me the sublime

thread offered the most intense experiences. A sense of wonder and mystery at

the limits of experience seemed to resonate through the exhibition, at times

accompanied by feelings of anxiety or fear, or by the pleasure of absolute alienation

or isolation. Mariele Neudecker's installation Unrecallable Now, for example,

a large diorama of jagged white landforms jutting out of a milky white ocean,

conveyed both a calm stillness and a sense of alienation that isolated the singularity

of the viewer. Also recalling the German romantic sublime tradition, Neudecker's

smaller work I Don't Know How I Resisted The Urge To Run consisted of

a glass box in a darkened room with trees submerged in slightly murky water.

A spotlight completed the scene, reminiscent of a misty forest lit by the last

rays of sunshine or a full moon, evoking a sense of mystery and suspense.

Engberg situated the sublime as a search for higher meaning or spirituality that

seemed nostalgic at times, as if trying to discover something lost, emphasising

in her catalogue essays psychological readings of the works that could bridge

the gap between reason and imagination/dream/vision. For me, the sublime in Signs

of Life was also where the ground gave way - literally, for example, in Cornelia

Parker's wall of chalk fragments entitled Edge of England: Chalk retrieved

from a cliff fall at Beachy Head, South Downs, England - leaving a fractured

sense of identity rather than a reconstructed whole. Following this fragmented

subjectivity, John Frankland's installation transformed a wall by adding a low

bench and a door painted in a clinical shiny gunmetal grey. While it appeared

functional and hinted at a possible depth behind the door, it also blocked access,

evoking both pleasurable desire and anxiety in this viewer. Here the sublime

was presented in a magnetic gesture towards the unknown, the impossible, the

indefinable where the mind cannot fully fuse reason and imagination.

Such alienation manifested itself in other works as a melancholic distance

from "nature".

As science and technology provide increasingly more efficient ways in which

to calculate and control the forces of nature, the greater the melancholic

feeling

of a lost relationship with nature. Patricia Piccinini's Plasticology provided

a sensory overload of constructed "nature". Comprising 51 TV sets with

images of trees blowing in a breeze (complete with amplified wind sounds), it

explored humanity's distance from romantic versions of "nature" and "authentic

experience". Meanwhile, Robert Gober's installation of an open suitcase

containing a drain grill, underneath which was a serene tidal pool complete with

seaweed and starfish, presented a deferred, poetic glimpse of nature through

the drain. Here, the "natural", the "authentically human" experience

remained teasingly or frustratingly just out of reach. In other works, the search

for authentic human experience came across more directly. Gitte Villesen's video

portrait of the eccentric man-next-door, Willy, exposing his all-too-human characteristics

such as his passion for Kamahl and Julio Iglesias and his eccentric obsession

with cars, provided a glimpse of an "authentic" human, seemingly

oblivious to mainstream cultural lifestyles and codes of behaviour.

With such a fragile grip on subjectivity exposed through sublime works, Engberg

also offered the affirmative solution of mythological works. The most powerful

of these for me was Robert Gligorov's poetic Bobe's Legend, a short video

piece in slow motion of the artist opening his mouth while a small white bird

flies out accompanied by a haunting oboe soundtrack. Myths make sense of our

environment, provide collective maps of meaning that are shared by a community,

and in this case Gligorov presented a poetic gesture that resonated with possibilities.

The artist giving birth to a bird which takes flight summed up what was for me

a poetic exhibition with moments of powerful intensity and an adventurous beginning

for the MIB.

D.J.Huppatz

Spring 1999

|

|